Three newly proposed call areas off the Oregon coast mean offshore wind could be a multistate affair in the West, requiring integrated planning and transmission, panelists said at Thursday’s annual meeting of the Energy Bar Association’s Western Chapter.

The U.S. Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) identified the Oregon call areas Thursday, shortly before the meeting. Last year, BOEM said it would offer leases in two offshore wind areas in Northern and Central California, the first offshore wind developments on the West Coast.

“The growing Pacific Coast scale of this, which has just been expanded [with that day’s BOEM announcement] … sets in motion a whole set of speculation about coordination across the region,” said Adam Stern, executive director of Offshore Wind California.

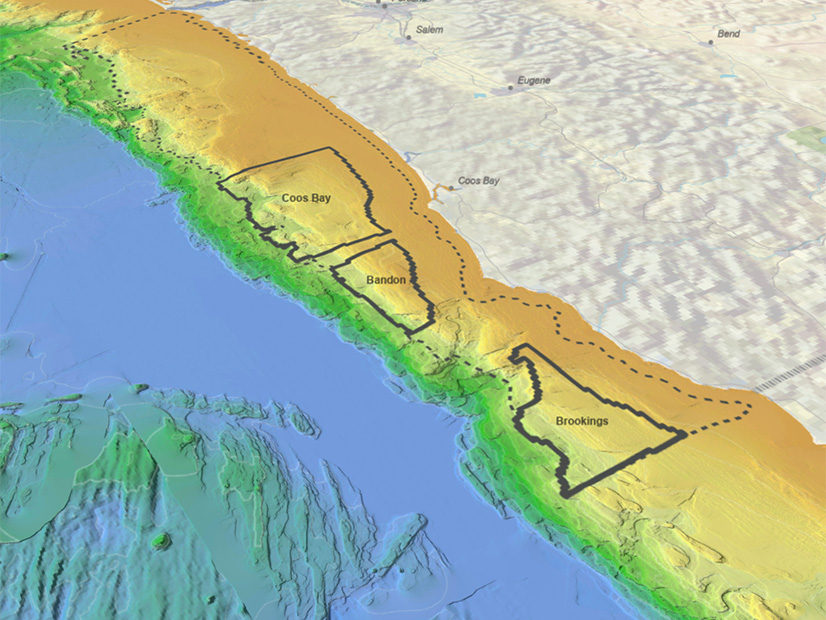

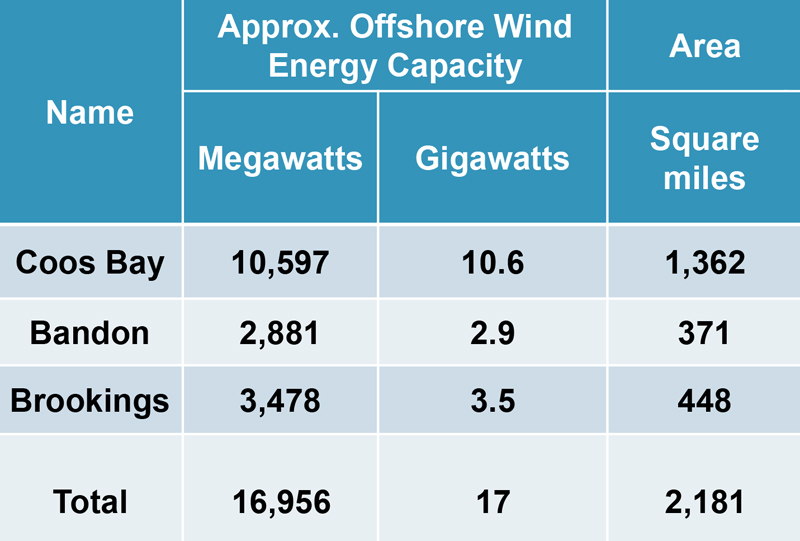

The three large areas off the coast of southern Oregon could support up to 17 GW of generating capacity total. BOEM said in a presentation last week it intends to consider 3 GW for “near-term commercial development.” The presentation, which first identified the proposed call areas, was published Thursday in preparation for Friday’s meeting of the BOEM Oregon Intergovernmental Renewable Energy Task Force.

Five study areas off California’s north and central coasts could potentially support 21 GW of offshore wind, according to a study published in 2020 by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL). BOEM ultimately decided to pursue commercial development of 4.6 GW: 3 GW in the Morro Bay Call Area off the Central California coast, and 1.6 GW in the Humboldt Call Area off the Northern California coast. (See BOEM to Offer Leases for Calif. Offshore Wind.)

Three newly identified call areas off the Southern Oregon Coast could eventually generate 17 GW. | BOEM

Three newly identified call areas off the Southern Oregon Coast could eventually generate 17 GW. | BOEMThe northernmost point of the Humboldt Call Area and the southern boundary of Oregon’s Brookings Call Area are about 60 miles apart.

An auction for the California’s first offshore wind leases is expected this fall, pending approval by the state Coastal Commission.

The auction will be like last week’s sale of six leases in the New York Bight, which drew competitive bids totaling nearly $4.4 billion. It was the “nation’s highest-grossing competitive offshore energy lease sale in history, including oil and gas leases,” the U.S. Interior Department said in a news release. (See related story, Fierce Bidding Pushes NY Bight Auction to $4.37 Billion.)

“These results are a major milestone towards achieving the Biden-Harris administration’s goal of reaching 30 GW of offshore wind energy by 2030,” the department said.

The New York auction’s high prices are potential harbingers of lease prices in California, EBA panelists said.

Ports Problematic

California, however, is different from the East Coast in several ways, including the need for more expensive floating wind turbines for its deeper waters and a lack of port infrastructure to build and support offshore wind farms, panelists noted.

“The ports are a huge issue in California,” said Ella Foley Gannon, a partner at law firm Morgan Lewis in San Francisco. “Our ports are not well situated to these wind areas.”

The NREL study found “distance to port” in California would be a major driver of construction, operation and maintenance costs for offshore wind farms. Major ports in Los Angeles, the San Francisco Bay Area and San Diego are either too distant, unsuitable or both.

Floating wind turbines can be assembled in port and towed to sea, saving time and money, but bridges in San Francisco and San Diego create obstacles, it noted. “The Golden Gate Bridge, for example, has an air draft limit of 67 meters, rendering all of the San Francisco Bay ports unsuitable for floating wind turbine assembly,” it said.

Expanding and improving lesser ports that are closer to the wind areas is one possibility, but that will require large upfront investments.

Theodore Paradise, executive vice president for strategy at Anbaric, a developer of offshore transmission, said the West Coast will need infrastructure more like the East Coast’s to attract top-dollar bids.

“I think part of what we’re seeing in the New York Bight today is a tipping point around confidence over infrastructure,” Paradise said.

The East Coast had public-private partnerships emerge to develop port facilities, he said.

New Jersey is building the New Jersey Wind Port, which can serve the New York Bight and other East Coast wind development areas. The state appropriated $400 million for the first phase of the project, including channel dredging and establishing marshalling and manufacturing sites. Private companies such as Siemens Gamesa Renewable Energy have applied to be tenants.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom’s fiscal year 2023 budget includes $45 million for port development, but far more will be needed, panelists said. The $1.2 trillion infrastructure bill signed by President Biden in November contains $17 billion for port upgrades, some of which could go toward development for offshore wind, they said.

‘Planning Big’

Another factor is transmission, which is more cost-effective when built to encompass larger offshore wind areas, they said. In Germany and the Netherlands, projects are being planned on a large scale with 2-GW cables, they said.

Early experience with smaller East Coast projects created a “spaghetti of cables across the ocean floor,” costing far more to develop and more per megawatt, Paradise said. California and Oregon could learn from that experience and develop state or regional transmission plans, he said.

He likened offshore transmission to the Texas Competitive Renewable Energy Zones transmission project, which transports wind energy from West Texas and the Texas Panhandle to population centers in the eastern part of the state.

CAISO recently included offshore wind in its inaugural 20-year transmission plan, a positive step, panelists said. The ISO said the state needs approximately $8 billion for 500-kV and HVDC lines to carry 7 to 13 GW of offshore wind to major urban areas. (See CAISO Sees $30B Need for Tx Development.)

“I think a key thing is planning big and planning for scale,” OSW California’s Stern said. “We need to achieve a state-based supply chain in order for this to create the jobs and other benefits associated with offshore wind. And that’s only going to happen if there are high targets and there is a supporting infrastructure investment that the state of California can make in its ports, in its grid and in some of the other resources that will be needed to make this possible.”