Government mandates are the best policy lever for supporting the world’s energy companies in what Shell CEO Ben van Beurden sees as an uphill climb to net-zero emissions.

“We cannot outperform 100 years of innovation in petroleum-based products in a few years’ time,” van Beurden said Wednesday at the 2022 International Energy Agency Ministerial in Paris.

Shell’s (NYSE:SHEL) biggest challenge in reaching net zero is addressing emissions at the point of energy use, and the only way to do that is “by offering different products,” he said. “If we are going to change the nature of the products that we sell, we need to have different policies encouraging the use of those products.”

The fastest pathway to product innovation and affordability is to mandate product use within target sectors, according to van Beurden.

“Sustainable aviation fuels are three times as expensive as petroleum-based aviation fuels, so we cannot make them economically relevant for airlines,” he said. “If you have a mandate to put 5% in the mix, then it doesn’t really matter what it costs, it just needs to be delivered.”

Customers are most often focused on the lowest cost of energy, but as more sustainable fuels are delivered, he said, the cost of supply will decrease.

Every sector of the economy “will have a slightly different recipe to reduce their carbon intensity and to figure out the best set of policies to drive that decarbonization,” van Beurden said.

Kevin Gallagher, CEO of Australian oil and gas producer Santos, agreed with van Beurden during the IEA panel discussion on international cooperation, saying that energy companies can produce hydrogen, for example, but market demand must exist for it.

There is a “thirst and demand for fossil fuels” that is not decreasing, Gallagher said.

Even more critical, he said, is that energy companies have access to the significant capital investments needed for decarbonization. Government policies, such as carbon credits and tax incentives, can create a stable energy environment that encourages investment.

Australia’s focus on carbon credits, for example, has allowed Santos to enter the design phase of what Gallagher says could be one of the largest carbon capture and storage (CCS) projects in the world.

“We worked very hard with government over the last few years to get to the point where [CCS] projects can qualify to generate Australian carbon credit units,” he said. But international cooperation with Timor-Leste, he added, has been equally important in moving the project in the Timor Sea forward.

“It’s critically important for governments … to operationalize Article 6.2 of the Paris agreement so that we can get more of these investments,” he said. The article sets out the foundation for international cooperation on decarbonization policies, such as emissions trading schemes, and allows for the transfer of carbon credits between countries.

International Stage

Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm, serving as Ministerial chair, highlighted the panel session as a platform for countries to share ideas.

“My hope is that we can … illuminate ideas and spread the word on practical, actionable efforts that any one of us could take on to learn from one another,” she said.

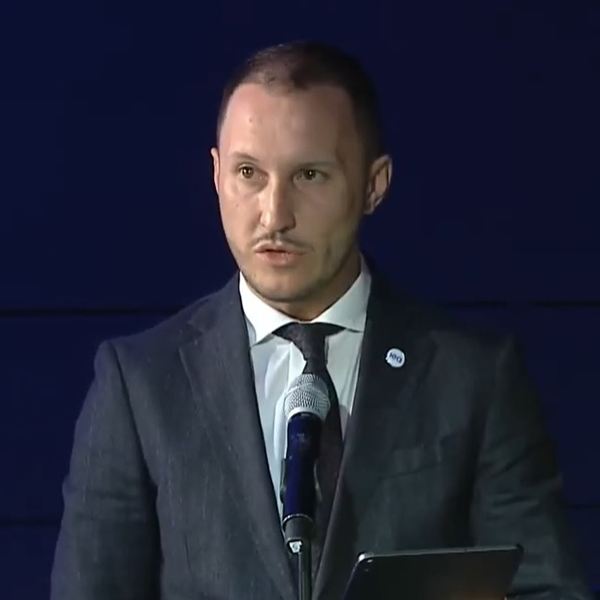

Yaroslav Demchenkov, Deputy Minister of Energy for European Integration for Ukraine, in Paris Wednesday | 2022 International Energy Agency

Yaroslav Demchenkov, Deputy Minister of Energy for European Integration for Ukraine, in Paris Wednesday | 2022 International Energy Agency

The panel paused to welcome Yaroslav Demchenkov, Ukrainian deputy minister of energy for European integration, who asked countries in attendance to “work together to integrate energy markets” and reduce dependence on Russian energy resources.

Russia’s war on Ukraine, he said, should be a catalyst to stop using Russian energy resources “as soon as possible, wherever possible.”

He also asked governments to restrict energy resources that are not easy to replace, substitute pipeline gas with other sources, such as hydrogen, and invest in balancing capacities, including storage.

“Commercialization of other types of green technology in the long run will guarantee energy independence and effectively contribute to the goal of the Paris agreement,” he said.