To reach carbon neutrality by 2045, California must more than double the amount of solar capacity built each year compared to its previous maximum build rate, according to modeling by the state’s Air Resources Board.

The build rate for battery storage would need to increase by more than six-fold to meet the 2045 target, the modeling found.

And reaching carbon neutrality a decade sooner, by 2035, could require the annual build rates for solar capacity and battery storage to increase more than three-fold and 10-fold or more, respectively.

The California Air Resources Board conducted the modeling as part of the process to develop the agency’s 2022 climate change scoping plan, a roadmap to meeting greenhouse gas reduction goals. Results of the modeling, which analyzed four scenarios for reaching carbon neutrality, were presented to the CARB board on Thursday.

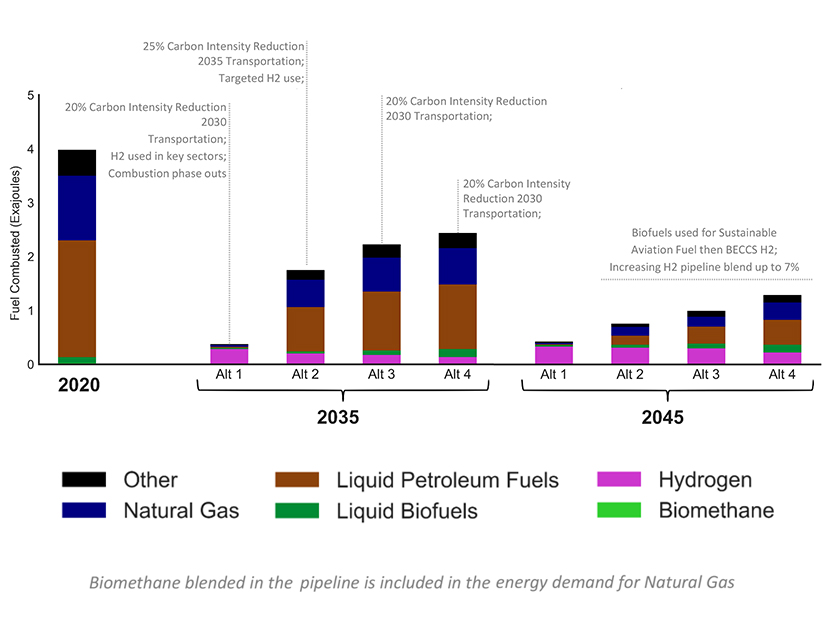

The first two alternatives would bring the state to carbon neutrality by 2035; the other two would reach the target in 2045.

Alternative one, the most aggressive of the four scenarios, would nearly eliminate fossil-fuel combustion by 2035. The scenario would require early retirement of gasoline- and diesel-powered vehicles: an estimated 16 million light-duty vehicles and 1.4 million medium- and heavy-duty vehicles by 2035.

Early retirement of natural gas appliances, such as space heaters, water heaters, clothes dryers, and ovens and stoves, would also be needed under the alternative.

The alternative would require “ambitious innovation in electric technology and aggressive consumer adoption trends,” Maureen Hand of CARB’s Industrial Strategies Division said.

Hand noted that a federal “cash for clunkers” program in 2009 cost $3 billion and removed about 690,000 fuel-inefficient vehicles from the roads.

Other alternatives would allow internal combustion vehicles and gas appliances to reach the end of their useful lives before their owners switch to electric models. The natural gas supply would be retained during the transition from gas to electric appliances.

The alternatives vary in their rate of zero-emission vehicle adoption and the extent to which they rely on carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) technology.

“Electrification is a cornerstone of each alternative,” Hand said. “The speed at which we need to expand zero-carbon electricity capacity is unprecedented.”

Hand said the most solar capacity that California has added in one year was 2.7 GW, and the largest annual increase in battery storage was 0.3 GW. Under the four alternatives, solar capacity must grow by 5 to 10 GW annually, and storage must increase by 2 to 5 GW per year, according to CARB’s modeling.

Role of Hydrogen

The alternatives envision an increased reliance on hydrogen as an alternative fuel in the transportation sector.

“The quantity of hydrogen needed in each of the alternatives to supply California’s projected demand is significant,” Hand said. “It will also need to be provided by low-carbon sources.”

One approach is to use electrolysis to split water into hydrogen and oxygen. If all the state’s demand is met by hydrogen produced through solar-powered electrolysis, solar capacity requirements would increase by 31 to 47 GW, according to the modeling. That’s about 40 to 50% of the state’s current electric generation capacity of 83 GW.

CARB board members listened to a presentation on the modeling on Thursday but took no action. One board member said the modeling showed the enormous cost of the 2035 scenarios.

“It would be hugely disruptive, hugely expensive to get to carbon neutrality by 2035,” said board member Daniel Sperling, who is also founding director of the Institute of Transportation Studies at the University of California, Davis. “Any kind of reasonable assessment would say 2040, 2045 is really the soonest we can get there.”

CARB is planning to hold workshops in coming weeks to focus on the economic and air quality modeling for the carbon-neutrality scenarios. The agency expects to present a draft scoping plan to the board in June and to finalize the plan by the end of the year.

Carbon Capture Controversy

All four scenarios analyzed in the modeling require some degree of carbon capture and sequestration for the industrial and refining sectors. Alternative one, in which petroleum refining would cease in 2035, would require less than 1 million metric tons (MMT) of CCS.

In the remaining three alternatives, the need for CCS would range from 8 to 11 MMT in 2035, dropping to 2.4 to 5 MMT in 2045.

Martha Dina Argüello, co-chair of CARB’s Environmental Justice Advisory Committee, urged the board to look at emerging evidence that calls into question the feasibility and viability of CCS strategies. The evidence comes from studies that are not funded directly or indirectly by the fossil fuel industry, she said.

“What happens if this technology doesn’t work?” Arguello said. “What happens if this technology, as [has] happened with others, actually ends up producing more carbon that it takes in?”

Arguello said CCS could also extend the life of the fossil-fuel infrastructure based in low-income communities and communities of color.

Rajinder Sahota, CARB’s deputy executive officer for climate change and research, said 20 years of testing has shown that CCS is safe and reliable.

Sahota said policymakers’ focus has traditionally been on ways to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. But the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change is now pointing to the need for CCS in addition to emission reductions to meet climate goals, she said.

“The science now says that has to be part of the solution,” Sahota said.