New Jersey’s Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) on Monday officially adopted new rules requiring more rigorous monitoring and reporting of greenhouse gas emissions in certain situations, while also releasing a proposal designed to limit new pollution in environmental justice areas.

The DEP posted in the New Jersey Register the final version of rules setting out a three-pronged approach for air pollution control that requires property and facilities owners to monitor and report emissions of methane and halogenated gases. The rules require facilities that emit 100 tons or more of methane a year — such as landfills, natural gas utilities and biogas generators — to report those emissions. Facilities that use 50 pounds or more of high global warming potential (GWP) refrigerants, which are used in refrigeration and air conditioning systems, must register and report their use of that equipment and refrigerants.

They also require public utilities that operate natural gas distribution lines in the state to report details of the lines, their advanced leak detection systems and blowdown events.

Through these measures, the DEP is addressing gaps in the department’s “comprehensive strategy to address greenhouse gas emissions” statewide, it said.

The rules levy penalties for companies that don’t comply of between $200 and $1,000 for a first offense and between $1,000 to $5,000 for the third offense, depending on the rule violated.

Preventing New Pollution

The initiative is part of Gov. Phil Murphy’s effort to cut emissions and set the state on a course of using 100% clean energy by 2050. His 2019 Energy Master Plan calls for the state by the same year to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to 80% below 2006 levels.

The master plan also sets out a multipronged approach to prevent new polluting plants and facilities from entering low- and moderate-income (LMI) communities and pave the way for those communities to enjoy the benefits of clean energy.

To that end, the DEP on Monday also published in the Register proposed rules that would allow the agency to block new facilities or mitigate the effects of expanding existing facilities in LMI or minority areas. While the rules are focused on the impact of pollution on disadvantaged communities, they may also contribute to cutting GHGs. The rules, for example, seek to limit ground level ozone, which the U.S. Energy Information Administration considers a GHG.

“If you limit emissions of other air pollutants, you could also limit emissions of GHGs,” said Nicky Sheats, director of the Center for the Urban Environment and board chairman for the New Jersey Environmental Justice Alliance, which helped draft the rules. Still, he added, it’s possible that the law might not reduce emissions because it could just prevent the location of a new polluting plant in one area so that it could arise in a different area.

The rules would set out a multistep process through which the department can approve or deny an application for a new pollution-generating plant or facility, or the expansion of an existing facility based on an assessment of both existing environmental conditions and how much the proposed facility would worsen those conditions.

DEP officials say the rules, which would provide the operating framework for the state’s Environmental Justice Law passed in 2020, would enable them to end the pattern that has long resulted in LMI and minority communities receiving a disproportionately number of polluting industrial, commercial, and government plants and facilities.

The department plans to hold four public hearings in July on the proposal, and to have the rules in place by year-end.

“This law is transformative, literally the most transformative law in at least 30 years,” DEP Commissioner Shawn LaTourette told reporters at a press briefing on the rules June 2.

The rules would require the department to analyze and evaluate permit applications for eight categories of proposed pollution generating plants and facilities: major sources of pollution, such as power plants and cogeneration facilities; incinerators or resource recovery facilities; large sewage treatment plants; transfer stations or solid waste facilities; recycling facilities that receive at least 100 tons of recyclables; scrap metal facilities; landfills; and medical waste incinerators.

They would also give the DEP the authority to take steps to prevent or limit the placement of additional polluting facilities in disadvantaged communities, which state officials account for about half the state’s population.

“We have never had that level of authority before, to look at an entire facility’s emissions; that [did] not exist,” he said. “Now it does,” he added, and said: “There are many things that happen at a facility that cause negative environmental outcomes, that we don’t have an existing hook into that these rules now finally gives us.”

Conflicting Visions

Environmentalists welcomed the proposal.

Sheats said he believes few, if any, other states have a law as tough as New Jersey’s. The key element is the DEP’s ability under the rules to do a cumulative impact analysis of a proposed facility, studying not just the environmental impact of the proposal but the ongoing impact of all the polluting facilities placed in the area in the past, he said.

“It covers multiple sources of pollution, so multiple pollutants,” he said, adding that the rules would also give the DEP the right, when making a permitting decision, to look at “social vulnerabilities” such as disease rates and the lack of health care in the community.

Maria Lopez-Nuñez, director of environmental justice and community development at Ironbound Community Corp. in Newark, expressed the hope that they will help halt the stream of polluting facilities into her neighborhood.

“We’ve been waiting a long time for the type of protections that these rules lay out,” said Lopez-Nuñez, adding that there although the rules could still be improved, they are a good start.

“Prevention is the best tactic,” and the EJ Law helps do that, she said. “We want to make sure that the industry that comes into the neighborhood is the greenest and has the best technology, or that it doesn’t come here at all if it’s going to contribute to the problem.”

But the New Jersey Business & Industry Association, one of the state’s largest trade groups, said the proposal did not address some of the organization’s concerns with the law, especially the broad sweep of its reach.

“While we understand that more needs to be done to address environmental conditions in many of our state’s disadvantaged communities, this rule covers too much of the state and sets up impossible standards to meet,” he said. “The result will be that no new major manufacturer can locate in these areas, and those that are already there will not be able to expand,” he said.

Evaluating Stress Factors

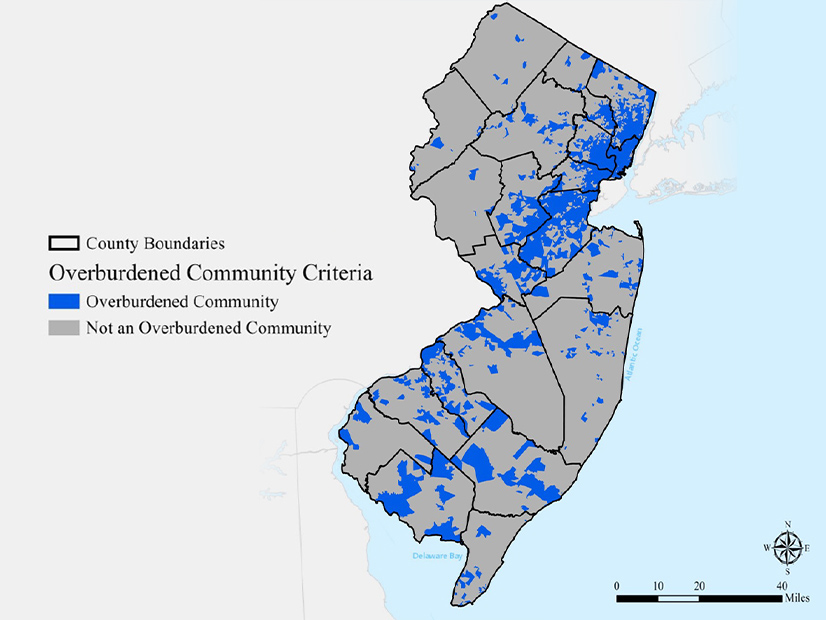

The rules would kick in when a permit application for such a facility is submitted to the DEP and require the department to analyze the community around it to determine whether it is “overburdened.” The proposal defines that as a census tract with one of three characteristics:

- at least 35% of households qualify as low-income;

- at least 40% of the residents are minorities; or

- at least 40% of households have limited English proficiency.

If the DEP concludes that the community is overburdened, the rules would then require the DEP to look at how the existing environment is shaped by 26 “stressors” or stress factors that can create adverse environmental conditions and if the proposed facility would increase the stress, and by how much. Among them are: the amount of ground level ozone; fine particulate matter; the cancer risk from diesel participate matter; traffic density and presence of railways in the area; the presence of known contaminated sites; and the amount of sewage overflows in the area. The factors also include more general contributors to health stress, such as the unemployment level, the portion of the older population that has less than a high school diploma and the lack of recreation space.

Disproportionate Impact

The results of that analysis would be compiled into an Environmental Justice Impact Statement and made public and scrutinized at public hearings, said Sean Moriarty, the DEP’s deputy commissioner for legal, regulatory and legislative affairs.

“The applicant will be required to respond to all public comments substantively,” he said. “They’ll be required to provide information or to provide measures to address the concerns of the community. And that will be part of the decision the department ultimately makes upon completion of that process.”

The DEP will then assess whether the facility will have a “disproportionate impact” in worsening the environmental burden, he said.

“For new facilities, we have the authority and are required to deny an application where disproportionate impact exists unless the facility can demonstrate that it serves a compelling public interest in the overburden community,” he said, adding that the benefits must be local, rather than presenting a compelling public interest statewide or in a broader area.

The DEP can’t deny the application if it calls for an expansion or renewal of an existing facility, he said. But in that scenario, it is “authorized to impose appropriate conditions” that would avoid or minimize the impact on the community, he said.