ATLANTIC CITY, N.J. — Spurred by the rapid rise in renewable energy project planning and declining battery costs, storage development is growing nationwide, but states need to ensure that they fund, shape and incentivize projects that contribute to their emission-reduction goals, a speaker told New Jersey’s Clean Energy Conference on Oct. 4.

States such as New Jersey, which is in the process of planning its first large-scale electricity storage incentive program, need to focus not only on stimulating storage capacity development but on making sure that the resulting projects help cut the use of fossil fuel generating plans, Todd Olinsky-Paul, of the Clean Energy States Alliance, said on a panel at the conference, organized by the New Jersey Board of Public Utilities (BPU).

The goal is “not just to get the storage there; it’s to get it there and link it to whatever policy targets or aspirations the state has,” Olinsky-Paul said. Projects need to charge up their batteries with cheaper, off-peak power and be ready and available to discharge when demand is greatest, to help negate the need for utilities to fire up fossil-fueled peaker plants, he said.

His comments came amid what he said is a dramatic increase in storage development in almost all states. Ten years ago, he said, he could have summed up national storage development activity by citing a handful of programs. “But things have exploded so much in policy in the last few years that I can no longer do that,” he said.

The rapid advance of the sector prompted another panelist, Brian Kauffman of Enel North America, to advise states looking to jumpstart or boost their storage capacity that they no longer need to think of developing a pilot program first.

“There’s a lot of examples of how to structure them and what results in customer uptake. There’s a very mature ecosystem of competitive purchase market participants,” Kauffman said.

“A lot of times, these pilot programs are set up where you don’t really know what the cost of doing the project is going to be [or] who’s going to participate in the project; you just want to learn,” he said. But now, “you have thousands of customers who are participating in programs across a dozen states or so.”

Finding the Right Incentive Level

Storage is widely seen as a paramount element needed to manage electricity supply as intermittent renewables become increasingly dominant.

The conference came just after New Jersey, admitting that it had lagged state ambitions in developing storage capacity, released a straw proposal on Sept. 27 that outlined a plan to stimulate the development of standalone storage capacity by offering incentives for grid-scale and consumer-level projects. (See NJ Offers Plan to Boost Lagging Storage Capacity.)

The BPU’s plan, known as the Storage Incentive Program (SIP), would provide incentives for both utility-scale and distributed projects. About 30% of the incentives would be paid to storage projects as fixed annual incentives, with a set value per kilowatt-hour of capacity. The remainder of the incentives would be paid through a “pay for performance” mechanism and tied to the environmental benefits.

Jim Ferris, deputy director division of clean energy at the BPU, told the conference that the fixed incentives would be awarded using a “declining block structure” that has worked in other states. The program would set capacity blocks at a certain incentive, and once the BPU has allocated a block of incentives to storage projects, a new block would open at a lower rate.

“In that way we are providing certainty to the market, but also finding the right incentive level,” Ferris said. “Obviously, if a particular block does not fill at that incentive level, we will have the opportunity to either extend that particular block and incentive or even go back and increase the incentive.”

The agency also has sought to ensure that it does not provide financial support for a project that “just sits unused,” he said. To receive the incentive, “the device will need to be available for 95% of hours,” he said.

The pay-for-performance incentive, which is based on PJM marginal carbon intensity data, is designed to tie the BPU’s incentive to demonstrable emissions reductions, Ferris said.

“So we would be incentivizing when storage is charged when emissions are low, and discharged when emissions are high. And that delta will yield an incentive,” he said. The performance incentive for distributed projects is based when the project injects energy into the system or is used to reduce the use of energy at the request of electric distribution companies, a strategy used in programs in Connecticut and Massachusetts, he said.

Monetizing Storage

States have taken different approaches in seeking to stimulate storage development, CESA’s Olinsky-Paul said. They include mandating a certain amount of storage by a particular date, or just setting a target capacity procurement, he said. Nine states have set a target. Among them are California, shooting for 1,825 MW by 2020; Massachusetts, with 1,000 MWh by 2025; New York, with 3,000 MW by 2030; and Oregon, 5 MWh by 2020.

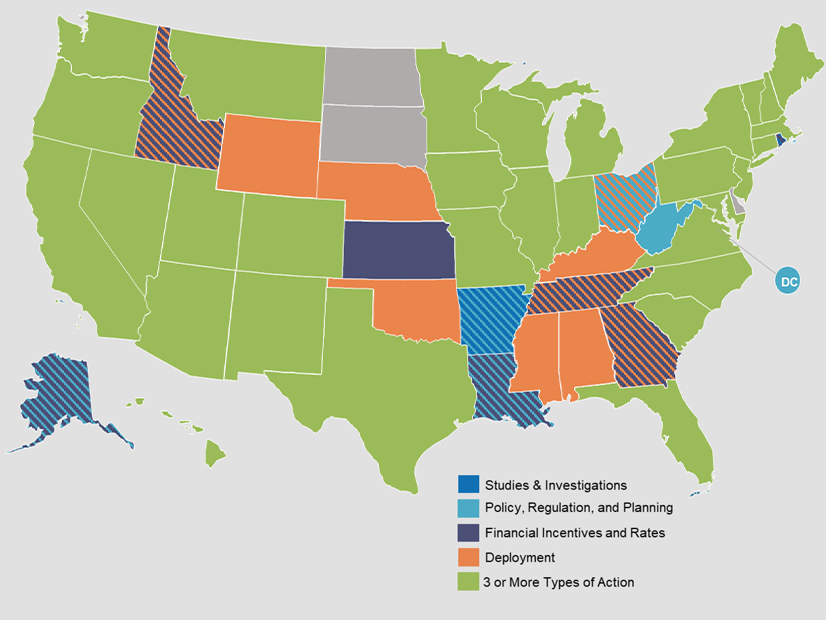

He displayed a slide that showed more than two dozen states have taken three or more types of action to plan for storage development, including studies and investigations, new policies and regulations, and financial incentives and rates. And all but three states have taken at least one step toward storage development.

One difficulty in stimulating storage development, according to the BPU and panelists at the conference, is that storage devices are difficult to “monetize,” which in turn puts the onus on state support. For that reason, the BPU proposal encourages investors in storage projects to pursue “value stacking,” or looking for several revenue streams to support the project.

While storage projects can provide benefits such as reduced electricity costs and emissions, “the current revenue streams, as in a lot of places in the U.S., including New Jersey, really aren’t sufficient now for storage to scale,” Enel’s Kauffman said.

Olinsky-Paul said one of the “best practices” that states should follow is identifying the attributes of a project that are “priced” or monetizable. He cited the example of a service station owner who installs a storage project on the property.

“So when the grid goes down, I’m able to fuel customers’ cars, first responder vehicles; that’s providing value to the community,” he said. “Did I get paid for it? No. Because there is no market for resilience. I can’t bid that service into a market or sell that service to utility as a backup power service.”

So the state needs to look at the balance of monetizable and non-monetizable benefits and work out “how are we going to provide that gap funding somehow to encourage that market to develop,” he said.

For the operator, the monetary benefits depends on the business model that the storage operators develops, Olinsky-Paul said. For example, the operator may use an arbitrage model of charging up the storage at night when the power price is low and selling the energy at peak hours when the price is higher, he said.

The operator of a solar farm may find storage provides “capacity value,” which in turn provides a financial revenue, he said.

“Solar by itself doesn’t have a lot of capacity value, because it doesn’t have an on-off switch; you can’t rely on it,” he said. “So you’ve now firmed the solar power that was previously variable. Well, there’s a value to that. If you’re bidding that power into a wholesale market, and they want firm power, they’re going to pay more for it if they know that you can turn it on and off than if you are just at the mercy of the clouds.”