Carbon capture and storage is having a banner year, with 30 commercial CCS facilities now in operation worldwide capable of storing more than 42 million tons of carbon dioxide per year. Add in a pipeline of 164 projects in various stages of development, and the potential stored capacity jumps to almost 244 million tons per year — a 46% jump over 2021 — according to the 2022 Status Report from the Global CCS Institute.

“After so many challenges and so many false starts … the momentum is palpable,” said Brad Crabtree, assistant secretary of the Department of Energy’s Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management.

But speaking at a webinar on the report Monday, Jarad Daniels, the institute’s CEO, said optimism about new momentum in the industry must be tempered by the need for unprecedented growth. “Global efforts to reduce emissions, including investment in CCS, are still grossly inadequate overall,” he said. “Government policy must be met with private capital to unlock the full potential of CCS and limit global warming to 1.5 degrees.”

Hitting that target will mean increasing carbon storage capacity more than 100-fold by 2050, said Guloren Turan, GCCSI’s general manager for advocacy and communications.

“The science shows that reaching our sheer climate goals is practically impossible without [CCS],” Daniels said. “CCS is a mature, well-understood technology that is increasingly commercially competitive across the full value chain from capture to storage.”

The report highlights major industry developments, with the expansion of the 45Q tax credit in the Inflation Reduction Act at the top of the list. Daniels said the new law’s $85/ton credit for CCS and up to $180/ton for direct air capture (DAC) could increase deployment 13-fold in the U.S.

Denmark’s €5 billion investment in CCS has also signaled a growing market in Europe, with the Orca DAC plant in Iceland now sequestering about 4,000 tons of CO2 per year. The plant uses a process called mineralization, which turns the injected gas into stone in about two years.

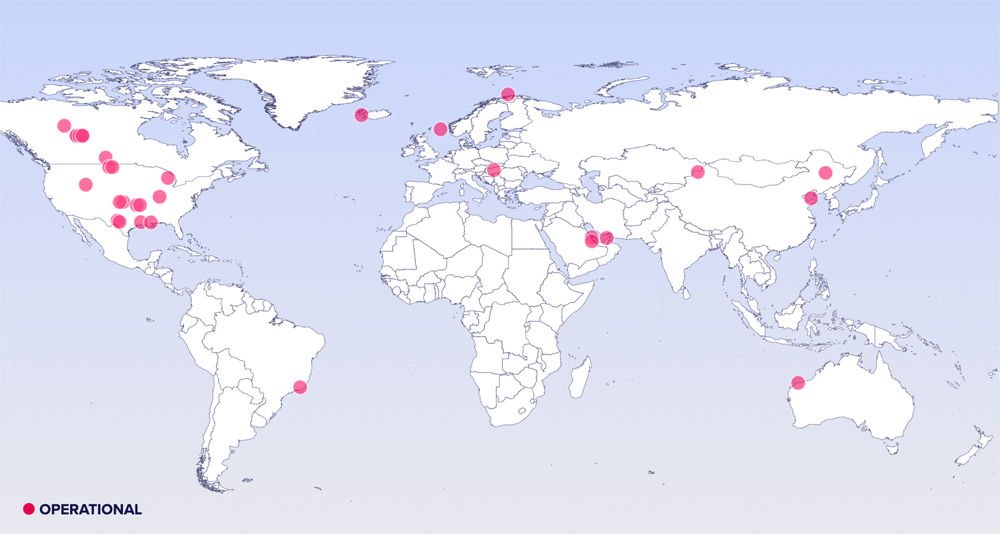

CCS plants worldwide now number 30, with 164 projects at various stages in the development pipeline. | GCCSI

CCS plants worldwide now number 30, with 164 projects at various stages in the development pipeline. | GCCSI

Climeworks, the company behind the plant, recently broke ground on an even larger direct air capture facility in Iceland, which could sequester up to 36,000 tons per year, according to the company.

China has also opened its first CCS plant, with the capacity to capture 1 million tons per year, which is being used for enhanced oil recovery (EOR), according to the report. A second plant, which will capture carbon from coal-fired generation, is under construction.

Despite such progress, the industry faces a challenge in winning over the sizeable number of CCS skeptics, said U.K. and U.S. energy officials speaking at the event. In the U.S. and elsewhere, environmental and other community groups have criticized the technology as a too-expensive strategy for extending fossil fuel generation.

“Not everyone supports carbon capture as the route to net zero,” said Alex Milward, director of carbon capture utilization and storage at the U.K. Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy. “It’s important for us all to work together to bring everyone along on this journey as well as we can.

“There’s more we all need to do together on international standards and modularization and product standards and transport standards, and then we [need] to get the optimal balance between where world CO2 is emitted and where we can cost-effectively capture and store it,” Milward said.

“We need to get implementation right,” agreed DOE’s Crabtree. “There’s a lot of misunderstanding about what [CCS] technologies can and cannot do, but there are also real legitimate concerns about how these investments will benefit in real tangible ways communities, economically and environmentally. That’s something we really have to focus on going forward.”

Turning Point

A turning point for CCS, besides the IRA, was its recognition by organizations such as the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and the International Energy Agency as critical to the 1.5-degree global climate goal.

In line with that institutional validation, a core driver for market growth is “the demand for greenhouse gas emission reductions in line with net-zero commitments from governments and businesses, together with rising expectations from civil society,” Turan said.

Other factors include the need to decarbonize “products that are critical to human economic development,” such as steel, cement and chemicals, she said.

Early development has been focused on EOR, the injection of CO2 to produce more oil from low-producing wells, which accounts for 21 of the 30 facilities currently in operation. Turan expects the project pipeline will be more focused on other forms of sequestration.

The U.S. currently leads the world both in operating CCS facilities and in projects in development, according to the GCCSI report, with the IRA and $12 billion for direct air capture hubs in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, focusing on development and investment.

DOE issued a notice of intent for the funding in May, and according to the agency website, an application opening date is expected by year-end.

In addition, the report notes other key policy advances, with the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Administration releasing new guidelines on CO2 pipeline safety and the Bureau of Land Management issuing guidance on CO2 storage on public lands.

“One of the exciting things for us, it’s not just the scale of these resources [in the IRA and IIJA], it’s also for the first time, we’ve really expanded research and development to include large-scale commercial demonstration, and that’s a major policy change in the United States. It’s long overdue and needed to really ramp up deployment of carbon management technologies across the economy.”

Other key funding in the IIJA includes $2.5 billion for “the development of dedicated regional geologic storage sites” and $2.1 billion for “carbon dioxide transportation infrastructure finance,” Crabtree said. The two projects will work in tandem, he said, so that “we can finally get beyond this historic chicken-and-egg challenge where you develop a carbon capture project, but how do you get the transport done, who develops the storage site?”

The goal, he said, is to build out a CCS “ecosystem in an integrated way on a regional basis, importantly to reduce costs and ultimately so we can bring carbon management to climate scale.”