The U.S. will need up to 58,000 full-time workers to meet the Biden administration’s goal of building 30 GW of offshore wind by 2030, according to a new study by the Department of Energy’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL).

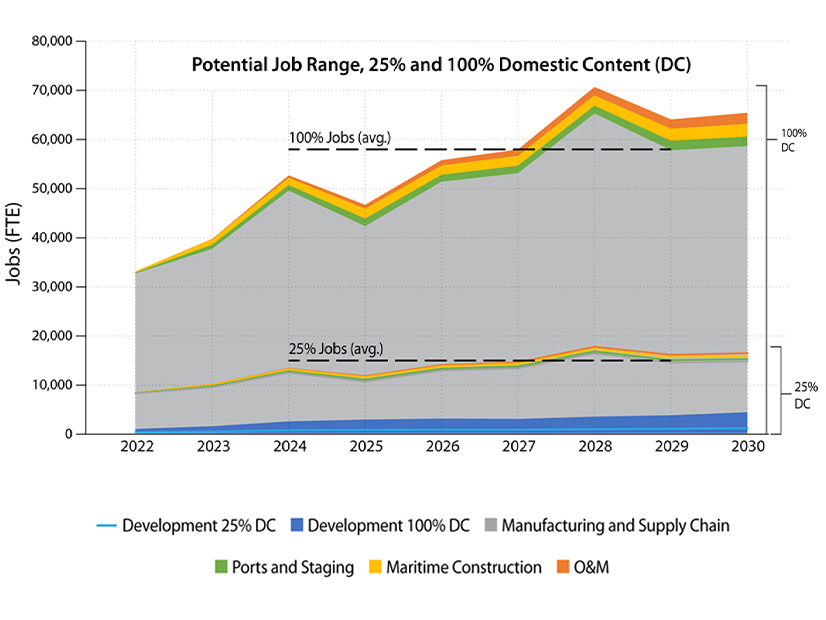

Released Tuesday, the study estimates that reaching the 30-GW goal will require creation of between 15,000 and 58,000 full-time equivalent positions between 2024 and 2030, based on assumptions of 25% and 100% U.S.-made content in the offshore installations, respectively. The industry currently employs fewer than 1,000 workers, DOE estimates.

“The offshore wind energy industry could provide tens of thousands of good-quality clean energy jobs for Americans over the next decade,” Alejandro Moreno, DOE’s acting assistant secretary for energy efficiency and renewable energy, said in a statement accompanying the report. “With this study’s comprehensive findings, we can capitalize on this opportunity and grow a strong domestic workforce for the burgeoning offshore wind energy industry.”

NREL said its estimates include only “the direct and indirect offshore wind jobs associated with development, manufacturing, installation and operation of offshore wind energy plants,” and not additional jobs that could be created in communities supported by offshore development.

The study’s authors said they modeled their scenarios by “assuming a deployment pipeline of awarded, soon-to-be-awarded and anticipated lease areas for fixed-bottom and floating offshore wind projects sufficient to reach 30 GW by 2030,” which were detailed in another NREL report released earlier this year. Fixed-bottom capacity was assumed to be installed on the East Coast, and floating capacity was assumed for the deep waters along the West Coast.

NREL expects the industry to rely on a relatively small domestic workforce for offshore wind farms installed between 2022 and 2025 but foresees U.S.-based jobs expanding after that along with the growth in OSW manufacturing and supply chains and the vessels needed to support installation activities.

The study breaks employment into five industry segments, including:

- Development, which could see average annual employment of 800 to 3,200 from 2024 to 2030 based on the 25%/100% domestic content scenarios. Job growth in this segment is expected to grow in parallel to increased use of domestic content. “The workforce need is likely closer to the upper limit because the United States has professionals and training programs to support a domestic workforce. Project development is underway, and many development jobs for initial offshore wind projects have been hired,” NREL said.

- Manufacturing and supply chain, which could support between 12,300 and 49,000 jobs, with the largest contribution coming from factory-level positions related to producing subcomponents, parts and materials for OSW installations. “The extent to which domestic jobs are realized depends on the building of U.S. manufacturing facilities and those facilities leveraging a U.S. supply chain to source subassemblies, parts and materials,” the report said.

- Ports and staging, which could account for 400 to 1,600 jobs a year, with the largest subset being terminal crews involved in stage components and load installation vessels. “Ports supporting offshore wind energy activities will support economic development in industrial waterfront communities by creating jobs,” NREL said.

- Maritime construction, with average annual employment levels estimated at between 500 and 2,100, although NREL notes that development of this domestic workforce is “highly uncertain” given the potential for different installation strategies and vessel availability. “Maritime construction workforce needs are estimated to develop slowly between 2022 and 2026, as we expect the initial offshore wind projects may use installation strategies

with foreign-flagged installation vessels with a larger international workforce. However, if Jones Act-compliant vessels are built to meet future development demand, we expect an increase in the domestic workforce need.” - Operations and maintenance, which could grow from 100 to 500 jobs in 2024 to 600 to 2,300 jobs in 2030. “O&M jobs will begin ramping up to support offshore wind energy plants in 2023-2024. O&M roles are needed throughout the wind plant’s life; therefore, workforce needs are cumulative, increasing based on the number, size and commissioning year of projects,” NREL said.

Good Timing

The NREL report also identifies the strategies needed to fill OSW-related jobs, including attracting and training skilled tradespeople; improving awareness of the roles required by the sector; clarifying and standardizing the credentials needed for those roles; helping workers from similar fields, such as offshore oil and gas, transfer into OSW jobs; focusing on developing a local workforce in communities affected by OSW development and prioritizing members of underserved populations; and increasing coordination across states and regions to develop workforce training and education programs.

The report also points to a need for coordination of installation activities across OSW projects to account for the variability in demand for certain types of workers along the timeline of an individual project’s development.

“The types, numbers and geographic locations of jobs vary during an offshore wind power plant’s life and, when considered across the pipeline of projects across the United States, can lead to large variability in workforce demand,” the study said. “Therefore, workers should be trained and hired strategically to alleviate potential peaks and troughs of workforce demand. For example, jobs related to installation activities are temporary, but a large deployment pipeline allows workers to move to other projects if those projects are properly timed.”