A study conducted for the California Public Utilities Commission finds that without mitigation, the distribution grids of the state’s three large investor-owned utilities will require up to $50 billion in upgrades by 2035, mainly to accommodate electric vehicle charging.

The Electrification Impacts Study, performed by energy analytics firm Kevala, was commissioned by CPUC as part of its High Distributed Energy Resources Grid Planning rulemaking, which is intended to prepare the state for large-scale transportation and building electrification.

California law requires that all new vehicles sold in-state be zero-emitting by 2035, and the state Air Resources Board is weighing a ban on sales of new natural gas-powered space and water heaters for residential and commercial use. (See Calif. Considers Zero-emission Appliance Rules.)

The study takes these high-electrification scenarios into account. Kevala and CPUC released the findings from its first part May 9 and plan to review the results in a public workshop May 17.

The findings provide preliminary estimates of the impact of widespread transportation electrification on the grids of Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E), Southern California Edison (SCE) and San Diego Gas & Electric (SDG&E) using a “highly granular load forecast” for more than 12 million homes.

“It is important to highlight that this Part 1 analysis was conducted under unmitigated planning scenarios, which assume only traditional utility distribution infrastructure investments,” the study says. The study also assumed that existing time-of-use rates and behind-the-meter solar tariffs would be in place throughout the study period.

“It did not consider alternatives or future potential mitigation strategies such as alternative time-variant rates or dynamic rates and flexible load management strategies,” the study says.

“Across these unmitigated load scenarios, Kevala estimates up to $50 billion in traditional electricity distribution grid infrastructure investments by 2035,” it says. “This estimate reflects distribution grid needs across the PG&E, SCE and SDG&E service territories under the policy assumptions used in this report.”

Two high transportation electrification scenarios would require the utilities to nearly double their current spending on feeder lines, transformer banks and substations, it says.

“Secondary transformer and service upgrades alone … [comprise] an estimated $15 billion of the $50 billion … and are currently not accounted for” in the investor-owned utilities’ annual assessments of grid needs, it says.

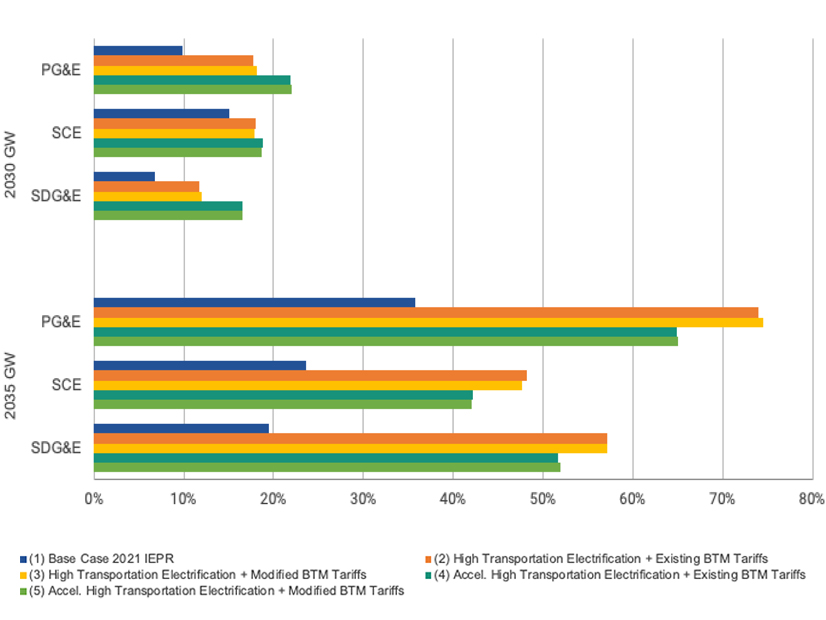

“PG&E’s distribution circuits are projected to reach capacity sooner than SCE and SDG&E,” it says. “SDG&E is expected to have the least number of feeders reaching full capacity by 2035, with 22% compared to SCE’s 36% and PG&E’s 48% of feeders.”

The study forecasts that peak load will increase on the utilities’ distribution systems an average of 56% from 2025 to 2035 under all high-electrification and base-case scenarios.

“This dramatic increase in peak load … is primarily due to transportation electrification impacts, with over 60% of this demand coming from light-duty vehicles,” it says. “The average percent change in peak load from 2025 to 2035 for the high transportation electrification scenarios is more dramatic for PG&E (69%), followed by SDG&E (53%) and SCE (44%).”

Among the study’s recommendations is that the utilities increase their distribution planning horizons to align with those of CAISO and the California Energy Commission, which stretch from 10 to 20 years. That would help them prepare more efficiently for a distribution grid that can incorporate DERs and manage load, it says.

“The substantial difference between the estimated capacity expansion costs, in the several tens of billions of dollars, in this study and the recent filings by the [utilities] suggest there is a disconnect between the data and the current planning process,” it says.

Another recommendation is for the utilities to better incorporate the state’s policy goals in their distribution planning.

A second part of the study will build on the first part’s findings, including by developing scenarios that reflect state policy goals, state agency targets and the Energy Commission’s demand forecast.