PORTLAND, Maine — In a cramped downtown rental office space, a group of volunteers, environmental advocates and a few paid organizers make small talk, strategize and practice talking to voters about one of the most consequential climate elections of 2023.

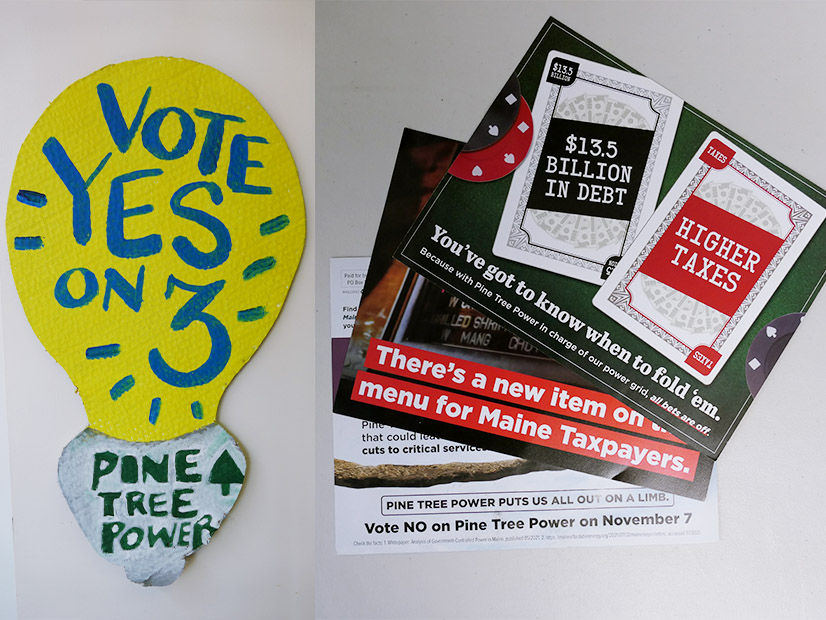

Hand-painted signs, made the night before, are hung up on the wall and occasionally fall to the floor, only to be hung right back up. There is too little seating to accommodate all of the volunteers cramming into the office, so half of the people stand through the hour of training.

The campaign, which goes by the name “Our Power,” is trying to rally Maine voters to support a ballot question that would initiate a state takeover of Maine’s two investor-owned electric utilities, creating in their place a publicly run utility called Pine Tree Power, governed by board members who would be elected by Maine voters.

The strategy of the Our Power campaign has consisted largely of trying to convince Mainers on the referendum one voter at a time, either by phone or old-fashioned door knocking.

Our Power is attempting to overcome a multimillion-dollar disadvantage; the parent companies of the two investor-owned utility companies subject to the takeover so far have committed about $27 million opposing the ballot measure, flooding Maine residents with a barrage of advertisements warning of the dangers of a public takeover.

In contrast, the Our Power ballot question committee has taken in about $800,000 in contributions and has about $50,000 in cash on hand according to its most recent disclosures.

For some proponents of the ballot measure, the main issues of the referendum are cost and reliability. Central Maine Power (CMP) and Versant, the two investor-owned utilities in Maine, were the lowest ranked eastern region utilities in customer satisfaction in 2022 according to J.D. Power. A 2021 report by the nonprofit Citizens Utility Board ranked Maine 42nd among all states and the District of Columbia on overall utility performance, with the state scoring particularly poorly on reliability.

But for another portion of the movement — including some of the major environmental groups that have endorsed the initiative — the climate implications of the ballot question are equally important, and some see the campaign as a potential blueprint for other regions to follow. Both proponents and opponents of the referendum largely agree the outcome of November’s vote could have major implications on the state’s ability to decarbonize rapidly.

“The climate fight is a class war, and the utilities are a perfect example of what that looks like,” said Candice Fortin, U.S. Campaigns Manager for 350.org, a climate organization that has endorsed the campaign. “A handful of people are making billions and billions of dollars and everyone else has to suffer. It’s not OK.”

On the other side, the utility-funded opposition campaigns also put a focus on climate impacts while making their case against the ballot measure.

“We don’t know the ways that Pine Tree Power will try to achieve our renewable energy goals, and it’s a massive risk that shows that there’s a significant potential that Maine would be taken off from the great progress that we’ve made,” said BJ McCollister, president of the Resurgam Group, a public affairs firm hired by Maine Energy Progress, a ballot question committee funded by Versant Power’s parent company ENMAX.

Dueling Climate Claims

Both Maine Energy Progress and Maine Affordable Energy — the latter of which is backed by more than $18 million from CMP’s parent company Avangrid — have run ads arguing the switch to a utility could inhibit clean energy.

“Big oil and gas companies spend millions influencing politics,” reads a Facebook ad by Maine Energy Progress. “Putting politicians in charge of our electric grid would put Maine’s progress on clean energy at risk.”

A range of climate-focused nonprofits have endorsed the public takeover, including the Sierra Club, Environment Maine, Maine Youth for Climate Justice, Maine Climate Action Now and several local Sunrise Movement hubs.

Meanwhile, McCollister and Versant have argued the absences from this list of supporters are just as important. While no major climate organizations have announced their opposition to the measure, groups including Maine Conservation Voters and the Natural Resources Council of Maine have remained neutral.

“Utility leadership absolutely matters when it comes to climate action and environmental impacts,” said Kathleen Meil, senior director of policy and partnerships at Maine Conservation Voters, which underwent a lengthy process around its stance on the referendum, ultimately deciding on a position of neutrality. “What wasn’t clear was whether utility ownership structure is the critical factor.”

However, Meil emphasized that Maine Conservation Voters’ position is neither an endorsement of the status quo nor a vote of confidence in the state’s utilities.

“When Paul LePage was governor, he was a climate denier, and he was strongly opposed to climate action, clean energy progress, and really thwarted the best efforts of the climate action and clean energy movements,” Meil said. “During that era, he had the support and the partnership of the utilities in thwarting that clean energy progress.”

Following LePage’s election, along with Republicans taking control of the Legislature in 2010, the state worked to roll back programs around solar rebates and net metering. During the Republican governor’s tenure, CMP lobbied against a bill to save the state’s net metering program, which LePage ultimately vetoed. Soon after the veto, a firm employed by CMP to lobby against the bill announced the hiring of LePage’s daughter.

Seth Berry, former Democratic majority leader of the Maine House of Representatives and three-term House chair of the Joint Standing Committee on Energy, Utilities and Technology, said that even prior to the LePage era, the investor-owned utility companies were “deeply opposed” to policy promoting distributed energy and energy efficiency at the state level.

“We were stymied at every turn not by the large fossil fuel lobby… but by the electricity delivery utilities,” Berry said. “I was just shocked and horrified, like how could we let this happen? How could the system evolve to be so incredibly dysfunctional?”

In 2021, Berry was the lead House sponsor of L.D. 1708, a bill that would have directed the public takeover of CMP and Versant, subject to the approval of Maine voters.

Although the bill passed through the Maine House and Senate with bipartisan support, it ultimately was vetoed by Democratic Gov. Janet Mills. While Mills called the performance of Maine’s investor-owned utilities “abysmal” and did not rule out her support for a public takeover in the future, she called the bill “a patchwork of political promises,” and expressed concern that a lengthy takeover process would delay necessary climate investments in the grid.

Mills has yet to take a public stance on the current ballot referendum facing voters.

Representatives for Avangrid and Versant said the companies support Maine’s transition to clean energy, and do not oppose climate policy generally in the state.

“As a company, CMP strongly supports Maine’s clean energy transition and Maine’s climate action goals,” said Jonathan Breed of Avangrid. “To meet this end, we look to seek a fair and balanced compromise on policies that continue to build on the environmental progress already made while not overburdening our customers.”

The utilities and their respective ballot question committees argue that establishing an elected board to run Pine Tree Power would increase the impact of corporate influence on utility policy.

“The question here is: do you want energy companies to be influencing policy — electric policy, utility policy and environmental policy? If the answer is no, then you probably don’t want this Pine Tree Power referendum to pass,” said Willy Ritch of Maine Affordable Energy. “If, for example, a bunch of oil and gas and fossil fuel interests successfully financed the campaigns of all the people that ran for that board, then maybe those people would not be as interested and willing to make the investments necessary to hook up more renewables.”

Although Avangrid has made significant investments in renewable power along the East Coast, the company also owns a considerable amount of natural gas infrastructure, including gas utilities in Maine, Connecticut, Massachusetts and New York. ENMAX owns a gas distribution network in Alberta, as well as more than 1,000 MW of gas generation.

“CMP and Versant are literally owned by multinational corporations that have their hands all in the oil and gas industry,” said Lucy Hochschartner, deputy campaign manager for Our Power. “They’re only controlled by executives who are accountable to no voters.”

Interconnection Woes

Another point of contention on the climate impacts of the referendum is whether a non-profit utility company would be able to significantly improve on the interconnection processes of the investor-owned utilities, which have come under fire from distributed energy developers in the state.

“CMP and Versant are doing an abysmal job interconnecting clean energy, so much so that the Legislature had to set up additional metrics and fines related to interconnections and require the utilities to do grid planning,” said state Sen. Nicole Grohoski, a member of the Energy, Utilities and Technology committee.

“I get regular complaints from residential rooftop solar customers who have been told by Versant that transformer upgrades needed for interconnection will take two years,” Grohoski added. “Mysteriously, when I point my constituents to the PUC’s dispute resolution process, Versant installs the equipment they need in two months.”

In early 2021, the Maine Public Utility Commission (PUC) opened a docket (2021-00035) looking at the interconnection practices of CMP following a request for an investigation by the Coalition for Community Solar Access and the Maine Renewable Energy Association.

The renewable energy groups allege that several of their members had received significant unanticipated notices of interconnection cost increases.

“These notices were provided to a number of Interconnecting Customers following the completion of the projects’ Impact Study, and immediately prior to execution of the Interconnection Agreement (IA) by CMP,” the renewable energy groups wrote in their request to the PUC. “It is highly unacceptable and unprecedented for a utility to identify entirely new interconnection scope items after the fact and to require a developer to pay for additional costs not contemplated in the System Impact Study.”

In March of 2022, the PUC accepted an agreement between CMP and the clean energy groups which included several provisions including the requirement that CMP must spend $700,000 to boost their interconnection processes. Following the agreement, the clean energy groups argued CMP failed to fulfill the requirements of the agreement, and the docket remains ongoing.

Judy Long of Versant Power defended the company’s record on interconnection to NetZero Insider, saying that while staffing difficulties and growing interest in clean energy subsidies have led to lengthy connection queues, the company is committed to reducing the amount of time it takes to connect projects to the grid.

“We’ve got the largest team in our company working on distributed generation, and we’re trying to work with developers to find ways so we can accommodate them,” Long said.

Breed said the contention CMP has delayed the interconnection of renewables demonstrates a “lack of understanding of the solar interconnection process in Maine given that interconnection cost responsibilities and timelines are governed by Maine PUC rules, not CMP or any other utility.”

“As a regulated utility company, the Maine PUC says it is our role in the interconnection process to systematically understand how new generation assets will affect the distribution of electricity to our customers, and to ensure power delivery remains safe and reliable,” Breed added. “We do not benefit or lose financially.”

A Blueprint for Future Campaigns

While only a handful of large national climate and environmental groups have taken a stance on the referendum, those that have endorsed the campaign see potential for expanding the public power movement well past Maine’s borders.

Proponents of the takeover point to the fact that the earliest communities to reach 100% clean energy in the U.S. are disproportionately served by municipal or co-op utilities, including Aspen, Colo.; Georgetown, Texas; Greensburg, Kan.; Kodiak, Alaska; Rock Port, Mo. and Burlington, Vt.

In his endorsement of the campaign, Bill McKibben, a high-profile climate author and one of the founders of 350.org, emphasized the nationwide potential of the movement.

“Maine’s proposal for a consumer-owned utility offers a model for transforming a nation and a world seeking solutions to the crisis of our era,” McKibben said.

In the Sierra Club’s endorsement, the nonprofit called the potential move to a publicly owned utility a “nation-leading step to protect consumers and the planet.”

Hochschartner stressed that the Our Power campaign remains focused on the specific issues facing Maine, but said the structural issues related to investor-owned utilities exist throughout the country.

“The model right now with investor-owned utilities is so fundamentally broken,” Hochschartner said. “This is really something that has the opportunity to be transformative nationwide.”