The building sector has the potential to move from being a massive emissions source to a carbon sink, a new report said.

The building construction sector has the potential to move from being a massive emissions source to a carbon sink, a new report said.

Driving Action on Embodied Carbon in Buildings, jointly released by RMI and the U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC), looks at challenges in reducing embodied carbon emissions in the building construction sector and the potential for reducing and even negating those emissions.

“In our lifetimes, we could see buildings move from being leading drivers of climate change to safely and durably storing gigatons of atmospheric carbon,” the report said. “There is a long way to go to achieve such an ambitious goal, but it is not as far-fetched as it may seem. Buildings currently account for nearly 50% of global material flows. Only a small percentage of that material would need to store carbon to become a leading climate drawdown solution.”

When looking at greenhouse gas emissions reduction, the focus is often on energy consumed by buildings’ operations and how it can be cut through energy efficiency. The International Energy Agency says operating buildings and the appliances and equipment in them accounts for more than one-third of global energy use and emissions, but that figure doesn’t account for the buildings themselves.

The carbon embodied in the buildings includes the carbon emissions from the energy used in extracting, processing and transporting materials, equipment and fixtures, and constructing buildings, as well as managing the waste at the end of the building’s life. The World Green Building Council estimates buildings’ material and construction accounts for 11% of global energy-related carbon emissions. And it is why everyone in the green building industry winces when another video of imploding, never-occupied high rises in China makes the rounds on social media.

“Given the scale of the sector’s climate impact, it is imperative that owners, designers, builders, manufacturers and policymakers lead the market by prioritizing this issue,” the report said.

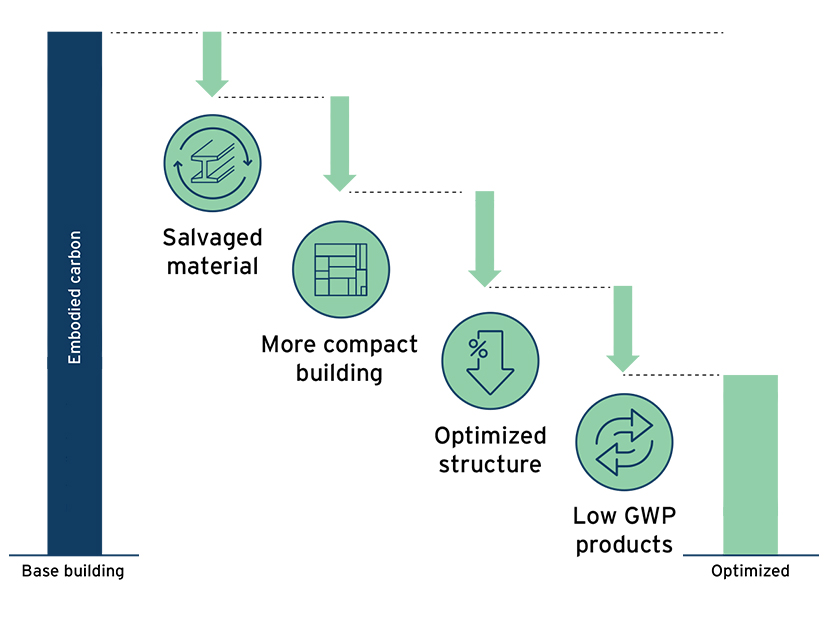

There are already cost-effective ways to reduce buildings’ embodied carbon. The report quoted an RMI study that showed it is possible to reduce the upfront carbon footprint of common building types between 19 and 46% with little to no added expense by making more informed materials choices.

Across all building materials, there are critical data gaps when it comes to measuring the lifecycle emissions of materials. “Currently, the most accurate data points exist for cradle-to-gate emissions in key building material categories including concrete, masonry, steel, aluminum, gypsum board, insulation, cladding, flooring, ceiling tiles and paint,” the report said. Emissions after “the gate” — transportation from the factory to the building site and construction itself — are less well understood.

Data gaps, however, are not a reason to delay action, the report said. “We know enough today to make meaningful decisions that reduce building embodied carbon emissions and should not let data gaps stop rapid uptake of low-embodied-carbon strategies in rating systems, policies and codes.”

Tackling The Big Three: Concrete, Steel And … Wood?

The potential to cut the embodied carbon of buildings in the future looks even better as innovations in the production of key building materials, especially energy-intensive concrete and steel, drive down their embodied energy. “Transition away from fossil fuel production of concrete and steel combined with the rapid decarbonization of the grid portends a future where the embodied carbon of these materials can approach zero emissions,” the report said.

Wood too has the potential to be improved, and it may not be as green as it may sound. “Wood used in building products has the potential to be a renewable and perhaps carbon-storing material that can help drive down embodied carbon emissions when efficiently substituted for high-impact materials. However, there are aspects of wood sourcing — such as forestry practices with poor climate outcomes, wider land-use impacts and energy-intensive product manufacturing — that can lead wood to have high emission and ecological impacts.”

Updates Can Double Embodied Energy

The embodied carbon from retrofits and renovations over the lifetime of a building may equal or exceed that of the initial construction, the report said, and is “poorly understood but could be a major driver of emissions if left unaddressed.” Avoiding, delaying or limiting the scope of updates, disassembling instead of demolishing and increasing materials recycling can all lower the impact of renovations.

Renovations, though, offer potential for carbon drawdown. “Interior finishes represent some of the best opportunities to incorporate carbon-storing, rapidly renewable, bio-based materials that are not subject to exterior weathering,” such as bamboo flooring and cellulose acoustic panels, the report said.