CAISO stakeholders and staff could soon be weighing two options for enabling the EDAM to track GHGs in a way that accommodates the patchwork of different carbon reduction programs across Western states.

CAISO stakeholders and staff soon could be weighing two options for how the Extended Day-Ahead Market (EDAM) would track and account for greenhouse gases in a way that accommodates the patchwork of different carbon pricing programs across Western states.

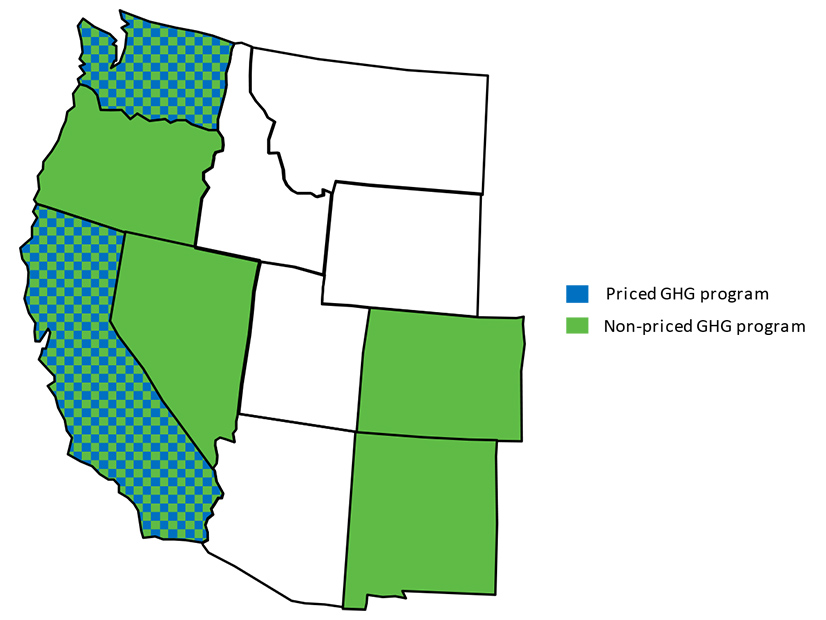

Speaking at a March 14 meeting of the ISO’s Greenhouse Gas Coordination Working Group, Doug Howe, GHG policy consultant with the Western Climate Action MOU Group, delved into how the different carbon reduction programs among Western states complicate accounting for GHGs in EDAM. Some states — such as California and Washington — price emissions through cap-and-trade systems while many others seek to limit with “non-priced” GHG programs such as targets for declining emissions for utilities.

“For a standalone utility not in a day-ahead market, compliance would be a relatively straightforward procurement issue,” said Howe, a former member of the Western Energy Imbalance Market’s Governing Body. “In a day-ahead market, compliance would certainly still require the utility to procure the needed resources, but the added complexity is that of imports and exports through the market — specifically, how to account for imports and exports to report on compliance.

“At a minimum, a thorough tracking and accounting system would be required that provides emissions attribution to all market transfers to avoid over- or undercounting.”

In contrast to priced programs that place responsibility for compliance on the emitting resource, non-priced programs regulate the load-serving entity and require compliance across a longer time frame, often a year or more. When referring to non-priced programs, Howe excluded renewable portfolio standard programs, which exist in some form in every state in the Western Interconnection except for Wyoming and Idaho.

Non-priced Challenges

The variety of GHG programs across the Western Interconnection means some states will require utilities to make aggressive emissions reductions as early as 2030 while others face no obligation to reduce.

One of the main components needed to ensure GHG compliance within EDAM is “control” — or the ability of a market participant subject to a GHG program to have a say in what is imported into and exported out of its area, Howe said. That goes for utilities subject to non-priced programs as well as those operating underpriced programs.

The variations in average emissions rates among Western states presents a key challenge for designing GHG market mechanisms that satisfy the needs of states with non-priced programs, Howe explained. While the relatively low emissions rates in the Pacific Northwest could help utilities there become compliant with their non-priced GHG mandates, the higher rates in Rocky Mountain and Desert Southwest regions indicate utilities in those regions might struggle to comply with 2030 mandates.

Pointing to patterns already seen in CAISO’s Western Energy Imbalance Market (WEIM), Howe said he expects “GHG competition will emerge” in EDAM, with the priced programs in California and Washington drawing in the lowest-emission resources first.

“This means higher-emitting resources will comprise the bulk of market imports and exports between utilities subject to non-priced GHG programs,” he said.

“Given how we see the landscape emerging, we took on the exercise of thinking through other options that might allow the utility to garner economic benefits of being in the market without having to self-schedule significant parts of its portfolio, but at the same time have some control of the carbon content of its market imports and exports to ensure compliance,” Howe said.

Howe presented two mechanisms to address the problem: the emissions constraint method and an import constraint method.

In the emissions constraint method, a non-priced GHG zone establishes a maximum emissions rate for the dispatch interval and the market optimization chooses which resources’ energy and emissions will be attributed to priced zones.

“It’s important for me to say that this method does not attribute only resources that can meet the specific emission rate. Rather, it selects resources that, as a pool of resources, can meet the maximum emission rate and energy requirements of the non-priced GHG zone,” Howe said. “A higher-emitting resource could be dispatched, be assigned to the non-priced GHG zone and be offset by a lower-emitting resource.”

A non-priced GHG zone would operate under a must-offer obligation, meaning it’s obligated to offer a portfolio of generation that meets its load and the maximum emission rate set for the interval. Whenever the emission constraint is enabled, the must-offer obligation must be met.

This method produces both an energy marginal cost and a GHG marginal cost, with resources attributed to the non-priced zone would be receiving payment from load for both costs, raising what Howe identified as a central policy question: whether the GHG marginal cost should be paid to generators.

To address that question, Howe presented the second mechanism: the import constraint method.

“Are there some ways that we can maybe avoid that kind of GHG marginal cost policy question of, ‘Should it be paid or should it not be paid?’ Because it’s a very thorny question,” he said.

The import constraint method has many similarities to the other method, including allowing the utility to specify the maximum emissions target with a must-offer obligation and not requiring the constraint in every interval. The difference, though, is that external resources would not be attributed to non-priced GHG zones, which “effectively moots” the question of whether attribution should be voluntary. Instead, emissions attributed to non-priced zones would be computed as emissions from internal generation and market imports, minus emissions from exports.

“In this case, the optimization will choose the internal generation and the amount imported and exported to minimize the total system costs while still meeting the maximum emission rate,” Howe said. “But to do this, we have to establish an imported emissions rate and an exported emissions rate, very much like the residual emissions rate” the Western Power Trading Forum (WPTF) discussed in another presentation.

Residual Emissions Rate

“We really believe that we should have a long-term goal of developing a better tracking and accounting system for the market to accurately account for energy and to accurately account for emissions,” Clare Breidenich, assistant executive director at WPTF, said in presenting another approach for GHG accounting.

Central to Breidenich’s proposal was use of residual market supply — energy not committed to market participants or attributed to GHG regulation areas. It determines the residual emission rate, a dispatch-weighted average emission rate of the market supply.

If the market can ensure that entities are able to claim and procure their own resources to meet load, Breidenich said, then what is left is a relatively small increment of energy, which is the residual market supply.

“If we can do a better job accounting for that increment of energy, as well as do a better job of accounting for the emission rate of that increment, it’s not clear to us that there really is a need for a dispatch mechanism,” Breidenich said.

Power producers first need to agree on a set of accounting rules and an emission rate that determines what is in the residual supply, then determine how to match resource claims to dispatched energy and associated emissions and place them into entity accounts for correct attribution. Lastly, a reporting and publication system would be needed for producers and regulators.

Under this framework, leftover energy in the market would go into the residual supply, and the emissions rate would be the average of the residual mix.

The benefit of this approach, Breidenich said, is that it ensures all entities subject to GHG regulations can account for energy and emissions without imposing requirements or costs on LSEs and energy users in non-GHG areas.

Regardless, she said, CAISO staff and stakeholders need to have a unifying assumption for how to treat attribution of energy and emissions throughout the states.

“I appreciate the point about ensuring that we’re able to capture the generation associated with those non-price-based states that don’t have a clean energy policy in place,” said Anja Gilbert, lead policy developer at CAISO. “This is a recommendation put forth, but the states are going to have to opine in terms of, does this meet their requirements? And so, I’m really seeing this as [a situation in which] there could be multiple approaches just based on what different states choose to adopt.”

But Mary Wiencke, executive director of Public Generating Pool, questioned whether the accounting framework could be applied consistently across states.

“Within this framework, there may be areas of users’ choice that we can identify and then work within that framework with states to work toward consistency,” Wiencke said. “I also think there may be areas that just can’t be reconciled between different state policies.”

Despite unresolved questions, stakeholders concluded on a positive note.

“I know there’s a lot here, and this does imply a lot of work … but now is the time to start getting the accounting system right,” Breidenich said.

“I think it’s a step beyond a lot of what we’ve been thinking about in terms of leveraging averages and data to really support some of the transfer attribution that we see through the market,” said Pamela Sporborg, director of transmission and market services at Portland General Electric. “I actually have hope for maybe the first time ever.”