Performance-based regulation is a way to align utility incentives with the interests of customers and society, according to a new RMI report.

Performance-based regulation is a way to align utility incentives with the interests of customers and society, according to a new RMI report that seeks to get more states to adopt the practice over traditional cost-of-service regulation.

Traditional regulation has strong financial incentives for utilities to spend more money than needed on infrastructure, leading to affordability concerns as the industry invests to transition to a modern, cleaner grid, said the report, titled “How to Restructure Utility Incentives: The Four Pillars of Comprehensive Performance-Based Regulation.”

“There’s a number of reasons the traditional model just isn’t really well aligned with the challenges today,” report co-author Kaja Rebane, an RMI senior associate, said in an interview. “Affordability is a very big one of those. Right now, we are facing the need to invest a lot of money in the grid [to] modernize it, to deploy new technologies and to just build more capacity to supply clean power to customers.”

Traditional regulation pays utilities for what they build, while performance-based regulation (PBR) focuses on what they achieve, she added. Utilities will consider a number of factors when they make investments, but regulations guaranteeing them a return on capital are a major influence.

“That’s not … well-aligned with what the challenge is today,” Rebane said. “We do need more capital spending that is important, but we need it to be cost-efficient in order to achieve what we want to achieve in an affordable manner.”

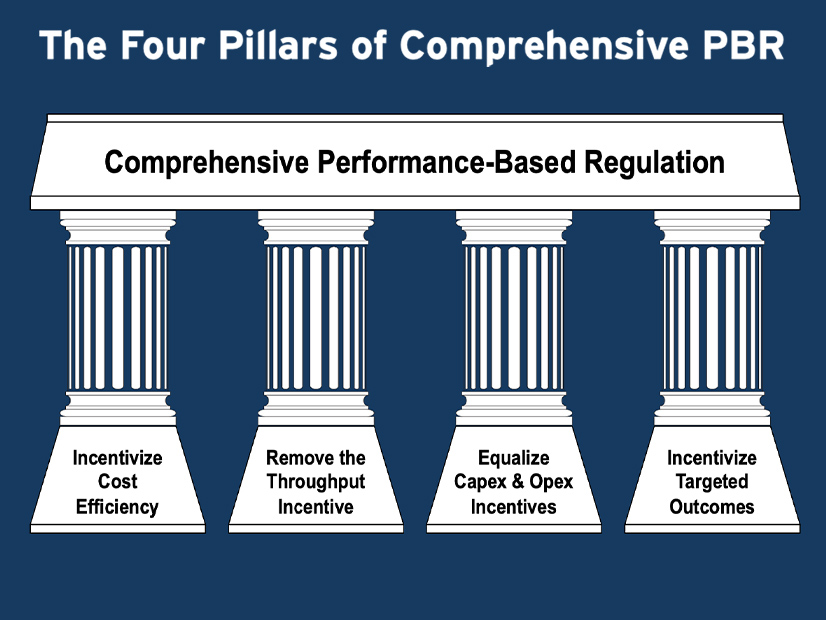

Getting the right regulatory incentives sounds easier than it is because a full suite of performance-based regulations requires multiple changes to the cost-of-service model. The report said regulators can do “incremental PBR” and adopt some specific tools onto traditional regulation, or “comprehensive PBR,” adopting the full suite of reforms to get utilities focused on outcomes in ways cost-of-service regulation cannot.

The report lays out four pillars of performance-based regulation: incentivize cost efficiency, remove the throughput incentive, equalize capital and operational spending incentives, and incentivize targeted outcomes.

Cost efficiency can be supported by an array of changes, such as multiyear rate plans, shared savings mechanisms, fuel-cost sharing mechanisms and metrics focused on spending trends.

Revenue decoupling is the main way to remove the throughput incentive, while equalizing returns for capital and operational returns is self-explanatory. Incentivizing targeted outcomes can be accomplished through metrics, scorecards and performance incentive mechanisms (PIMs).

“Although PBR can be powerful, it is not a silver bullet for every regulatory problem,” the report said. “Even a well-designed comprehensive PBR framework will achieve the best results when it is part of a larger basket of synergistic reforms, such as widening opportunities for stakeholder input, adopting innovation policies, updating planning and procurement processes, and expanding regulatory commission authority and responsibilities.”

PBR in Hawaii

The report highlights Hawaii as a jurisdiction that has adopted comprehensive PBR across the four pillars.

“We highlighted Hawaii, in part, because it really has adopted a framework we would consider comprehensive, meaning that all four pillars that we discussed in the report are supported,” Rebane said. “There’s also been a number of forward-looking reforms in Hawaii that are worth highlighting.”

Hawaii has a five-year multiyear rate plan (MRP) with returns pegged to third-party indexes instead of utility forecasts, she added.

To mitigate excessive earnings or losses, the five-year rate plan comes with an earnings-sharing mechanism with a wide symmetrical deadband to ensure cost efficiency, the report said.

“Because of the deadband, which is centered around an allowed ROE of 9.5%, the MRP’s full cost-containment incentive is preserved (i.e., Hawaiian Electric keeps all additional earnings and bears all deficits) when the realized ROE falls between 6.5 and 12.5%,” the report said. “Outside of the deadband, sharing ramps up in a tiered fashion.”

A shared savings mechanism encourages cost efficiency for operational costs not covered by the annual revenue adjustment in the rate plan, which covers fuel for generators, purchased energy and capacity costs, new projects not funded with the rate plan, and other items. A fuel-cost sharing mechanism trues up just 98% of the difference between expected and actual costs — subject to a $2.5 million annual cap, which gives Hawaiian Electric the incentive to operate its generation more efficiently.

Hawaii regulators have also adopted metrics and scorecards that provide visibility into the utility’s cost trends, which include rate base per customer, operations and maintenance cost per customer, and annual revenue growth.

The term performance-based regulation has been around a while, and RMI hopes its report will help regulators better understand what it means and how it can improve outcomes in their jurisdictions, Rebane said.

“We’re trying to give regulators the tools they need to really reform incentives in their jurisdictions to achieve their policy goals,” Rebane said. “We also, of course, in the report provide kind of a relatively basic overview of a number of the key PBR tools that can support each pillar and so, hopefully, that will provide something of a go-to reference for regulators who are interested in these things.”