WASHINGTON — If SouthWestern Power Group had known how difficult and expensive its SunZia transmission project would be, the company probably wouldn’t have pursued it, General Manager David Getts said.

Getts has been working for 16 years on SunZia, a project to deliver wind power from sparsely populated New Mexico into Arizona for consumption there and in California. It’s taken so long that the company is now on its fourth law firm — and fourth presidential administration, dating back to that of George W. Bush. The Phoenix-based company has spent $200 million to date, thanks to backing from parent MMR Group, a large, privately held electrical contractor based in Baton Rouge, La.

Getts recounted his SunZia experience at the Energy Bar Association annual meeting last week, a cautionary tale with implications for the nation’s climate policy.

“It’s an incredible amount of money for a private company. Putting that much money at risk in one project is kind of crazy. I thank my chairman and his faith and support and my team over 16 years. But that’s not repeatable. Very few companies in the U.S. will ever do that again. I can tell you my company won’t.”

Conception

SouthWestern began discussing the idea of a transmission project with regional utilities and renewable developers in 2006.

“We knew that New Mexico had great wind energy. And New Mexico [population 2.1 million] has very few people,” meaning the power would need to be exported, Getts recalled.

David Getts, SouthWestern Power Group | © RTO Insider LLC

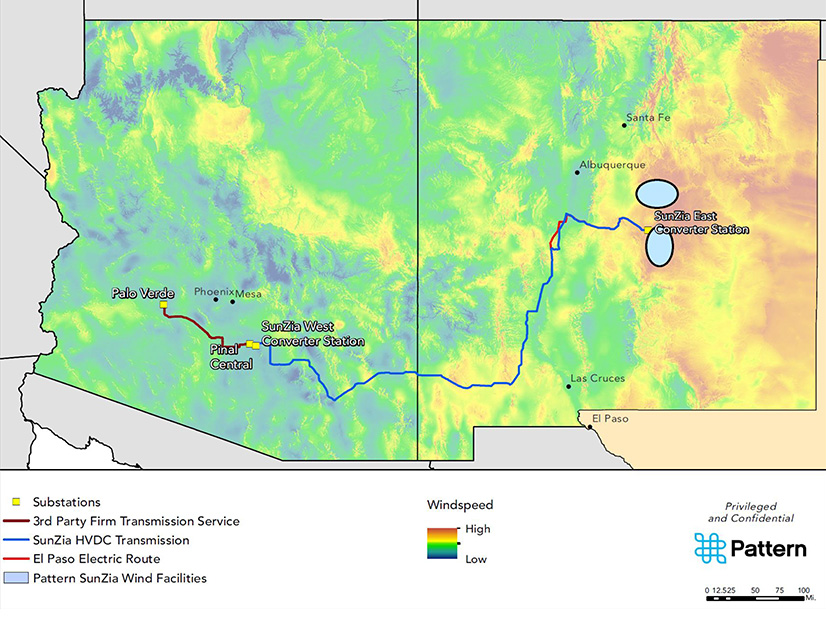

David Getts, SouthWestern Power Group | © RTO Insider LLCThe developers decided the project would run from near Corona in central New Mexico, where there is more than 4,500 MW of wind energy capacity. Two 500-kV lines would run 550 miles southwest to the existing Pinal Central substation in Pinal County, Ariz.

“It’s a really good place to get from there to the Palo Verde hub. That’s really important in the West; not only is it a liquid market, but it’s a gateway to California electrically,” Getts explained. “The California ISO can take delivery of electrical energy that’s delivered to Palo Verde, and there’s an awful lot of generation interconnected there.”

In 2011, FERC approved a request to commit half of the project’s capacity to anchor tenants. In 2016, SouthWestern selected a tenant through a solicitation: Western Spirit Wind Farm, a group of wind energy projects totaling 3,000 MW being developed by Pattern Energy.

“There’s hardly any available transmission capacity in the West. So the wind depends on the line, [and] the line depends on the wind,” Getts said. “That meant from the very early days, we knew that we would have to find someone to work with us. And in fact, the projects will be financed as a unit, because of what we call in financing circles project-on-project risk. That’s a real issue for any independent project.”

Siting

Having decided on its partner, the developers needed to site the line. “That’s a little more than just drawing lines on the map,” he said. “Siting is key because that will define your permitting destinies. Permitting is something that, you know, has really takes the lion’s share of time.”

Getts said even electric utilities with eminent domain rights work hard not to use them.

“The difference is, if you have them [and] everybody knows it, you’re in a much better position. Because if you don’t have it, or if what you have is arguable or questionable … then you’re at the mercy of your private landowners. We’ve experienced that. And the only solution is you pull out your checkbook, and you just pay.”

Southwestern and Pattern worked with the New Mexico Renewable Energy Transmission Authority, which was created to facilitate the development of transmission projects and has eminent domain rights that potentially could help transmission developers. “Our state permit, in theory, conveys the powers of eminent domain,” Getts said. “However, there’s a big question mark if it’s enforceable. And it has to do with the fact that we may or may not be a public service corporation.”

SouthWestern had to negotiate access with federal, state and private landowners. “We were able to try and address local concerns and issues because we could reroute. And we’ve done that a lot, particularly to get around private landowner concerns.”

NEPA

It took eight years to win approval from the Bureau of Land Management for a 400-foot-wide right of way over 183 miles of federal land. To get through its National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) review the first time took seven years. Getts expects it will take another three years to win NEPA approval for its revised plan, which realigns about 100 miles of the route to add roadways, avoid conflicts with the White Sands Missile Range and add a DC-to-AC converter.

The developers avoided tribal lands. “And that’s difficult in the West because there are a lot of tribal reservations,” Getts said. “As a private sector developer — where it was 100% of my company’s private capital we were putting at risk — we felt it was to our advantage to try and not put our transmission line through reservations. Not saying it can’t be done; just add another maybe 10 years to your time.”

The developers now have all the right of way for line 1, which will be HVDC, with a capacity of 3 GW. They plan to build that before moving to the second line, which would be AC with a capacity of 1.5 GW. “We aren’t going to be able to get the second line done if we don’t get the first line into construction,” Getts said.

Construction of the transmission and the wind farms is expected to begin next year and take up to three years, meaning it all could be in operation by the end of 2025 — or 20 years from the beginning of development to commercial service. Of the project’s early utility investors, only Salt River Project remains, with SouthWestern having bought out the interests of Tri- State Generation and Transmission Association and Tucson Electric Power.

“Obviously, that’s not a very good model for building all of the bulk power system [capacity] that we need to … achieve the [decarbonization] policy goals,” Getts said.

“When we started doing this, there were 40 or 50 independent projects. Today, there’s maybe three that are viable. I think SunZia will get built. Not that it’s a unicorn, but it’s not probably easily repeatable.”

Getts said he had no answers for improving the process. “NEPA does work. It just takes ages,” he said. “I’m not sure there’s a lot the federal government can do to make it better.”

FERC Backstop Authority

He said the backstop siting authority given to FERC in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act — which allows the commission to override state vetoes of transmission in areas designated by the Department of Energy as National Interest Electric Transmission Corridors — is no solution either.

“In my opinion, that’s never going to happen,” he said.

Kellie Donnelly, executive vice president and general counsel for government affairs and communications firm Lot Sixteen, also was skeptical that FERC will use the new authority.

Donnelly spoke along with Getts and Avi Zevin, the Department of Energy’s deputy general counsel for energy policy during the meeting’s Kevin J. McIntyre General Session, in a discussion moderated by Vinson & Elkins partner John Decker. (See related stories, DOE Seeks Input on Tx Loan, ‘Anchor Tenant’ Programs and Response to Russian Invasion Undermining Budget Reconciliation Effort, Former Murkowski Aide Says.)

“It is a potential tool, and it could be used for something like offshore wind,” said Donnelly, who served as general counsel to the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee under Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska).

“But I think FERC would prefer to have a more collaborative process with the states,” she added, citing the Joint Federal-State Task Force on Electric Transmission created by FERC Chairman Richard Glick. (See Task Force Seeks ‘Right Balance’ in Spreading Tx Upgrade Costs.)