Electricity cooperatives, independent power producers and biogas generators have asked IESO to reconsider key components of its proposed Local Generation Program.

Electricity cooperatives, independent power producers and biogas generators have asked IESO to reconsider key components of its proposed Local Generation Program, calling for longer contract terms and special consideration for some generation types.

Twenty-two organizations weighed in with written comments last month on the LGP, which is intended to retain local generation resources whose existing contracts are nearing expiration and provide additional capacity to meet rising demand.

IESO has contracts with about 2,500 facilities with installed capacities between 100 kW and 10 MW. Over the next decade, about 1,600 of the contracts — representing 2,000 of the total 3,300 MW of capacity — will expire. IESO forecasts Ontario’s electricity demand will increase by 75% by 2050 as a result of electrification and industrial and data center growth.

The grid operator says smaller, distribution-connected generation can be built more quickly than large-scale projects and help meet local demand, freeing up transmission capacity.

Generation sources of 100 kW to 10 MW would be eligible to participate in either the re-contracting stream, with proposed five-year contracts, or the new build program, for which IESO is proposing 20-year contracts.

Jonathan Scratch, IESO senior manager of market and system adequacy, said during a webinar in April that the grid operator hopes to sign new contracts with “the lowest-cost 80%” of facilities with target quantities reflecting provincial, local and regional energy needs. “[To be determined] on whether there would be price caps,” he said.

In selecting new projects, the grid operator said it also may weigh policy considerations such as economic participation in the project by an indigenous community and municipal and local distribution company support.

Contract Term

IESO proposed that generators be eligible to seek new contracts if their existing contracts are expiring within five years, making facilities with contracts expiring before 2031 eligible to bid during the 2026 application period.

It proposed five-year terms on renewed contracts, identical to its medium-term procurement program, which it runs every two to three years, as needed.

That is too short for some.

“Where a facility is being recontracted without any refurbishments, upgrades or expansions, the five-year term length proposed is sufficient,” wrote Community Energy Co-operatives Canada (CECC). “However, where any refurbishments, upgrades or expansions are undertaken, the term length of five years will not be sufficient to recoup those costs.”

The Canadian Biogas Association said the recontracting term should be 15 to 20 years to provide sufficient certainty to invest in maintenance and secure feedstock agreements.

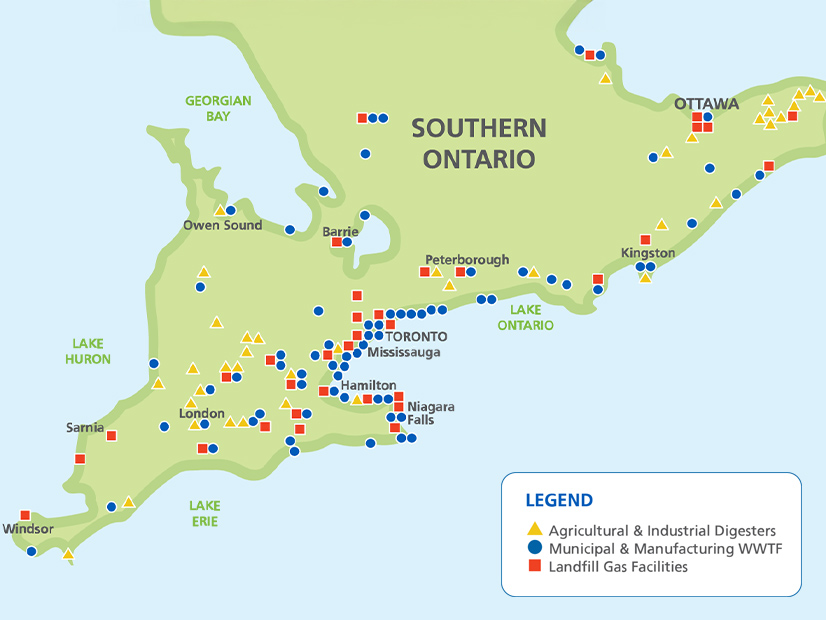

Twenty of Ontario’s 56 biogas facilities between 100 kW and 10 MW, totaling 79 MW, are seeking new contracts as soon as 2030. Most facilities are 250 kW to 1 MW, according to the group.

“A short-term contract, paired with frequent participating in competitive procurements, creates too much pricing and uncertainty risk for biogas developers,” it said. “Our industry and facility owners (many of whom are small-scale local farmers) will require a longer contract to ensure greater price stability and certainty for a longer term.

“For many facilities, the expiration of current contracts coincides with the end of their engines’ useful life. As a result, significant capital investments in upgrades or replacements may be required,” it added. “If the program does not provide sufficient value, permanent shutdowns may become necessary for some operators.”

The association also said smaller facilities will be at a competitive disadvantage versus larger projects using different technologies that can offer lower prices.

Independent power producer Capstone Infrastructure also called for lengthier contracts. It suggested suppliers be granted the flexibility to select a preferred contract length — with up to 30 years for new builds — which it said would produce lower-cost bids through better financing terms. “We are seeing other regions offer longer-term contracts, and this would align with where the industry is heading,” it said.

Standard Offer vs. Competitive Bidding

Power cooperatives and clean energy advocates also called for the use of standard offer contracts rather than competitive bidding.

The Ontario Clean Air Alliance said it favors competitive bidding for large generation projects. “But … IESO’s proposed LGP competitive bidding process for small power projects does not make sense, since it will impose onerous costs on participants and create unnecessary uncertainty as to whether their projects will be funded,” it said. “Instead of discouraging participation by creating needless red tape, the IESO should establish a fair market value standard offer price(s) for small-scale generation projects. All projects that are willing to accept the fair market value standard offer price(s) should be awarded contracts.”

IESO officials said they attempted to make the application less onerous for cooperatives.

“It sounds simple,” IESO’s Scratch said of the standard offer alternative. “It’s inherently not simple to make an assessment of what the right price is. … So, cognizant of that, we’ve set this up as simplified application process and … the dollar-per-megawatt-hour rate.”

Technology Agnostic

IESO’s proposal that new build procurements be technology agnostic drew mixed reaction, winning support from the Ontario Waterpower Association, which represents the hydropower industry, but opposition from the Canadian Biogas Association.

The biogas group said IESO should conduct technology-specific procurements to acknowledge “the unique operational characteristics, value propositions and cost structures associated with different generation technologies.”

“Biogas projects, in particular, provide distinct and system-critical benefits that are often undervalued in competitive procurement processes when assessed alongside technologies with inherently different generation profiles, cost structures and system services (e.g., solar PV or small hydro). These benefits include: firm, dispatchable generation with high reliability; waste-to-energy capabilities that contribute to circular economy goals and emissions reductions; local environmental and economic co-benefits, such as reduced methane emissions from organic waste and support for agricultural and industrial sectors; and baseload or peak-shaving potential, enhancing grid stability and reducing curtailment risks for intermittent renewables.”

Capstone called for “bucketing” generation sources by technology types, to acknowledge those with capabilities such as peaking support, and by region, to reflect higher site costs in urban areas. “This will support reliability where it is often needed most,” it said.

The CHP Canadian Advisory Network said the projects IESO is seeking to re-contract originally were contracted through a program that was not technology agnostic, “which therefore makes it difficult to re-contract in a technology-agnostic manner.”

“For example, [combined heat and power] offers unique value (grid resiliency, improved overall system efficiency, etc.), which may come at a higher price,” it said.

It also requested the grid operator add a natural gas price hedging mechanism or “a more equitable sharing of risks, enabling more competitive bidding.”

The Ontario Clean Air Alliance countered that fossil fuel generation should be excluded from the program, noting that more than 70% of the gas used in Ontario power generation is imported from the U.S.

IESO’s 2025 Annual Planning Outlook predicts fossil gas will generate 25% of the province’s electricity in 2030, up from 4% in 2017. “It doesn’t make sense to increase our dependence on American gas when Canada’s sovereignty and economy are under attack by President Trump,” it said.

LDCs vs. Cooperatives: Transparency, Weighing Local Benefits

Another fault line is the role of LDCs.

CECC said the program should “reward meaningful community and indigenous ownership where genuine community equity and governance are embedded (while avoiding LDCs and private developers creating nominal co-ops or token partnerships solely for preferential treatment).”

IESO programs strategist Greg Bonser said the grid operator is “exploring” criteria other than price, “but we haven’t decided what those rated criteria might be at this point. For example, we might need to use them for tie breaking.”

The Electricity Distributors Association and Ontario Energy Association said LDCs “should lead re-contracting and new contracting.”

“The EDA and OEA believe that Ontario’s local distribution companies are best positioned to lead both re-contracting of existing distributed generation and the contracting of new DG resources,” they wrote. “LDCs have deep visibility into the local value of existing assets within their distribution networks and can engage directly with facility owners on key issues such as refurbishment needs, term lengths and future operational plans.”

CECC countered that its members’ ability to design new projects is hamstrung because they “mostly do not know if their connection points or local circuits could support an expansion or upgrade.”

“The IESO must work with LDCs to publish real-time or forecasted hosting capacity tools and ensure transparent, fair allocation mechanisms when multiple proponents seek access to the same line. Another suggestion is to establish standardized interconnection cost ranges across the province based on project size,” it said. “This would give community proponents clearer upfront cost expectations, reduce risk and uncertainty, and enable more predictable financial planning.”

Roles for Storage, Rooftop Solar, Virtual Net Metering

IESO also received appeals to expand the LGP program to include storage and smaller facilities such as rooftop solar.

Currently, new rooftop solar generation facilities between 1 kW and 1 MW are eligible for incentives through IESO’s electricity Demand-Side Management (eDSM) programs.

Improved technology could result in increased solar production from existing sites. “Given the realized and anticipated increases in the efficiency of solar panels, it is anticipated that we would plan to explore increases in generation capacity at all sites, even where rooftop size or land area constraints exist,” Community Energy Development (CED) Cooperative said in its written comments.

But many rooftop solar installations have been in place for nearly two decades, meaning the roofs may need repairs or replacement, adding costs to any re-contracting.

Bonser said the LGP would not offer additional compensation for storage or demand response. “However, if you can cost-effectively integrate those elements into your projects, you may be able to do so,” he said.

The Ontario Clean Air Alliance said “all environmentally responsible renewable energy projects,” including rooftop solar, should be eligible for the LGP, citing its study that found rooftop solar projects in Toronto could meet 50 to 80% of the city’s electricity needs.

CECC said IESO’s SaveOnEnergy program does not provide enough financial support for re-contracting solar facilities. It also said community-scale battery energy storage systems (BESS) should be included in the LGP.

“Cooperative ownership ensures that the benefits of storage — including grid services and cost savings — flow back to communities. This scale of storage is well suited for municipal feeders and can play a pivotal role in supporting local energy reliability projects (LERPs) and reducing the need for large-scale infrastructure upgrades, e.g. transmission lines. Bid evaluation should account for both location and time of generation and the advantages of community-scale BESS paired with solar can deliver.”

John Kirkwood, president of the Ottawa Renewable Energy Cooperative, said co-ops have had difficulty deploying storage because community-scale batteries are too small for participation in IESO “and LDCs can’t contract [with] us.”

“Batteries are part of the solution — we all know that — but it’s not very easy to add them to the grid,” he said.

Kirkwood also urged the grid operator to allow it to aggregate generation from its more than 1,100 members, many of which now have microFIT (feed-in tariff) contracts on individual meters, “which is challenging and costly for the province.”

“We’re willing to take it into consideration,” Bonser responded. “We want to make sure this program is as simple and cost effective as possible for all of the different parties involved, from suppliers such as yourself, who have members, for the LDCs and for the ISO. So, there are a few competing interests.”

Kirkwood and other cooperative representatives also called for co-ops to engage in virtual net metering, which would allow members to purchase electricity directly from cooperatively owned projects, even if they are not located on-site.

Allowing cooperative-owned projects to transition into community net-metering structures at the end of the current contract would allow them to continue, said CED Co-op, which has more than 100 FIT and microFIT contracts.

“If there are no reasonable contracting options available upon conclusion of the current contract, we would likely need to decommission the facility,” it said. “The current spot market rates do not appear that they would adequately exceed the costs of insurance, LDC fees, lease payments, and operations and maintenance expenses.”

Next Steps

IESO expects to report back to the Minister of Energy and Electrification on the LGP this summer and launch the program in 2026.

The grid operator will provide its responses to stakeholders’ feedback and present more details about the program designs in a webinar June 5.