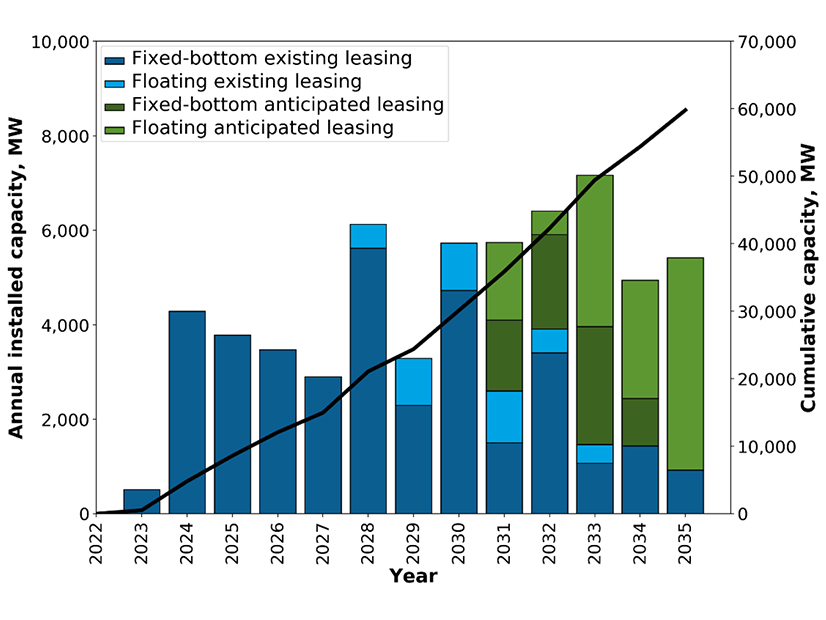

Reaching President Joe Biden’s goal of putting 30 GW of offshore wind off the Atlantic and Pacific coasts by 2030 will require a supply chain capable of producing more than 2,100 wind turbines and more than 6,800 miles of cables, according to a report released Monday by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL).

And most of the components for those turbines and cables must initially come from Europe, even though “it is unlikely that the international suppliers will have sufficient throughput to support construction of both European and U.S. offshore wind projects,” the report says.

“If a domestic supply chain is not developed in time, bottlenecks in the global supply chain will present a significant risk to achieving the national offshore wind energy target,” the report says.

But Ross Gould, vice president of supply chain development at the Business Network for Offshore Wind (BNOW) sees such supply chain challenges in terms of economic development and job growth. “We know that there is a wide range of opportunities for manufacturing companies in the U.S. to participate in the offshore wind supply chain,” said Gould, who worked with NREL on the report. “These offshore wind projects have the capability of creating tens of thousands of jobs.”

By 2028, offshore turbines using 100% American-made components could create up to 62,000 jobs, the report says, and even turbines with only 25% domestic content could generate about 15,500 jobs, the report says.

But the path to hitting any of those numbers, as laid out in the report, is daunting. For example, while plans are underway to build 11 new OSW manufacturing facilities that can produce major components, such as turbine blades and towers, major gaps exist in the domestic supply chain for the components those factories will need.

Offshore turbines contain around 8,000 components, many of them much larger than similar components for onshore turbines, Gould said.

Offshore turbine blades are as long as a football field, “significantly larger than their onshore relatives,” Gould said in an interview with NetZero Insider. “And so, while we have the capabilities to produce [blades] for onshore, those companies would need investment to upgrade their equipment, as well as potentially training [employees] on the new equipment.”

Other components are not being produced, or produced at scale, in the U.S., the report says. For example, the permanent magnets used in offshore turbine generators require rare-earth metals that are not mined and cannot, at present, be processed in the U.S.

Still another obstacle, the huge size of some offshore components may also mean they can’t be transported by highways, Gould said. They will need to be built near a body of water and port facilities large enough and deep enough for the wind turbine installation vessels (WTIVs) and other ships used to build and operate offshore projects ― which brings up additional supply chain gaps, the report says.

Of the 22 ports on the Atlantic Coast, the Portsmouth Marine Terminal in Virginia is the only one that currently has the capacity to accommodate WTIVs, the report says. Others, such as the New Bedford Marine Commerce Terminal are not large enough but can serve as marshalling areas, using smaller “feeder barges” to ferry components out to installation vessels.

Such workarounds may be less expensive, the report says, but “they also introduce additional risk and logistic complexity to transfer components from the barge to the WTIVs at sea.”

These installation vessels must also comply with the provisions of a 1920 federal law known as the Jones Act, which requires that ships carrying goods between U.S. ports be American built, owned and operated. The report estimates that at least five such ships will be needed, but only one is currently under construction, for Dominion Energy’s Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind project.

Estimated cost per WTIV ranges from $250 million to $500 million, the report says, and each ship could take up to three years to build.

The Next BOEM Auction

The study is the first of two reports NREL and other industry stakeholders, including BNOW, will be producing on the offshore wind supply chain. The first part is intended to set out the scope of the needed buildout and the challenges ahead, Gould said. The second, to be published later this year, will look more closely at the kinds of investments and other support that will be needed to reach Biden’s 30 GW goal.

The push for getting an offshore supply chain up and running as quickly as possible is being driven by the growing number of offshore projects in development up and down the East Coast.

In February, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) held a record-breaking auction for six offshore leases in the New York Bight, pulling in bids totaling $4.37 billion. If fully developed, the six auction sites could produce more than 19 million MWh of electricity per year, enough to power close to 2 million homes, based on BOEM’s estimate of 3 MW/sq km. (See Fierce Bidding Pushes NY Bight Auction to $4.37 Billion.)

The next BOEM auction, announced Friday, will be held on May 11, for two offshore leases in the Carolina Long Bay, off the coasts of North and South Carolina. According to the BOEM announcement, the two sites, totaling 110,091 acres, could produce up to 1.3 GW of energy, enough to power 500,000 homes. The final sales notice for the auction lists 16 eligible bidders, including Duke Energy Renewables, Ørsted North America and Shell New Energies.

With thousands of megawatts to be built in less than a decade, Matt Shields, senior offshore wind analyst at NREL, estimates that two or three manufacturing plants will be needed for each major offshore wind component, such as blades and cables. Costs per facility could range from $200 million to as high as $900 million, he said.

“These figures typically don’t include additional investments in port capabilities to support these big facilities,” Shields said in an email to NetZero Insider. “We can safely say that, if we do build all these facilities, it will be in the billions of dollars and will require a mix of public [and] private investment.”

While the current report does not address policy, Shields said, “There are a lot of nuances about what exactly is needed. … The most important thing is certainty about projects actually getting built so that OEMs can have low-risk return on investment.”