A new analysis details some of the job growth and employment demographics connected to the proliferation of renewable energy in recent years.

It is based on data that predates the second term of President Donald Trump, and his attempts to rapidly reconfigure the energy industry. The pattern highlighted by the authors — that the renewables workforce varies significantly between regions — is likely to remain relevant, but the observation that the wind and solar workforce is growing as a percentage of the energy workforce may change.

The analysis was performed by one former and two current staff members at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, which announced the results Aug. 26 with the caveat that the views expressed are the authors’ and not attributable to the Federal Reserve System or its Dallas branch.

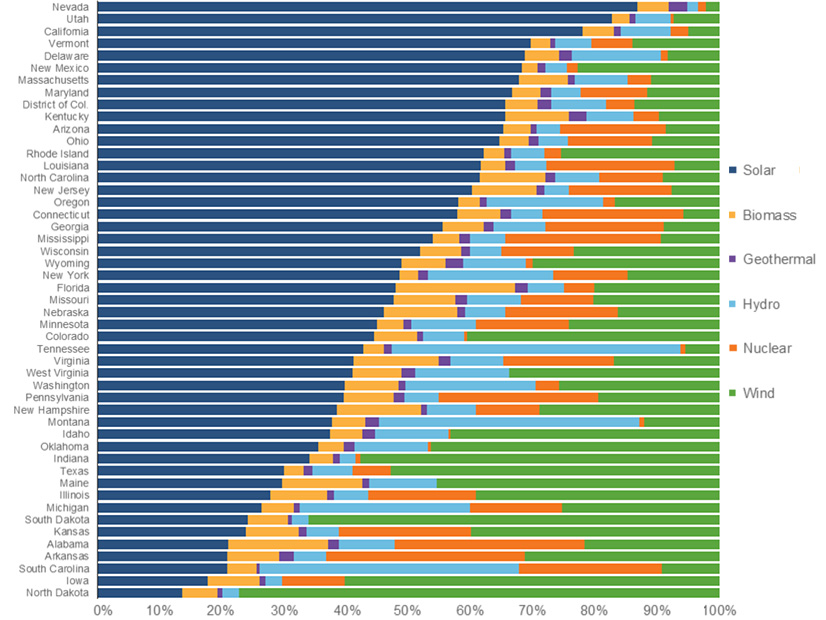

Wind and solar account for the majority of renewable energy jobs in most states, the authors write, but the percentage of each can differ sharply from one state to the next.

Nevada is at one end of the scale, with solar accounting for 87% of the renewable energy workforce and wind just 2% — the largest and smallest percentages in any of the contiguous 48 states.

North Dakota is at the opposite end, with solar accounting for 14% and wind 77% — the smallest and largest percentages within the Lower 48.

The reasons are straightforward: Nevada has few wind turbines and North Dakota has little commercial solar capacity.

The authors note, however, that while wind and hydropower energy development (and jobs) tend to happen where there is strong, steady wind or where large amounts of water flow over suitable topography, photovoltaic projects are not as clearly correlated to the strongest solar irradiance.

State-level factors such as tax credits and energy standards produce pockets of solar development where sunlight is not necessarily strongest.

Some of these employment trends are likely in line for changes.

The U.S. Energy Information Administration reported Aug. 20 that solar, storage and wind development already in the pipeline is expected to boost overall energy development to a new annual record in 2025. (See U.S. Could Gain 33 GW of Solar, 18 GW of Storage in 2025.)

But BloombergNEF reported Aug. 26 that new renewable energy investment announced in the U.S. in the first half of 2025 dropped $20.5 billion or 36% from the same period in 2024, due to the Trump administration’s energy policy changes and tariff threats.

The employment report was written by Garrett Golding, an assistant vice president for energy programs at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas; Xiaohan Zhang, a senior research economist; and Claire Jeffress, formerly a research analyst there.

They note the importance of accurate employment statistics in targeting workforce development efforts for what is expected to be a period of strong growth for multiple sectors in the energy industry: “Though employment in these sectors is growing faster than the rest of the labor force, the number of qualified workers hasn’t kept pace.”

But they also note the potential pitfalls in trying to compile such data.

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, for example, counted just 8,000 wind industry jobs nationwide in 2022, while the U.S. Department of Energy tallied 125,000.

This is because the BLS industry classification system predates wide use of wind and solar generation; there are nuances within the jobs themselves that can lead to misclassification; and DOE includes jobs in industries closely related to power generation, but BLS does not.

In recognition of this, the DOE published the first U.S. Energy and Employment Report in 2016. The most recent edition, in August 2024, filled more than 200 pages with statistics and also served as a report card of sorts for the policies of the Biden/Harris administration as the presidential election neared. (See DOE Details Strong Job Growth in Clean Energy.)