A relatively small project aiming to increase gas pipeline capacity into New England is raising larger underlying questions about how the region will balance gas reliability and affordability with longer-term efforts to transition away from natural gas.

Enbridge’s proposed expansion of its Algonquin pipeline, announced in September, has an estimated cost of $300 million and would increase the pipeline’s capacity into the region by about 2.5%. The company aims to complete the project in 2029.

Algonquin has announced it has reached agreements with seven utilities for the added capacity, including Rhode Island Energy and subsidiaries of Eversource Energy, which submitted a pair of 10-year supply delivery contracts associated with the project to the Massachusetts Department of Public Utilities in September.

Eversource said the contracts are needed to “address a reliability risk related to operational changes” instituted by Algonquin in 2019 reducing flexibility in nominations that previously allowed the company to nominate more than their contracted delivery entitlements in certain areas during cold-weather periods.

The company also said the added capacity would eliminate its “need to extend the G-Lateral supply portion” of its contracts with the Everett Marine Terminal (EMT), a major LNG import facility located north of Boston and owned by Constellation Energy.

By replacing LNG supply with pipeline gas, the project would reduce total gas costs for customers of two subsidiaries by about 5% and 1%, the company said.

“Without the proposed agreement, [Eversource] and its customers risk exposure to inadequate and unreliable supply and high city-gate pricing during peak days for customers served by Algonquin’s G-System, and would need [to] enter into negotiations with Constellation … for gas supplies to serve the G-Lateral from EMT after 2030,” Eversource argued.

However, environmental nonprofits argue the Algonquin expansion project would not eliminate the region’s overall need for the Everett terminal and instead likely would shift its costs to other customers.

In Eversource’s filing, the company appears to acknowledge the Algonquin expansion would not eliminate the region’s reliance on Everett, writing that the agreement would “not resolve regional dependence on natural gas from peaking resources” and adding that the terminal “provides a unique and critical energy resource in New England.”

In joint comments submitted earlier in October, the Acadia Center and the Conservation Law Foundation (CLF) wrote that the DPU must consider how the contracts “will impact not only Eversource customers, but also other gas customers, including National Grid and Unitil, whose contracts with Constellation mirror [Eversource’s].”

The Role of Everett

Until spring 2024, Everett’s main customer was Mystic Generating Station, a 1,413-MW, Constellation-owned combined cycle plant located nearby.

In the months leading up to Mystic’s retirement, local distribution companies owned by National Grid, Eversource and Unitil reached agreements with Constellation to keep Everett open through 2030. The contracts were necessary to provide adequate supply and preserve system reliability, the utilities wrote (DPU 24-25-B, et al.). (See Massachusetts DPU Approves Everett LNG Contracts.)

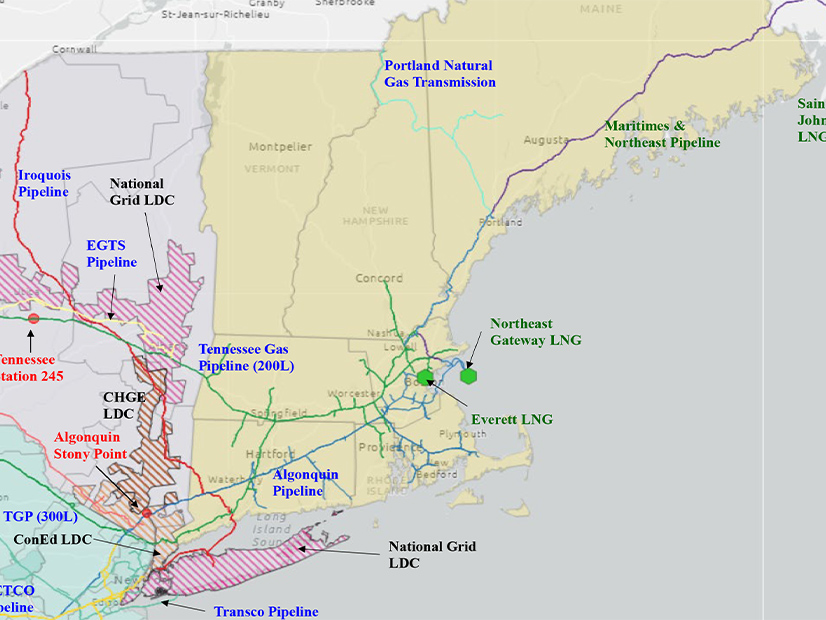

Everett “is ideally located in the heart of the market” at the back end of the Tennessee and Algonquin pipelines, Richard Levitan, president of the energy consulting firm Levitan & Associates, explained in an interview with RTO Insider.

Levitan stressed the importance of local deliverability to the system. LNG from Everett and Repsol’s Saint John LNG terminal in New Brunswick provides the “oomph to energize the network of pipelines serving gas utilities and generators in New England during cold snaps or some type of outage contingency along the mainlines serving New England,” he said.

He added that Everett “is the primary hub of truck-transported LNG to refill the dozens of satellite LNG tanks in New England that bolster pressure behind the pipeline citygates,” a role that cannot be replicated by the Saint John terminal.

Levitan noted that the Algonquin expansion project “is small in relation to the daily output” of both the Everett and Saint John facilities when the terminals are performing. He emphasized that, unlike conventional forward-haul service from the Gulf Coast or Marcellus Shale, LNG facilities provide operational and scheduling flexibility by enabling injections into the back end of the gas systems.

“When these import facilities are dispatching during cold weather events, it’s beneficial to the bulk electric generation market, and also to the LDCs, who generally look to supplement their pressures via displacement services when there are harsh operating conditions,” he said.

While utilities and gas generators rely on Everett to add supply downstream of New England’s gas constraint during peak periods and to provide backup supply during pipeline outages, the facility again faces an uncertain future after its contracts with the utilities expire in 2030.

The contracts are costly for ratepayers; Eversource estimated in 2024 they would increase rates by 5 to 7% for customers of one subsidiary and 2 to 3% for customers of another. Long-term reliance on Everett also likely would run contrary to Massachusetts’ longer-term efforts to move away from natural gas to reach net-zero emissions by 2050.

When approving the contracts, the DPU required the gas companies to “make significant strides to reduce or eliminate their reliance on EMT in the near-term” and directed them to “fully investigate all possible alternatives to EMT … including energy efficiency, strategic electrification and networked geothermal projects and, to the extent feasible, to coordinate their planning efforts.”

The order also required annual reports about the utilities’ efforts to reduce reliance on the facility, and in fall 2024, the Massachusetts Office of Energy Transformation established a working group focused on moving away from Everett.

Who Pays?

While the pace and trajectory of the gas transition in Massachusetts likely will determine the long-term demand for existing and new gas infrastructure, the fate of Everett, as well as the fate of gas pipeline expansion projects into the region, may be defined in large part by questions about funding.

The Algonquin expansion project essentially is a significantly scaled back version of Enbridge’s previously introduced “Project Maple,” which proposed to increase Algonquin’s capacity by up to 250,000 Dth/d at the eastern end of the pipeline. (See Enbridge Announces Project to Increase Northeast Pipeline Capacity.)

The smaller size of the updated 75,000 Dth/d expansion project appears to reflect the challenges of finding long-term customers for the increased capacity.

“Following the conclusion of the Project Maple open season in November of 2023, we decided to right-size Project Maple to better meet our customers’ specific needs, with a smart, targeted enhancement,” Enbridge spokesperson Melissa Sherburne said in a statement.

While New England relies heavily on gas generation, which hit a record high in 2024, generators’ access to gas is constrained during cold weather when heating demand is high. (See New England Gas Generation Hit a Record High in 2024.) Generators historically have been reluctant to take on long-term gas contracts, largely because of the financial risks associated with assuming these commitments.

Electric ratepayers also appear unlikely to finance new infrastructure; a 2016 ruling by the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court prohibits charging electric customers for the costs of new pipelines.

Meanwhile, residential, commercial and industrial gas demand has been relatively stagnant in recent years, and, seeking to decarbonize, Massachusetts lawmakers and regulators have taken significant steps to slow the expansion of the system and push gas customers to electrify. (See Outgoing Mass. DPU Chair Van Nostrand Discusses Gas Transition.)

“As far as who would pay [for Everett] in 2030 if Eversource is not a contracted party, it would have to be other LDCs, conceivably generators if we see the evolution of price signals under accreditation taking form, and marketers,” Levitan said.

As ISO-NE overhauls how it accredits resources in the capacity market, the RTO is poised to increase incentives for resources to procure firm fuel. However, the extent to which this will cause generators to enter long-term firm contracts is unclear.

In ISO-NE’s Capacity Auction Reform project to date, “we’re not seeing the evolution of accreditation principles that will clearly induce the generators to line up firm rights, so I don’t think at this moment in time we can reasonably expect the generators as a cohort group in New England to foot the bill for a major new pipeline push,” Levitan said.

Everett’s funding challenges mirror the challenges faced by any large pipeline project into the region, which are complicated by the state’s push to decarbonize.

Climate and consumer advocates have argued that Massachusetts must be careful not to make long-term investments in the gas system that end up becoming stranded assets. Some advocates see the 10-year duration of Eversource’s proposed Algonquin expansion contracts as reflecting uncertainty about long-term gas demand on the distribution system.

Joe LaRusso, senior advocate at the Acadia Center, said he’s skeptical gas utilities will experience enough new demand to support a “a substantial increase in gas capacity into the region.” He added that pipeline companies looking to build major new projects “can’t find the off-takers for this stuff; they can’t get it built.”

Acadia and CLF’s comments on Eversource’s contracts with Enbridge focus on Eversource’s underlying assumptions about its forecasted gas demand between 2029 and 2039. The groups highlight data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration indicating that overall residential, commercial and industrial gas demand in Massachusetts declined between 2019 and 2024.

They wrote that Eversource has provided “no basis to determine what their gas requirement will be over the term of the proposed contracts,” nor data on how “declines in statewide gas consumption in those sectors might ultimately influence either their overall consumption or their design day supply.”

In Eversource’s initial petition, the company wrote it “has not identified other viable alternatives to the proposed agreement,” adding that “the pace, scale and scope of energy efficiency and electrification would be insufficient to address the load requirements for the G-Lateral.”

Decarbonization Challenges

As utilities and regulators work to ensure the reliability of the state’s gas system, an inherent tension exists between investments to bolster the system and efforts to decarbonize.

While the gas industry frequently points to the reduction in carbon dioxide emissions associated with burning natural gas instead of coal or oil, methane is a key driver of manmade climate change and has particularly severe warming effects when evaluated over a more immediate time frame.

In a landmark order in late 2023, the DPU ruled that the decarbonization of the state’s gas system should center around electrification and emphasized the need for a managed transition away from gas and gas infrastructure (DPU 20-80-B). (See Massachusetts Moves to Limit New Gas Infrastructure.)

The state remains in the early stages of implementing this new regulatory framework, and in recent months, utilities and climate advocates have clashed over the LDCs’ legal obligation to serve customers, and whether the utilities could require customers to give up their gas service when decommissioning a section of pipe.

If successful, the electrification push would drive a substantial increase in power demand, which could cause continued growth or reliance on gas generation. While there is almost no proposed new gas generation in the ISO-NE queue, the challenges experienced in the offshore wind industry create significant questions about how the region will meet this growing demand.

“The demise, temporary or not, of offshore wind bodes poorly for certain environmental goals to be achieved in the early and mid-2030s if electrification gets the kind of traction that regional policymakers envision,” Levitan said. “There could be much more work burden on the existing thermal fleet to accommodate a pathway that is all about switching over from a summer to winter peak because of electrification.”

But for grassroots climate activists in Massachusetts, any efforts to expand natural gas infrastructure into the state are a step in the wrong direction.

“The answer is not, and never has been, keeping on with the gas system,” said Cathy Kristofferson, a longtime environmental activist in the state who co-founded the Massachusetts Pipe Line Awareness Network. “Everyone’s trying to figure out the affordability angle of it all, and for us, adding a bunch more steel in the ground is never affordable.”

Rosemary Wessel, an activist with the Berkshire Environmental Action Team, said Enbridge’s recent Algonquin proposal appears to be part of a strategy focused on incremental expansions to increase gas capacity into the region.

At an industry conference in September, Mike Dirrane, director of Northeast marketing at Enbridge, speculated that there may be an additional project after the current Algonquin expansion effort “to meet additional needs further down the road.” (See Gas Industry Sees Political Opportunity in New England.)

“They’re segmenting a larger expansion into small projects,” Wessel said. “We should not be serving that by approving contracts for more gas.”