As someone who spent close to two decades as a state regulator, FERC Commissioner Mark Christie said he can’t help but look at federal administrative issues through a local lens.

Christie, who joined the commission in January after 17 years with the Virginia State Corporation Commission (SCC), told attendees of the Organization of PJM States Inc.’s (OPSI) virtual annual meeting this week that his tenure as a state regulator and past OPSI president taught him “how much I do not know” about regulatory issues.

No one understands better the challenges, problems and opportunities of utility regulation on a local basis than state commissioners, Christie said, calling it a “practical perspective” that has allowed him to realize each state has different challenges on reliability issues, costs of projects and market development.

Christie said in his keynote address that it’s important as a FERC commissioner to be sensitive to the differences between states and regions of the country.

“Utility regulators in each state know more than I’ll ever know or anybody here at FERC will ever know,” Christie said. “That’s exactly how federalism works.”

Federal vs. Local Control

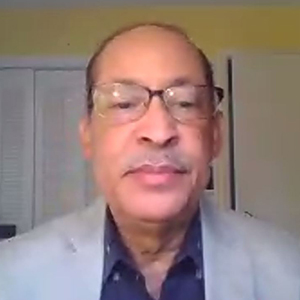

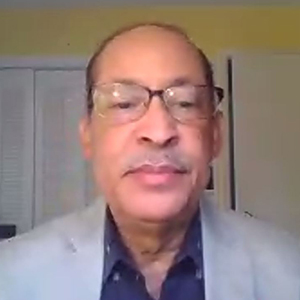

Harold Gray, OPSI | OPSI

Harold Gray, OPSI | OPSIDelaware Public Service Commissioner and current OPSI President Harold Gray asked Christie his impression of the infrastructure legislation pending in Congress and if any new rules and regulations in it could create bigger challenges for FERC.

Christie said the “devil’s always in the details” in understanding the impact of legislation, and he still wasn’t sure how the bill will ultimately pan out. He said his time in Virginia taught him to expect the unexpected when it came to legislation, but that whatever passes must be implemented regardless of whether regulators think it’s a good idea or not.

One idea Christie said he’s “not a fan” of is the concept of the federal bureaucracy overriding state transmission siting. He said there’s been a big push lately among some lawmakers and stakeholders to give the federal government override authority because of a perceived notion that states are standing in the way of building new transmission and developing the grid of the future.

“The state regulators are not the obstacle to siting large regional transmission lines,” Christie said.

As an example, Christie cited the “very controversial” Trans-Allegheny Interstate Line (TrAIL) project, a 165-mile, 500-kV transmission line that crossed Pennsylvania, West Virginia and Virginia beginning in 2008. He said TrAIL remains the largest regional line in PJM’s portfolio.

Christie said he remembers sitting in meetings across Virginia as residents expressed their displeasure with the project, but the developers were ultimately able to make their case for its need.

“Need was proven in the TrAIL case, and it got built,” Christie said. “If you can prove need, I’m optimistic that they will get built. But you’ve got to go into a state regulator and prove that need.”

Christie said he hears rhetoric from Congress members and other interested stakeholders that all it takes is one state official to “kill a vitally needed power line,” but he disagrees: It takes a commission to decide after having a quasi-judicial proceeding where evidence is presented.

Federal siting authority could also prove to be detrimental, creating massive political backlash to the federal government stepping in to decide local issues, he said.

The TrAIL project wasn’t a greenfield line requiring eminent domain, but instead used existing rights of way, and it still created controversy. Greenfield projects approved by a federal agency could prove to be even more controversial, he said.

“You seriously think that there’s not going to be a huge political blowback having a federal official just order something to be built?” Christie asked.