The focus on technology in many roadmaps for the transition to a carbon-free economy ignores the inevitable social impacts of the changes, the National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM) said in a report last week.

To succeed, the report argues, the U.S. transition must incorporate “the development and maintenance of a strong social contract.”

That focus on social impacts is what differentiates “Accelerating Decarbonization of the U.S. Energy System” from other reports issued after the 2020 election, said Princeton University’s Stephen W. Pacala, who led the committee of experts who wrote the report.

“Because even if we have cheap technologies, even if we succeed in innovation, we won’t be able to sustain the pace of the transition and the longevity of the marathon all the way to 2050 without delivering concrete benefits to people in the near term and mitigating the kinds of impacts that could derail the transition in the long term,” Pacala said during a Feb. 2 webinar on the report.

Pacala said that while the report was compatible with President Biden’s aggressive climate action plan, it was developed independently. In particular, Pacala and his co-authors called for the creation of several federal entities that would tackle both the benefits and mitigation needed for a nationwide commitment to decarbonization:

- a national transition task force to provide a comprehensive view of communities and industrial sectors at risk and the kind of help they will need;

- a White House Office of Equitable Energy Transitions to establish targets and monitor progress of federal programs working for a just transition and provide yearly evaluations and progress reports;

- an independent national transition corporation to mitigate the impacts of the transition, for example, by supporting communities that have lost a critical employer; and

- a federal green bank, initially financed at $30 billion, to invest in the development of zero-carbon technologies and infrastructure that are currently being tested and piloted but are not yet cost-competitive.

On Wednesday, Democrats reintroduced legislation that would create a $100 billion green bank, which the sponsors say would spur nearly $400 billion in private co-investments.

Last month, Biden issued an executive order establishing an Interagency Working Group on Coal and Power Plant Communities and Economic Revitalization, to be co-chaired by National Climate Adviser Gina McCarthy and Brian Deese, director of the National Economic Council. The working group will direct federal agencies to coordinate investments and other efforts to assist coal, oil and natural gas, and power plant communities.

The order also includes a “Justice40 Initiative,” requiring the chair of the Council on Environmental Quality, the director of the Office of Management and Budget and the national climate adviser to publish within 120 days “recommendations on how certain federal investments might be made toward a goal that 40% of the overall benefits flow to disadvantaged communities.” (See Biden Signs Sweeping Climate Orders.)

The National Academies’ report also recommends increased funding for research initiatives aimed at “modeling, data collection and data analysis that would support regional, state and local decision-making,” said Clark Miller, a professor at Arizona State University.

“It includes funding for the development of regional coordination centers that would help mayors and governors and other regional actors work together to plan aspects of the transition that cut across state lines and urban-rural lines,” Miller said.

No Single Answer

At the same time, local decision-making must also move beyond telling under-represented communities to come to meetings and provide input, the report says.

“The current state of public participation is woefully inadequate to the task,” said Danielle Deane-Ryan, senior adviser to the nonprofit Libra Foundation. She sees a major role for the White House Office of Equitable Energy Transitions in identifying best practices for improving community involvement in decision-making.

Similarly, “equity indicators” need to be built into funding initiatives both at the federal green bank and the Department of Energy, Deane-Ryan said. Another role for green banks should be providing low-income communities with ways to access renewable energy, as well as creating more options for displaced fossil fuel workers, said Julia Haggerty of Montana State University.

“Many people are curious about what individual fossil fuel workers are going be doing in the future, and there is no one single answer,” Haggerty said. Not all will be able to retrain for jobs in renewable energy or start new businesses and may need direct assistance for housing and lost income, she said.

Acknowledging Uncertainty

While integrating equity and social impacts into all its recommendations, the NASEM report does not skimp on technology and policy issues. For example, it calls for a national carbon tax starting at $40/ton of carbon dioxide and rising by 5% a year, with the goal of doubling the tax over 14 years.

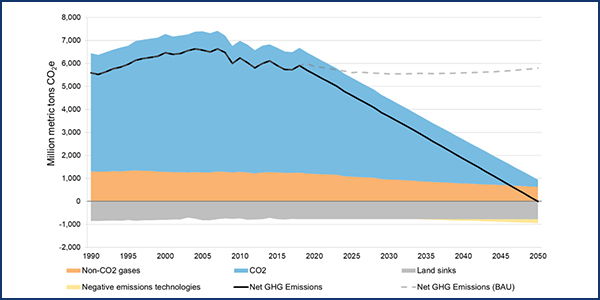

If implemented, Pacala estimated the tax could raise $2 trillion in revenue by 2030 to help fund the transition. He also emphasized that because of the ever decreasing costs of wind and solar, the transition to net-zero emissions will ― after initial upfront investments ― cost less than the country has spent on energy in the past 30 years.

The report also argues that while the next decade requires accelerated ramping up of renewables, the path forward must acknowledge the “uncertainty about the final makeup of the energy system,” Pacala said.

“We need the same actions whether or not we’re shooting for a 100% renewable system in the end, or a system that retains strong elements of decarbonized fossil fuel use and nuclear electricity,” he said.

Such uncertainty may be a constant. The report notes that major parts of the U.S. energy infrastructure have life cycles longer than the 30-year horizon to 2050. The report calls for a tripling of R&D funding to ensure that as long-lived infrastructure is replaced, low- or no-carbon technologies will be commercialized and competitive, especially for hard-to-decarbonize sectors such as aviation and chemical manufacturing.

The goal, Pacala said, is to make sure that when infrastructure is replaced, “the no-brainer, economic self-interested decision is to invest in technology that is consistent with a net-zero transition.”