The Desert Southwest (DSW) region is at risk of failing to meet loads during its peak hour this year even under the most optimistic assumptions — with risks rising to seven hours next year — according to a new report from WECC.

That analysis follows on the December release of WECC’s Western Assessment for Resource Adequacy, which found that the Western Interconnection could experience one to eight hours in 2021 in which some of its subregions fail to meet the one-day-in-10-years (ODITY) threshold for resource adequacy. (See Western RA Planning Must Change, WECC Says.)

Potential RA shortfalls have been a growing concern in the West as states have mandated the closure of fossil fuel generators while requiring buildout of variable renewable resources. The issue took on new urgency last August when an extended and severe heat wave prompted rolling blackouts in California and grid emergencies in neighboring regions.

“In the heat wave of last year … we just didn’t have enough reserve margin going into those hours. The variability hit us, with the high demand throughout all of the interconnection,” WECC Manager of Performance Analysis Matt Elkins said Tuesday during a webinar to discuss the report.

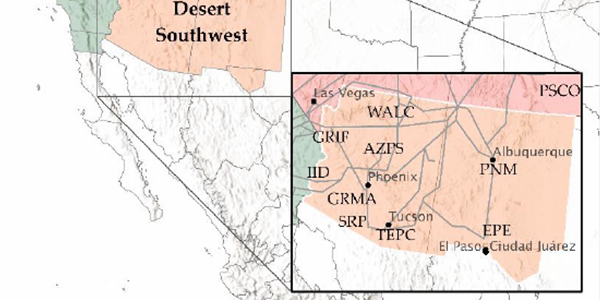

The report focuses on an area that largely covers Arizona and New Mexico but also extends into the service territories of the Imperial Irrigation District in Southern California and El Paso Electric in West Texas. Over the next month, WECC will release additional reports for California and Mexico and the vast area served by the Northwest Power Pool.

In its assessment, WECC applied two scenarios to the five subregions to examine a broad range of future resource possibilities and factor in known and expected resource retirements. Scenario 1 — referred to as the “standalone” scenario — assumes that each subregion will be responsible for meeting its load with internal resources, while Scenario 2 allows for imports.

WECC then overlaid each scenario with three variations of resource availability. Variation 1 includes all resources currently in service and expected to be operable in future forecasts. Variation 2 includes existing resources and those under construction and expected to run in the forecast year (Tier 1 resources). Variation 3 — which represents the most “optimistic” assumptions — includes existing and Tier 1 resources as well as those currently in licensing or siting phases but not yet under construction (Tier 2).

‘We Just Can’t Use Fixed’

WECC found that demand in the DSW subregion is expected to peak in early July around 25,700 MW, although there is a 5% probability the peak could hit 29,100, equating to a 13% load forecast uncertainty. The subregion’s coincident peak is expected to occur at 4 p.m. that day, with the lowest demand occurring at 4 a.m.

“Overall, the DSW subregion should expect a 100% ramp, or 12,800 MW, from the lowest to the highest demand hour of the peak demand day,” the report said.

The analysis finds that the DSW should have about 29,300 MW of resources available to meet the expected peak demand, but based on historical analysis, there is a 5% probability that only 24,300 MW will show up, requiring “significant imports” to provide relief.

A standalone situation would translate into chronic problems for the DSW this year. Under Scenario 1 (no imports), the subregion is at risk of not meeting the ODITY threshold for 415 hours, translating into 624 MW of unserved demand for each hour.

While that scenario is unlikely given trading patterns in the West, even under the most optimistic assumptions (Scenario 2, Variation 3), the DSW still confronts the potential of falling short of the threshold for one hour this year, WECC found. In 2022, at-risk hours increase to seven under that situation, and rise even more sharply under a scenario that assumes imports plus only Tier 1 resources (14 hours) and imports with only existing resources (44 hours).

While WECC said imports reduce the probability that the DSW will become resource inadequate, it also warned that the growing variability in supply and demand across the Western Interconnection “increases the risk that imports may not be available when needed.”

The problem becomes especially acute with the increased adoption of solar resources, which all fall off the system around the same time in the evening, prompting the need for sharp ramps from other resources.

“One of the things we need to realize, and I think the heat wave event was a prime example, is that if variability hits everybody at the same time, there could be less available out there for assistance for the Desert Southwest,” Elkins said.

The increasing bent toward system variability means that Western utilities should revisit the practice of maintaining fixed planning reserve margins (PRMs) on an annual or seasonal basis, and instead consider dynamic margins to fit hourly needs, WECC contended in its December assessment.

Elkins raised that point again Tuesday, saying the need for dynamic PRMs becomes even more evident during the shoulder seasons of spring and fall, when demand is even more variable than during the peak seasons. Maintaining the standard of 15% margins used in much of the West just won’t suffice, he said.

“When you get into the springtime or in the fall and you’re doing planned maintenance … if you’re taking resources out, you’ve got to understand this is a very variable time in the system, so [you] need to make sure [you] hold more than 15%,” Elkins sad.

“With variability growing in the system, the [PRM] percentage has to be variable. We just can’t use fixed,” he said.