By Rich Heidorn Jr.

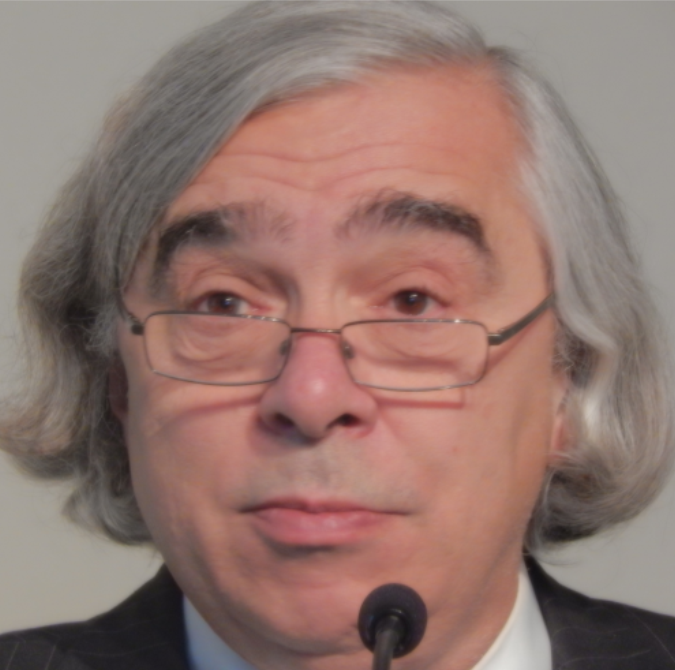

NEW YORK — Energy Secretary Ernest Moniz traveled to New York last week to get Wall Street’s perspective on challenges to financing electric transmission and other energy infrastructure.

The response? Do more to get the state and federal governments aligned on policy and regulation. With Congress incapable of passing any legislation and coal states alienated by the Obama Administration’s carbon policies, that’s a tall order indeed. But since Moniz asked, they told him.

The session at New York University was the final public hearing outside Washington this year in the Obama Administration’s Quadrennial Energy Review. President Obama announced the initiative – an effort to coordinate energy policies among all federal agencies — in January.

Moniz said the administration will be seeking ways it can use its existing authority rather than seeking new legislation.

He cited the Energy Department’s $1 million investment to help New Jersey Transit’s train system develop a microgrid, a project prompted by the outages caused by Superstorm Sandy. “It’s trying to look for leverage points even where we don’t have direct authority,” Moniz said.

A sampling of comments:

Despite “a surplus of capital today that is trying to get deployed,” said Kerri Fox, North American head of structured finance for BBVA, “there’s been a dearth of projects that are structured in a way that can be financed.” A lack of long-term contracts has made it difficult to obtain financing for transmission and storage projects, she said.

Fox said public-private partnerships (P3s), which have helped build infrastructure in Canada, could help finance interstate transmission. Alternatively, the administration could develop a “best practice” P3 that states could adopt.

“I think one of the problems in this country has been the piecemeal approach,” Fox said. “As we’ve done financings in various states it’s always different. I think the developers have a hard time knowing for sure that if they invest the money that there will actually be a transaction that comes out of it. My watch word would be simplicity and coordination across the states.”

John Lange, global head of Barclays Capital’s power and utilities group, agreed. “It’s pretty tough with 50 states, the [Department of Energy], the [Environmental Protection Agency], the [Federal Energy Regulatory Commission], for investors to understand where things are headed. If you can keep things coordinated and transparent … that will keep the cost of capital as low as possible.

“The market remains extremely global in terms of competition for capital. There is a lot of capital out there but everyone on the power utility and infrastructure side is comparing jurisdictions. They’re comparing regulatory regimes; they’re chasing the best returns.”

Lange also said many are skeptical of investing in renewables. “Costs [of renewables] have come down dramatically. But the reality is … a lot of the energy is coming from the traditional way — utility assets. We want to make sure we don’t get burned by putting money into those [investments] and not getting the right rate of return for the risk we thought we were taking.”

Stephen Zucchet, senior vice president of Borealis Infrastructure, an arm of the Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement System (OMERS), cited as a success story Texas’ Competitive Renewable Energy Zone (CREZ).

Seven transmission and distribution utilities are building the project, which will be able to carry 18,456 MW of wind power from West Texas to the state’s urban areas. “Today you have a $5 billion project that’s well on its way to being completed,” he said. “[It could be] a template.”

Humayun Tai, a partner in McKinsey’s energy practice, said as much as 25% of RTO interconnections are for remote renewables. “You have load pockets and you have investment pockets. Over time as those separate, meaning load grows in an area you didn’t expect, you get congestion. And we are behind on congestion spending.”