The U.S. now can manufacture enough solar panels to meet domestic demand but still must import most of the core components ― the solar cells and the silicon wafers used to make them ― according to the latest figures from the Solar Energy Industries Association.

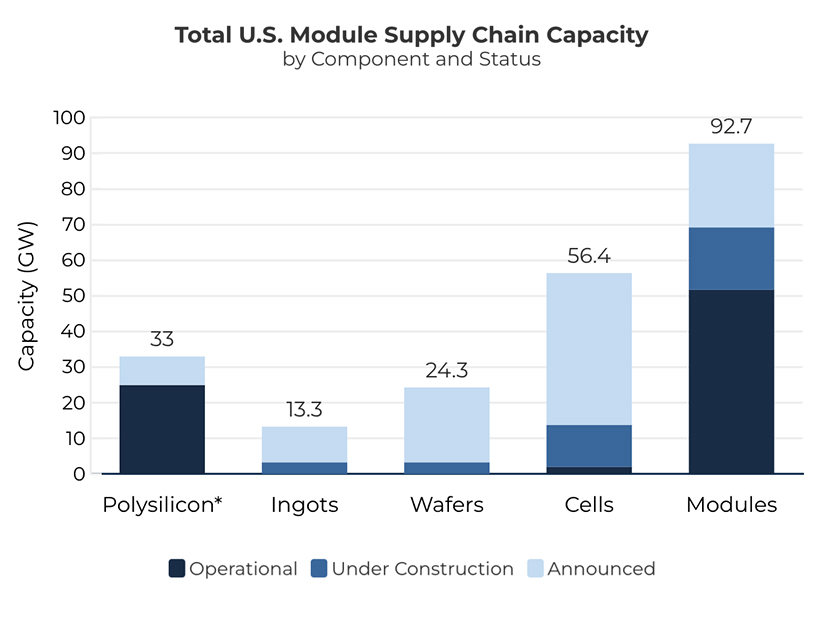

The U.S. has enough solar panel manufacturing capacity to produce more than 51 GW of panels per year, with an additional 17.5 GW under construction and 23.5 GW of additional capacity announced. The industry installed 40.5 GW of solar in 2024, according to a separate year-end report from SEIA.

The upstream supply chain, however, lags far behind. The nation has only 2 GW of solar cell manufacturing online versus 42.6 GW announced and 11.8 GW under construction. Production of silicon ingots and wafers has yet to go online, with only 3.3 GW under construction.

SEIA is putting a positive spin on the disconnect, noting that it originally set a 50 GW target for panel manufacturing in 2020, expecting to hit that goal by 2030. Reaching and exceeding the benchmark five years ahead of schedule “is a testament to what we can achieve with smart, business-friendly public policies in place,” CEO Abigail Ross Hopper said in a Feb. 4 press release.

“The U.S. is now the third-largest module producer in the world because of these policy actions,” Hopper said. “This milestone not only marks progress for the solar industry but reinforces the essential role energy policies play in building up the domestic manufacturing industry that American workers and their families rely on.”

Without actually naming the law, Hopper is referring to the clean energy tax credits and incentives contained in former President Joe Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act. SEIA specifically advocated for the law’s advanced manufacturing production tax credit, applicable to solar manufacturing, and bonus incentives for solar projects that use products made in the U.S., according to the press release.

The organization also successfully pushed for a 25% investment tax credit for domestic production of solar wafers and ingots, contained in the CHIPS and Science Act, which like the IRA was passed in 2022.

SEIA frames the lag in cell and wafer manufacturing as the result of “sequencing the build-out of a domestic solar supply chain. Establishing production of downstream components like modules ensures there is sufficient demand for upstream manufacturing,” according to the press release.

Tariff-proof Chinese Wafers?

Since President Donald Trump won the election in November, SEIA has been focused on protecting solar’s federal tax credits by positioning the industry as a critical part of Trump’s vision for U.S. energy dominance and independence, as well as a major source of the clean, affordable power needed to meet growing demand from data centers.

The organization also continues to tout the private investment and jobs that solar manufacturing has brought to Republican states and congressional districts. By SEIA’s count, new or planned solar manufacturing facilities are located in 23 states with Republican governors and 122 districts with Republican representatives in Congress, versus 20 states and 90 districts with Democratic leaders and lawmakers.

The industry’s weak spot, however, could be its continued dependence on imported cells and wafers. Private investments in new U.S. facilities could be at risk if congressional Republicans take steps to reduce or roll back clean energy tax credits and other incentives as part of their plans to extend the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.

First published by Politico, a recently circulated short list of potential budget cuts Republicans are considering includes discontinuing $300 billion in clean energy funding from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and an additional $56 billion in grants from the IRA.

In an email to NetZero Insider, Elissa Pierce, a research analyst at Wood Mackenzie, notes that in 2024, “62.5% of US cell imports came from Cambodia, Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam,” the four nations subject to antidumping and countervailing duty tariffs imposed by the Commerce Department in 2024.

An investigation by the International Trade Commission found that companies in those countries were using Chinese components in their products, while seeking to circumvent existing U.S. tariffs on Chinese solar cells and panels.

Pierce expects the percentage of solar cell imports from the four nations will decrease in 2025, with imports from Indonesia, Laos and South Korea rising.

More to the point, she said, prospective cell manufacturers in the U.S. could still import wafers and ingots from China — even with increased tariffs — because “Chinese wafers are so cheap that this isn’t very impactful. Some of the cell manufacturers coming online this year have stated that they will get wafers from Southeast Asia.”

The industry recently celebrated the opening of a new U.S.-owned cell manufacturer, ES Foundry, in South Carolina, Christian Roselund, senior policy analyst at Clean Energy Associates, wrote on LinkedIn. But he cautioned that “U.S. solar manufacturing is a long way from being able to meet the demands of our internal market at the cell level.”

Erecting trade barriers and cutting federal incentives “will set back U.S. solar manufacturing, not advance it,” he said.