A new analysis concludes there will not be enough computer chips produced in the entire world to supply the data centers some sources predict will be built just in the United States.

The report is the latest of many doubts raised about sky-high expectations for data center load growth, and it warns about the huge cost of overbuilding the grid to meet the highest 2030 projections.

The projections are varied, but most are large, and they are driving policy-making discussions.

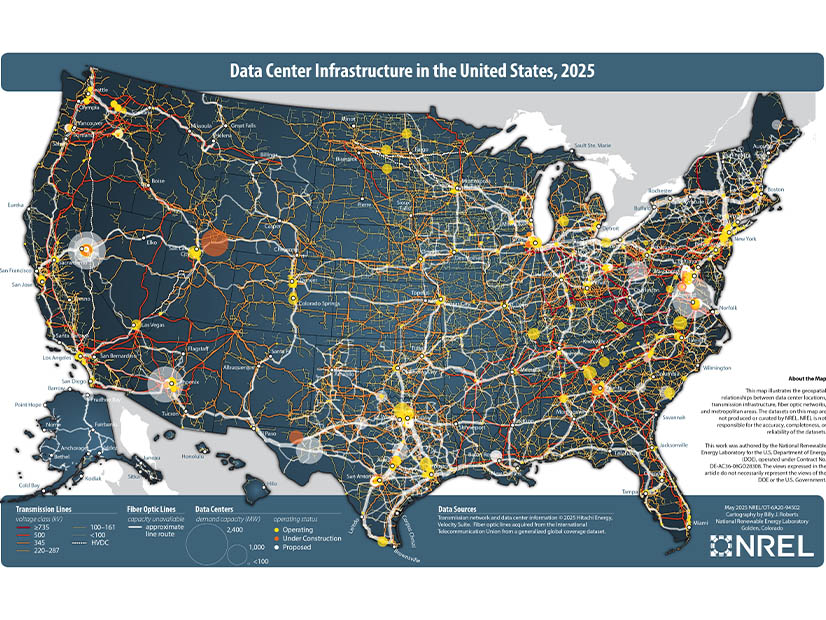

On July 7, the U.S. Department of Energy released a resource adequacy report noting that various organizations’ estimates of U.S. data center load growth by 2030 range from 35 to 108 GW.

DOE adopted a midpoint assumption of 50 GW — plus 51 GW of non-data center load growth — to conclude the nation will be unable to meet projected demand “absent decisive intervention” because 104 GW of baseload retirement and only 22 GW of new baseload generation is planned by 2030. (See DOE Reliability Report Argues Changes Required to Avoid Outages Past 2030.)

The DOE report called for rapid and robust reforms, lest adversary nations shape the digital norms and control digital infrastructure.

But others say these are the latest overestimations of a trend and that Big Tech will not need all this electricity.

“Uncertainty and Upward Bias are Inherent in Data Center Electricity Demand Projections” was written by London Economics International (LEI) and commissioned by the Southern Environmental Law Center (SELC). It also was released July 7.

LEI totaled the projections of data center load growth from RTOs, ISOs and balancing areas covering 77% of U.S. electric load; surveyed global projections for semiconductor chip production and supply; and factored in potential increases in chip energy efficiency and computing capacity.

They concluded that under the implied projection of 57 GW of data center load growth, the U.S. would need to buy 90% of all chips produced worldwide from 2025 through 2030, and said that scenario is unlikely — the U.S. now buys less than 50% of the global chip supply, and other nations are ratcheting up their own data center development.

LEI said these calculations support the anecdotal evidence that data center developers are submitting duplicate requests for grid interconnection in multiple jurisdictions that are being misinterpreted as unique requests.

However, the totals are being treated as real by some policymakers.

President Trump is easing and speeding the regulatory process in response to the national energy emergency he declared on the first day of his second term, in part to “power the next generation of technology” and “remain at the forefront technological innovation.”

This speedup raises environmental and safety questions for some observers, as well as financial worries: If more pipelines, wires and generators are built than data centers need, someone else will have to pay for the resulting overcapacity.

This is a central concern cited by SELC, which is headquartered in Virginia, home to the world’s largest concentration of data centers.

“This report underscores a critical and ongoing concern: Inflated and speculative data center electricity demand forecasts in the Southeast are driving a dramatic and unnecessary overbuild of infrastructure that threatens to lock in fossil fuels, hike energy bills and crowd out more reliable, cost-effective clean energy,” said Megan Gibson, senior attorney at SELC. “Such speculative infrastructure investment creates significant economic risks for ratepayers, who ultimately bear the financial burdens.”

Beyond the fundamental constraint of there not being enough semiconductor chips to supply the highest projections of data center growth, SELC noted, there are limits of powering a fleet of new data centers: There are equipment shortages for new large-scale natural gas-fired plants, nuclear reactors are expensive and slow to build, new-build coal appears unlikely, and wind and solar generation suffered major setbacks in the reconciliation bill Trump signed July 4. (See U.S. Clean Energy Sector Faces Cuts and Limitations.)

Shelley Robbins, the Southern Alliance for Clean Energy’s senior decarbonization manager, said there is immense financial incentive for suppliers and developers to game the system and overestimate demand.

“Data center growth has become a suspiciously convenient justification for pipeline and gas plant projects in the Southeast. Pipeline and utility companies make most of their money by building big things and then charging ratepayers for them,” Robbins said. “The result will be an expensive overbuild if we do not carefully scrutinize the genuine likelihood that data center loads will actually materialize.”