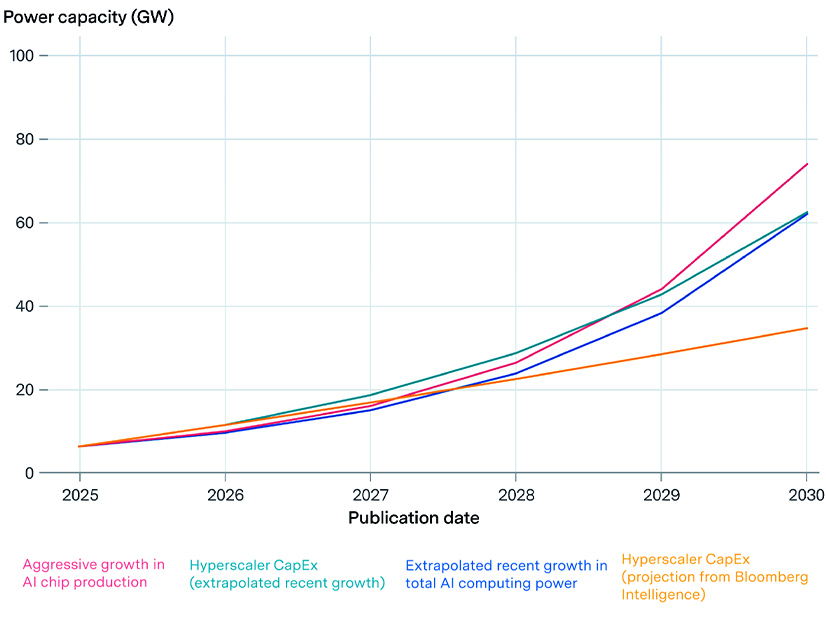

A new report by EPRI and Epoch AI estimates U.S. power demand by artificial intelligence could jump from 5 GW today to more than 50 GW by 2030.

The sharp rise is due not only to the growth in the amount of large-scale training but also its increasing duration, and is tempered only partly by hardware efficiency improvements, the two organizations said in their Aug. 11 announcement of “Scaling Intelligence: The Exponential Growth of AI’s Power Needs.”

Beyond large-scale training, more power capacity will be needed for AI research and for the actual use of finished AI models. But the training needs alone are formidable: Power consumption for training cutting-edge AI models is doubling annually.

“Frontier AI training runs — the computationally intensive process of training large, advanced AI models — currently consume approximately 100-150 MW each and are projected to reach 1-2 GW each by 2028, exceeding 4 GW per training run by 2030,” the authors write.

Training duration is assumed to have a 10% to 20% annual growth rate in the future. This compares with 25% to 50% in recent years. Increasing the duration can spread the same amount of power use across over a longer period, smoothing out peak demand. But the authors say durations now exceed 100 days, so further increases may yield diminishing returns.

Meanwhile, for the study, hardware efficiency is assumed to improve 33% to 52% annually.

The authors say the split of demand between training AI models and using them is important, as it could affect the size, location, power demands and potential flexibility of AI data centers. But it is currently uncertain, and the landscape is changing rapidly.

Some forecasts show AI consuming more than 5% of U.S. generation capacity by 2030, with some training runs equivalent to the output of entire power plants.

As has been noted many times, meeting such a level of peak demand just with new capacity could be quite challenging and extremely expensive. Some flexibility of demand during peak periods would help make the process less expensive and difficult.

The authors suggest: “Planning should account for both concentrated and distributed data center loads as well as the potential for real-time flexibility in training and inference workloads and from on-site generation and storage assets.”

“Inference” — usage of a trained AI model, such as generating responses to user requests — could support more flexibility than AI training.

The authors state that the rapid rate of growth of AI computing seen recently and projected in the next several years almost certainly must slow by the 2030s, because it is accompanied by a growth in cost that is not quite as rapid but is nevertheless unsustainable.

Whether that slowdown starts before 2030 may depend on technical innovations, data constraints or diminishing returns to scaling, they write.