The full 11-member D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals spent three and a half hours Monday grilling attorneys in a case that could decide whether FERC is allowed to give itself deadline extensions for when it must decide whether to rehear its decisions.

If the court overturns its precedent of allowing FERC’s use of so-called “tolling” orders — in which the commission grants a request for rehearing for the “limited purpose of further consideration” so that it is not automatically rejected — it could create a glut of litigation.

On the other hand, it might not have any real practical effect, as some judges seemed to indicate in their questioning.

Atlantic Sunrise

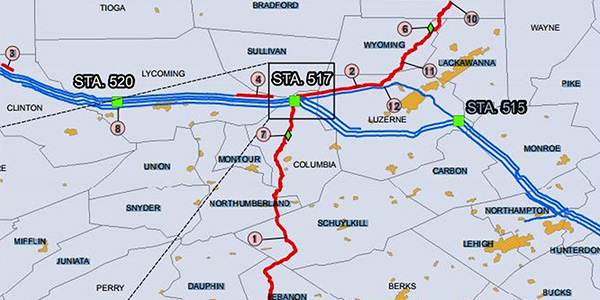

The case stems from FERC’s 2017 approval of — and subsequent rehearing request rejection for — Williams Companies’ Atlantic Sunrise project, an expansion of the company’s existing Transcontinental Pipeline. The project’s main component was a new 177-mile segment running from Susquehanna County in northern Pennsylvania to Lancaster County, near the state’s border with Maryland. Williams began construction on the pipeline in September 2017 — three months before FERC rejected rehearing requests from landowners and environmental groups — and it entered service in October 2018 (Allegheny Defense Project, et al. v. FERC, 17-1098).

Pennsylvania portion of Williams’ Atlantic Sunrise natural gas pipeline project, which began service in late 2018 after winning FERC approval in February 2017. | Williams

Under Section 19a of the Natural Gas Act (15 U.S.C. § 717r(a)), “unless the commission acts upon [an] application for rehearing within 30 days after it is filed, such application may be deemed to have been denied. No proceeding to review any order of the commission shall be brought by any person unless such person shall have made application to the commission for a rehearing thereon.”

Since 1969’s California Company v. Federal Power Commission, the D.C. Circuit has judged that issuing a tolling order within the 30-day time frame meant that FERC had “acted upon” the request under the language of the statute, and that parties must wait until the commission’s review of the request is actually complete before seeking relief from the court. Citing this precedent, a three-judge panel of the court in August 2019 rejected the plaintiffs’ petition.

But in December, the full court agreed to rehear the case en banc. The plaintiffs had also argued that FERC had failed to consider the pipeline’s downstream greenhouse gas emissions in an environmental impact statement or that its reliance on precedent agreements to indicate need was incorrect. But the court specified that it was only interested in the plaintiffs’ argument that FERC’s use of tolling orders had improperly delayed their ability to seek relief from the court, depriving them of due process. (See DC Circuit to Reconsider FERC Tolling Orders.)

The court’s original March 31 date for oral arguments was delayed because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Instead of meeting at the E. Barrett Prettyman U.S. Courthouse, the court heard arguments by teleconference Monday, which was streamed live on YouTube.

An Issue of ‘Finality’

Some of the judges at first seemed confused by what the plaintiffs were seeking. They asked attorney Siobhan Cole, of White and Williams LLP, whether she was arguing that the NGA’s language meant FERC had to rule on the merits of the rehearing request within the 30-day deadline.

Not necessarily, Cole said. “The request for rehearing could be granted and then something else could follow to decide the merits of whether the underlying certificate order should actually be altered,” she said. “But the key distinction there is that the finality of the underlying certificate order has to be stripped away as soon as rehearing is granted.”

Some judges were skeptical that the rehearing process would be different even if they eliminated tolling orders. They wondered whether FERC could grant rehearing within 30 days but still take an indefinite amount of time working on the rehearing order itself.

Judge Merrick Garland said he was “happy to accept the idea that a tolling order, which is only granted for purposes of giving more time, is not envisioned by the statute,” but he seemed skeptical of the idea that granting rehearing automatically “abrogates the underlying certificate.”

Cole acknowledged that there was no such provision in the NGA, and even granted that, absent an order from the commission or the court to stay the project, the certificate would remain in force while the judicial process played out. But she said granting what Garland eventually termed an “honest” rehearing would allow parties to seek a stay in court while the commission worked on the merits of the request.

“If the commission is going to rehear its order, it cannot at the same time say that it is confident in the accuracy of the order such that construction and takings [of property using eminent domain] can move forward,” Cole said.

Judge Judith Rogers expressed a similar sentiment as Garland. “I understand how you come out ahead for your client in the formulation that any grant of a petition by the commission destroys the finality of the underlying certificate.” But she did not understand what her clients would gain absent that specific finding.

“It still gives them at least the opportunity for judicial review, and it leaves open the possibility that if the commission were acting under an error of judgment or otherwise incorrect … the court could find fault with FERC’s determination, or simply decide the question of irreparable harm,” Cole responded.

ClearView Energy Partners said the arguments mean “that the D.C. Circuit might be prepared to consent to judicial review of the underlying order if FERC’s ‘action on rehearing’ was only a tolling order. Then, to the extent the commission wanted more time, it could request it of the court, not indefinitely stop the clock until it chooses to act.”