A new study finds that analyses by PJM’s Independent Market Monitor predicting increased costs for regions that exit PJM’s capacity market are skewed by their assumptions and should be redone to presume exiting states will maximize imports to counter local market power.

“The reports’ cost estimates risk confusing or even misleading states to the extent they suggest confidence that FRR [fixed resource requirement capacity procurements] will yield higher prices than continued reliance on PJM’s RPM [Reliability Pricing Model],” said the report by Rob Gramlich, president of Grid Strategies, and consultant Miles Farmer, a former attorney for the Natural Resources Defense Council.

“At this stage, given uncertain market dynamics and questions surrounding how states and utilities may implement FRR, it is difficult for anyone to render a confident and accurate prediction of FRR prices. While Monitoring Analytics provides useful data and a structure to evaluate FRR costs, we recommend that it provide a more complete picture of the potential costs of FRR by conducting additional scenarios applying the reasonable assumption that FRR entities would competitively procure externally-located capacity.”

Gramlich and Farmer released their study Wednesday, the New Jersey Board of Public Utilities’ deadline for comments in its docket on the state’s options for ensuring resource adequacy. (See related story, NJ Regulators Weighing Input on Capacity Market Exit.) The report expanded on the critique Gramlich has made in recent forums with Joe Bowring, president of Monitoring Analytics. (See PJM Monitor Defends FRR Analyses in MOPR Debate and Moving Forward on MOPR.)

The Monitor said its analyses in Illinois, Maryland and New Jersey indicate ratepayers are likely to see costs increase if their jurisdictions leave the PJM capacity market for an FRR. The reports also concluded that the expanded minimum offer price rule (MOPR) is unlikely to increase capacity costs, at least for the first couple of auctions. (See PJM Monitor Finds Capacity Exit Costly for NJ.)

The Gramlich-Farmer report did not attempt to quantify the impact of an FRR, but it said “a reasonable set of assumptions yields lower price estimates for FRR than for continued reliance on RPM.”

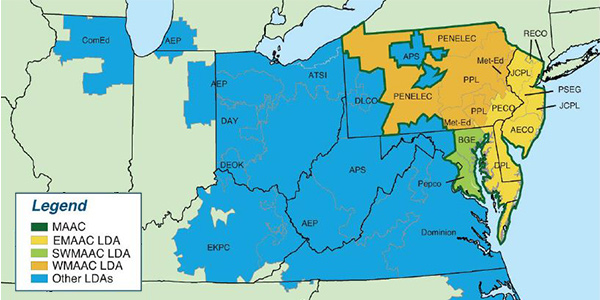

The authors said any analysis should assume that an FRR service area located partially or fully within a constrained locational deliverability area (LDA) would seek to purchase as much capacity as possible at lower prices outside the LDA before “meeting the rest of internal load with internal generation.”

They said states should request that the Monitor provide them data on the maximum import capability into constrained zones, which will determine the minimum internal resource requirements.

“Monitoring Analytics reports all suffer from a central flaw: they assume that FRR entities would purchase as much capacity as possible from internal resources, importing capacity only to the extent ‘needed to cover any shortfall in meeting the FRR obligation,’ even where the FRR entity is located within a transmission-constrained area where local capacity prices are higher than those of the importing region(s),” the report said. “Monitoring Analytics never justifies this assumption, which leads to higher prices across all scenarios that modeled an FRR entity located entirely or partially within a transmission-constrained LDA.

“While this framing suggests an apples-to-apples cost comparison, in fact it yields skewed results that in effect presume an irrational capacity purchasing strategy by the FRR entity.”

Bowring continued to stand behind his analyses Thursday, saying, “It is extremely unlikely that the FRR approach will result in prices equal to or lower than market prices.”

He criticized the Gramlich-Farmer report’s references to the resource adequacy policies of MISO and CAISO, saying neither are markets. “MISO relies on cost-of-service regulation with its attendant high costs and lack of competition, and CAISO relies on an inefficient process of bilateral contracting for capacity.”

The report noted that the Monitor found a 5.4% reduction for an FRR in Maryland’s PEPCO LDA — which is not constrained by a binding transmission import limit — under a scenario in which capacity prices would be equal to the most recent Base Residual Auction.

Gramlich and Farmer also questioned why half of the Monitor’s scenarios assumes all suppliers — not just pivotal suppliers that possess market power — will be paid prices at the seller offer cap.

“Market power is a significant challenge that states, PJM and FERC should carefully address in designing and implementing FRR. But it is important to recognize that FRR does not ‘create’ market power, which flows from the underlying dynamics of market suppliers’ generation ownership and relevant transmission system constraints,” they said.

They also disagreed with the Monitor’s conclusion that the expanded MOPR will not increase costs in upcoming BRAs. Gramlich this week released a study projecting that the expanded MOPR will cost ratepayers $9.7 billion or more over the next nine years. (See New MOPR Analysis Sees Cost at $1B/Year.)

“MOPR will raise RPM costs to the extent it raises market clearing prices by causing higher priced supply offers and to the extent it forces customers to support the construction or retention of redundant capacity. MOPR also could increase the cost of state programs because state-supported resources that do not clear the capacity market may require more revenue from renewable energy credits (RECs) and other payments in order to cover their costs and be developed as the states desire.”

In contrast, Gramlich and Farmer said, FRR programs could procure capacity from state-supported resources at prices that reflect state subsidies. “The costs of state clean energy policies would also be reduced as compared to BRA with MOPR because state-supported resources could more confidently rely on capacity revenues.”

The authors said lower costs are likely under FRR because it would require only a 15% reserve margin — using a vertical demand curve and fixed MW requirement — rather than the 22% margin in recent RPM auctions, which uses a sloped demand curve. They cited an estimate from ICF that the lower reserve margin under FRR could reduce prices by $15 to $25/MW-day in the near term and $30 to $50/MW-day in the long term.

The study also said FRR would give utilities and states more flexibility because non-performance penalties could be assessed on a physical and portfolio-wide basis rather than as an economic penalty applied to individual units under RPM. They said unit-specific financial penalties have been a disincentive to renewables’ participation in the capacity market.

Bowring questioned why Gramlich and Farmer assert “that the weaker performance incentives in an FRR would be a good thing. “An essential point of the Capacity Performance design was to strengthen performance incentives. One of the strengths of well-designed markets is that investors bear the risks associated with the performance of their assets,” he said.

FRRs could make better use of seasonal resources than RPM, they said, citing a Brattle Group report that concluded separating summer and winter capacity markets in PJM would save consumers $100 million to $600 million annually.

FRRs also could obtain lower prices by giving sellers multi-year price locks. “Price formulas could partially or fully index to RPM. And the purchase could also be combined with energy, ancillary services or environmental attributes providing the purchaser and seller more certainty as to their total costs and revenues.”

The authors acknowledged that PJM rules bar utilities from returning to the capacity auction for at least five years after departing (though PJM allows an exception if state regulatory changes materially affect consumers’ retail choice options).

They also noted concerns that state regulators would have to prevent distribution companies from acting on incentives to favor their own generation under an FRR.

Under PJM rules, the entity responsible for obtaining capacity could be a utility, distribution company or state agency. Legislation pending in Illinois would give such responsibility to the Illinois Power Agency. (See Clock Ticking on Exelon Illinois Nukes Under MOPR.)