The New England Power Pool Markets Committee devoted the bulk of its two-day summer meeting to debating changes to inputs and assumptions that will govern Forward Capacity Auction 16 in February 2022 for the 2025/26 capacity commitment period.

ISO-NE is proposing to update the cost of new entry and net CONE calculations, and to recalculate the offer review trigger prices (ORTPs).

Principal market development analyst Deborah Cooke gave a presentation outlining two proposed adjustments to the energy and ancillary services (E&AS) revenue offsets used to calculate net CONE and ORTPs.

One adjustment would account for estimated revenues under the Energy Security Improvements (ESI) market design. The second — a “level of excess” adjustment — seeks to account for surplus generation above the net installed capacity requirement (ICR) based on the one-day-in-10-years loss-of-load expectation.

Cooke noted that the system has been long on capacity since the 2016/17 capacity commitment period, with a 2,006-MW excess for 2019/20.

E&AS revenue offsets will be calculated reflecting both current and future market conditions, including revenue impacts from ESI, both as proposed by ISO-NE and as proposed by NEPOOL, and the elimination of the Forward Reserve Market. (See “FRM Sunset by 2025,” NEPOOL Markets Committee Briefs: June 10, 2020.)

Detailed E&AS Revenue Offsets

Engaged by the RTO to support the updates, Concentric Energy Advisors’ Danielle Powers and her colleagues also presented a review of detailed capital and operating costs for CONE (simple cycle and combined cycle) and ORTP (solar, battery storage and onshore and offshore wind) units.

Their methodology used a simplified hourly dispatch model of the units’ E&AS awards in the day-ahead and real-time markets to estimate E&AS revenues. Unit dispatch was based on adjusted historical day-ahead and real-time LMPs.

Additional revenue adjustments made outside of the dispatch model included energy/reserve scarcity hour revenues and expected Pay-for-Performance (PfP) payments.

The expected impact of energy and reserve shortage hours in the future are incorporated in a standalone energy/reserve scarcity hour adjustment outside of the E&AS dispatch model.

The issue is complicated by having a great number of moving parts, but the analysis will be a little easier to understand at the August MC meeting after they pull more of it together, Powers said.

Concentric will continue to refine its analysis and, at the August meeting, will have incorporated ESI assumptions and analysis into the CONE and ORTP models. It will also review financial assumptions and its preliminary findings on demand response and energy efficiency.

The RTO proposes to file any calculation changes with FERC by Dec. 1.

FCM Parameter Updates for 2025/26 Period

ISO-NE Lead Analyst Kevin Coopey presented estimates of expected capacity scarcity condition (CSC) hours and related factors for updating the parameters for the 2025/26 capacity commitment period.

The summer peak-load CSCs account for 14.1 hours of the 15.3 hours expected annually for 2025/26.

Transient CSCs (estimated at 0.8 hours annually) arise from operational risks such as system under-commitment, load forecast error and the loss of critical transmission elements, Coopey said. Unlike peak-load scarcity, transient CSCs tend to be shorter in duration and usually occur at lower load levels. Winter CSCs (estimated at 0.4 hours per year) can arise from several causes, notably natural gas supply constraints during cold weather.

Coopey said the peak load analysis is based on the two peak-load CSCs that have occurred since December 2014: Aug. 11, 2016, and Sept. 3, 2018.

Several stakeholders questioned the rationale for classifying a CSC event as peak-load or transient, and whether using two events provides sufficient data to draw statistical conclusions about average balancing ratios, which reflect the lower loads expected during transient and winter operating conditions.

“We’ve heard the feedback about trying to get GE MARS [General Electric’s Multi-Area Reliability Simulation Software] to generate a balancing ratio estimate,” Coopey said. “We’ll take that back to the ISO.”

[Note: Although NEPOOL rules prohibit quoting speakers at meetings, those quoted in this article approved their remarks afterward to clarify their presentations.]

OSW Capital Costs Assumptions

RENEW Northeast and Daymark Energy Advisors made a presentation on offshore wind capital costs and renewable energy credit price assumptions for ORTP calculations.

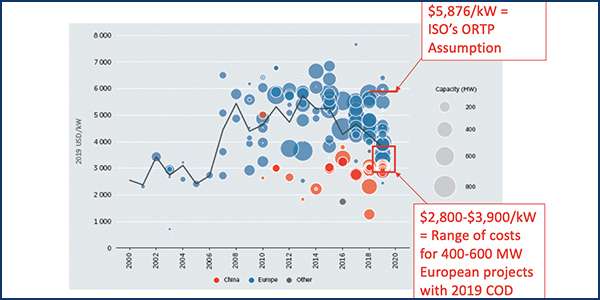

Alex Worsley of Boreas Renewables noted that ISO-NE proposed an overnight capital cost of $5,876/kW (2019$) for the FCA 16 offshore wind ORTP calculation.

“Looking at recent power purchase agreements pricing, as well as the latest publicly available data, and considering that current New England offshore wind developers with upcoming projects have significant experience building the largest wind farms globally, we believe that this cost assumption is unreasonable for projects to be built in 2024-2025,” Worsley said.

The RENEW analysis used a financial model of the offshore wind projects based on their executed PPAs. “We’ve also assumed that the developers are predicting some capacity revenues in addition to energy and REC revenues to determine their PPA price … but they wouldn’t have certainty over that [capacity] revenue, so this resulted in a conservative estimate for capital costs,” said Carrie Gilbert of Daymark.

Worsley said their PPA analysis shows implied capital expenditures ranging from $2,200 to $3,600/kW for projects currently under development, while the International Renewable Energy Agency’s shows a $2,800 to $3,900/kW range of costs for the larger European projects with commercial operation dates in 2019. Lazard’s 2019 levelized cost of entry analysis shows a $2,350 to $3,550/kW CapEx range.

“We suggest the overnight capital costs of this hypothetical 800-MW project to be built in 2024-2025 should be approximately $2,681/kW, and assert that the $3,195/kW difference between our capital cost assumption and the ISO’s cost assumption would significantly impact the ORTP value.”

As for ISO-NE’s REC assumptions, “previous treatment of RECs in ORTP calculation has been forward-looking, but the currently proposed REC assumption is purely historical and uses three lowest-price years in the recent past. So, this is a big departure from previous approaches and underestimates REC revenues,” Gilbert said.

Resource Balance for Net CONE

Robert Stoddard, managing director of Berkeley Research Group, introduced on behalf of the New England Power Generators Association (NEPGA) a presentation on resource balance for net CONE calculation.

The presentation questioned Concentric’s key assumption that the E&AS offset (and all other inputs to net CONE) should be calculated “at criterion.”

Stoddard said Concentric supports that contention by citing a non-decisional paragraph in a 2017 FERC order in which the commission said “net CONE is intended to approximate the compensation a new entrant would need from the capacity market in the first year of operation to recover its capital and fixed costs under long-term equilibrium conditions” (ER17-795).

Using the “at criterion” capacity balance has many negative consequences, NEPGA argues, such as requiring arbitrary and improbable adjustments to forecasts; ignoring impacts of energy-only resources; and overstating the expected number of scarcity hours.

In addition, competitive offers could be subject to undue mitigation, the ORTP may be set too low, and the FCM will be unlikely to produce sufficient revenue on average, Stoddard said.

CONE measures the cost of adding an incremental resource, and customers pay the difference between CONE and net CONE in E&AS markets, so CONE is the best measure of the expected total cost to consumers, the presentation said. Short of a full demand curve reset, the same expected price level can be achieved by using an “as expected” E&AS offset.

Exempting EE from PfP

Mark Spencer of LS Power presented a proposal to exempt energy efficiency resources from PfP, asserting that potential performance payments represent a miniscule revenue opportunity for EE resources.

The PfP program was implemented in June 2018 in order to ensure fuel security under severe winter conditions. Under the program, all resources with capacity supply obligations (CSOs) are assessed a charge — based on their gross FCA payments — when a “measurable” real-time operating reserve (RTOR) deficiency triggers a CSC.

The RTO redistributes the money collected from that charge as payments to CSO resources based on their performance during the RTOR event.

The bulk of EE funding is derived from surcharges to retail customers and a modest amount from Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative revenues, Spencer said.

Capacity revenue represents only 7 to 29% of the total funding streams, and long‐run expectations of PfP payment contributions to total funding are likely less than 1%, he said.

“What our recommendations are is to retain EE’s base capacity payments and to remove them from the PfP settlement, including the insurance pool, so they wouldn’t be subject to any of the deficiency or capacity payment performance charges that that obligation would entail, and to eliminate the requirement for them to provide credit support for the [Forward Capacity Market] delivery financial assurance,” Spencer said.

Backers of the proposal will continue to develop it before seeking a vote on the Market Rule 1 and Financial Assurance Policy changes at the September PC meeting.