Mid-century economy-wide GHG emission reduction targets in New England | E3/EFI

NEPOOL’s Participants Committee on Thursday began taking a new look at how it can adapt market rules to reach New England states’ decarbonization goals with educational presentations on two potential “pathways”: carbon pricing and a forward clean energy market (FCEM).

The pathways discussion — and planning for a parallel “Future Grid” study — resulted from requests by the New England Power Generators Association (NEPGA), New England States Committee on Electricity (NESCOE) and other stakeholders for the region to plot a path toward reaching states’ 2050 decarbonization goals. (See NEPOOL Reviews ‘Future Grid’ Study Requests.)

At the March PC meeting, NESCOE Executive Director Heather Hunt said the organization’s request was intended “to initiate proactive and actionable discussion on the future grid and potential market changes to achieve states’ goals other than through the reactionary changes that have been directed by the FERC and driven the region’s efforts in past years,” according to NEPOOL meeting minutes.

IMAPP Redux?

Carbon pricing and the FCEM were among four long-term proposals considered in detail by stakeholders in the Integrating Markets and Public Policy (IMAPP) initiative in 2016. Carbon pricing foundered because of differing ambitions among the states, with New Hampshire balking at the more ambitious goals of Massachusetts and Connecticut. (See ISO-NE Two-Tier Auction Proposal Gets FERC Airing.)

ISO-NE ultimately adopted a two-tiered capacity construct, the Competitive Auctions with Sponsored Policy Resources (CASPR) to prevent consumers from paying twice for the same capacity through both the Forward Capacity Market (FCM) and subsidies for new, state-mandated supply resources.

CASPR is intended to allow state-sponsored resources to enter the FCM while maintaining competitive prices in the Forward Capacity Auction (FCA). In a substitution auction after the primary FCA, existing capacity resources may transfer their obligations to new resources that did not clear in that first stage because of the minimum offer price rule.

The CASPR substitution auction cleared 54 MW in 2019 and none in 2020. That led some observers to label CASPR a failure, with others calling for it to be redesigned. (See NEPOOL Markets Committee Briefs: May 12, 2020.)

ISO-NE CEO Gordon van Welie has urged patience, telling the PC in March that CASPR is the “next best solution” if the region can’t adopt effective carbon pricing.

“Resource substitution via CASPR will depend on the build-up of economic pressures over time,” he said. He acknowledged CASPR’s performance thus far “has caused concern among some stakeholders that the transition may not occur swiftly enough, or that the lack of substitution may lead to a costly overbuild, leading to a discussion about alternative market designs or structures.”

Forward Clean Energy Market

At Thursday’s PC meeting, Kathleen Spees of The Brattle Group briefed members on its FCEM proposal, which she said could help states achieve their goals without demanding that those goals be uniform. “We developed the Forward Clean Energy Market as one tool that states could use for mobilizing private investment to meet their goals through a competitive market,” Brattle said.

The Brattle proposal resulted from a study funded by the Conservation Law Foundation, Brookfield Renewable Partners, NextEra Energy Resources and National Grid, and one funded by NRG Energy, Spees said.

The proposal acknowledges states’ desire to move from a wholesale market that delivers “reliable, low-cost electricity” to one in which the power is also carbon-free, Spees said.

[Note: Although NEPOOL rules prohibit quoting speakers at meetings, those quoted in this article approved their remarks afterward to clarify their presentations.]

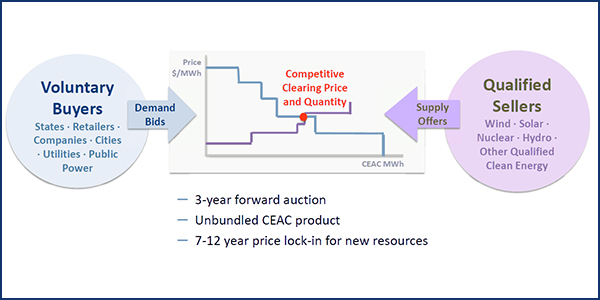

The FCEM would be a centralized, three-year forward auction in which buyers and sellers could voluntarily exchange clean energy attribute credits (CEACs) — a product Spees likened to a renewable energy credit.

Brattle’s proposed Forward Clean Energy Market would be a centralized auction in which buyers and sellers could voluntarily exchange clean energy attribute credits (CEACs). | The Brattle Group

There are two optional variations: One for a “dynamic” CEAC would award more credits to resources that displace more carbon emissions, which would benefit batteries “and focus incentives toward achieving more carbon abatement faster,” Brattle said.

A second option would allow buyers to register a preference for “targeted” resource types to meet carve-outs for preferred technologies such as storage or offshore wind.

The FCEM would assign most fundamentals-based and asset-specific risks to sellers, with features to mitigate regulatory risks and support financeability:

- a multiyear commitment period of about seven to 12 years to lock in prices for new resources;

- a multiyear forward period to support development and financing of new resources;

- a sloped demand curve to reduce year-to-year price volatility and improve revenue certainty; and

- the ability for states to make commitments to rely on the market for a minimum time frame and quantity to ensure confidence in the construct.

Spees indicated a willingness to discuss a forward period shorter than three years, which could benefit some renewable developers. But she noted that some clean resources such as offshore wind may also have longer development time frames. She recommended that the FCM and FCEM both be conducted at the same forward period to minimize clearing risks for new resources that seek financing.

Brattle said its simulations estimated that FCEM could save customers $3.60/MWh — or $4.5 billion over 10 years — compared to states’ current practices for bringing clean resources and storage online, including competitive solicitations.

Spees said the FCEM offers several benefits over carbon pricing and traditional RECs.

Carbon pricing maximizes benefits if implemented regionally and economy-wide, which may not be politically feasible in the near term; carbon prices acceptable to all states would likely be too low to achieve the carbon-reduction goals. The FCEM, by contrast, would not require states, cities or companies to agree on a common price or policy goal: States and customers pay to meet their own goals with no cost-shifting to nonparticipants.

Brattle says traditional RECs offer flat incentives over every hour and incentives to offer at negative energy prices during excess energy hours when displacing other clean supply.

“Dynamic” CEACs would scale payments in proportion to marginal CO2 displacement by time and location, incenting the production of clean energy when and where it is most effective in reducing emissions, Spees said. There would be no incentive to offer at negative prices.

Spees said she was uncertain whether the plan would be subject to FERC jurisdiction or outside it like the REC market and the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative. Either way, she said, “it’s critical that states have control over their participation. States were very clear when we went through the IMAPP that they want that flexibility.”

Carbon Pricing

Joe Cavicchi of Analysis Group also gave a presentation on the NEPGA-funded carbon pricing study it released in June.

Joe Cavicchi, Analysis Group | Analysis Group

Cavicchi began his presentation with a look at Western Europe, where carbon spot prices, which he said had been ineffectual at about 5 euros/metric ton in 2017 ($5.89), have generally traded between 20 and 25 euros since 2018 ($23.57 to $29.47).

Analysis Group’s study concluded that New England needs a CO2 price of $25 to $35/short ton by 2025, rising to $55 to $70 by 2030, to meet states’ carbon emissions goals. (See Study: $25 Carbon Price Needed to Meet Goals.)

The Analysis Group’s study concluded that New England needs a carbon price of $25 to $35/short ton by 2025, rising to $55 to $70 by 2030, to meet New England states’ carbon emissions goals. | Analysis Group

Cavicchi said a multisector price on carbon could help the transformation to electrification, allowing “a more accurate assessment of the trade-offs when assessing electricity as a fuel for transportation and heating as opposed to fossil fuels.”

It also would allow technology-neutral competition among existing and new zero-emission resources in the electric sector, incentivizing cost reductions and innovation while reducing the need for future state-directed investments. It would additionally reduce the risk of stranded investments that can result when the costs of power from new technologies drop below long-term contract prices.

The study assumed light-duty electric vehicle penetration of 25% in 2025, 60% in 2030 and 90% in 2035. Similarly, it assumed 25% of homes heating with oil, propane or natural gas would switch to electric by 2025, rising to 50% by 2030 and 75% in 2035.

Although a carbon price would increase wholesale power prices, it would not increase consumer costs materially if states rebate the carbon revenues, the study said.

Next Steps

The PC next month will receive education on energy-only markets, such as ERCOT, and alternative approaches to the region’s existing reliance on the FCM for resource adequacy.

The committee expects to begin discussing the pros and cons of the potential solutions in October.

Consent Agenda

Earlier in the meeting, the PC approved the following on the consent agenda:

- The amended and restated Services Agreement between NEPOOL and ISO-NE reflecting the evolution in the roles of ISO-NE, NEPOOL and the NEPOOL Generation Information System Administrator, as recommended by the Markets Committee at its July 14-15 meeting.

- Revisions to metering requirements for DC-coupled assets: Manual M-28 (Market Rule 1 Accounting) and Manual M-RPA (Registration and Performance Auditing), as recommended by the MC in July.

- Revisions to OP-18 (Metering and Telemetering Criteria), which adds requirements for DC-coupled assets, as recommended by the Reliability Committee at its June 16 meeting.

- Revisions to Planning Procedure No. 5-1 (Procedure for Review of Market Participant’s or Transmission Owner’s Proposed Plans) in response to the significant increase of proposed plan applications and generator notification forms being processed monthly. Submittals will be required 10 business days before the monthly RC meeting date. Generator application forms have been updated to enable bulk review and summarization, and information regarding the storage component of co-located facilities will be collected to enable improved summarization. The change was recommended by the RC in June.