Offshore wind advocates are calling for changes to RTO transmission planning and cost allocation rules to reduce costs and development risks for connecting an estimated 30 GW of generation on the East Coast through 2035.

In a white paper released Oct. 26, the Business Network for Offshore Wind lays out its view of the policy options facing FERC, RTOs and states and the changes it says could ensure the most cost-effective transmission buildout. Grid Strategies’ Michael Goggin, who contributed to the paper, will be among 25 witnesses scheduled to appear Tuesday at a FERC technical conference on offshore transmission.

Brandon Burke, policy and outreach director for the Business Network and the primary author of the paper, said current RTO processes fail to capture all the benefits of offshore transmission, particularly that of an interregional network that could improve resilience in PJM, NYISO and ISO-NE.

It also says OSW development could be hamstrung by the “free rider” problem: that transmission upgrades paid for by an individual generator can benefit those who did not contribute.

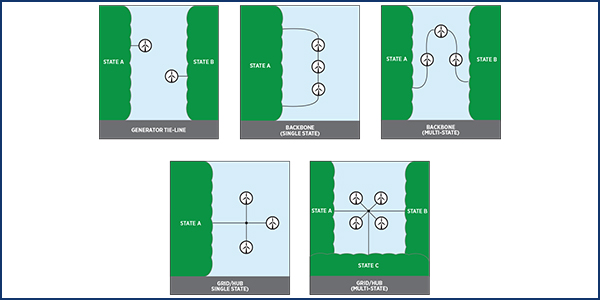

Potential offshore wind transmission topologies | Business Network for Offshore Wind

OSW Targets, Projections

Connecticut, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York and Virginia have set targets to procure 29.1 GW of OSW by 2035, with almost 6.3 GW of procurements awarded, according to the American Wind Energy Association. The departments of Energy and the Interior say the U.S. could deploy up to 86 GW of OSW, including on the West Coast and in the Great Lakes by 2050. “Aggressive decarbonization” could result in more than 100 GW on the East Coast alone, according to the white paper.

Although OSW resources on the East Coast are relatively close to load centers, they are generally distant from optimal points of interconnection to onshore transmission networks. “In many areas, only lower-voltage transmission and distribution lines extend to the coast, though at certain points high-capacity transmission lines do extend to existing or retired coastal power plants,” the Business Network said. “When the capacity of the existing onshore electricity grid is reached, and low-cost points of interconnection have been utilized, these grid/interconnection constraints could arrest the future growth of the U.S. OSW project pipeline.”

The report identifies eight models for offshore transmission and its cost allocation, including private generator lead lines — the approach being used for the first group of U.S. OSW projects — and one employing partial federal funding.

Planned vs. Project-by-project Approach

“The optimal outcome will almost certainly involve a mix of both generator tie-line and network elements,” the group said. “While there is debate about the optimal configuration of offshore transmission and the onshore grid upgrades necessary to integrate it, a planned transmission strategy is almost always ultimately more efficient than an unplanned, project-by-project approach.”

An offshore transmission network that connects multiple OSW projects would optimize onshore upgrades and make more efficient use of the limited number of optimal onshore interconnection points. It also could benefit from economies of scale by using higher-capacity transmission lines and converter stations, the Business Network says.

Networked offshore transmission also would allow for rerouting power during interruptions on a single tie line and increase the utilization factor of individual network lines “because geographic diversity causes wind plants to have different output patterns, allowing sharing of network capacity.”

Brattle Group analyses of New England and New York have found that a planned approach could minimize environmental disruptions by reducing the total length of installed cable by about half versus a project-by-project approach.

Costs, Curtailments

The paper says putting 30 GW of OSW in service would require about $100 billion in capital spending, up to $20 billion of it for offshore transmission; onshore upgrades would be “comparably large.”

It cited a Brattle study that a planned offshore network in New England would cost $500 million less in capital spending with savings of $55 million annually from reduced power losses. It could also produce another $300 million in yearly savings by delivering power to higher-priced locations on the grid.

After the first 6.7 GW of OSW is installed, Brattle said, using generator tie-lines to interconnect the remaining 8 GW of capacity in the New England OSW lease areas would result in 13% curtailment, compared with 4% under a planned approach.

East Coast wind lease areas and major onshore transmission | Business Network for Offshore Wind

Risks of Network Model

But the paper acknowledged “considerable debate regarding whether a planned offshore transmission network connecting multiple OSW facilities to shore versus an incremental approach driven by generator tie lines serving individual OSW installations will better facilitate the steady expansion and long-term success of the U.S. OSW industry.”

An offshore network entails more regulatory, political and other risks than generator tie lines for individual projects, which it said can undermine the ability to attract investors.

“As the scale of the proposed transmission solution increases, from an individual offshore wind facility tie line, to a line serving multiple OSW projects, to a network line with multiple onshore points of interconnection, and finally to an interregional offshore network, there are increases in both the potential benefits and the policy and political challenges that must be overcome. …

“The permitting process [for shared offshore transmission] is at best unclear,” the Business Network said, noting FERC’s ruling in July that PJM can deny injection rights to merchant offshore transmission networks unless the project also connects to another grid operator. (See FERC Rules Against Anbaric in OSW Tx Order.) Anbaric appealed the ruling to the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals on Oct. 16.

Role for Government

The paper said “the most fundamental problem” with RTOs’ transmission planning is the reliance on the generator interconnection queue process to determine what transmission should be built. “The lens of generator interconnection is just one of many benefits of those transmission upgrades.”

Because of the “free rider” phenomenon, the white paper says “there is an essential role for government policy in ensuring that adequate transmission is built to realize … societal benefits, similar to the role governments play for highways, sewer systems and rail networks.”

In many regions, the cost of large upgrades to the grid are assigned to interconnecting generators even though the upgrades benefit the entire region, the group said. “An analogy to that policy would be requiring the last vehicle entering a congested highway to pay the full cost of adding another lane to the highway.”

Potential landing spots for offshore wind generators | Business Network for Offshore Wind

The group said the risks of network models can be reduced by policy changes clarifying “how transmission will be planned, paid for and permitted.”

The white paper also sees a potential role for DOE in optimizing transmission development, noting that three RTOs and their 20 states and D.C. will have roles in determining transmission planning and cost allocation for OSW on the East Coast.

“Currently, there is no single entity responsible for planning offshore transmission across the East Coast, convening stakeholders and working with the industry and states on transmission options,” it said, suggesting DOE could provide technical research and support for stakeholder engagement. “Potential studies include analyzing the benefits of different scales and configurations of transmission expansion, quantifying how expanded transmission can reduce capacity and energy costs by capturing interregional diversity in electricity supply and demand, and finding solutions that minimize the total cost of onshore and offshore transmission.”

Beyond Order 1000

It called on FERC to build on Order 1000 by requiring RTOs to incorporate public policy requirements — such as states’ renewable portfolio standards and OSW procurements — into transmission planning. Order 1000 “only required regions to ‘consider’ public policy requirements. State OSW mandates and procurements need to be integrated into transmission planning, as they are law and the procured offshore projects are being built,” it said.

The group also says current interregional transmission planning processes have failed to identify large projects that would benefit multiple regions because “although Order 1000 requires neighboring transmission planning regions to coordinate planning, it does not require a joint process or evaluation of interregional solutions and their benefits.”

PJM’s response to Order 1000 — the “state agreement” approach — “provides an opening for eastern PJM states with OSW targets to partner [and] pay for transmission” but fails to address the free rider problem, the Business Network said. “If a state will benefit from another state’s transmission investment whether they pay for it or not, they have little incentive to pay for it. However, if each state refuses to pay for transmission upgrades that benefit the entire region, nothing gets built and the entire region suffers.”

It said the interconnection queue cluster process, in which a large number of interconnection applications are evaluated simultaneously and share upgrade costs, could achieve some economies of scale but also fails to allocate the costs to all those who will benefit from additional transmission capacity. “Moving transmission planning and cost allocation to the regional transmission planning process is the only solution for that problem,” it said.

The current interconnection process also leaves generation developers at risk that initial upgrade estimates will escalate if others in the transmission queue drop out.

Counting all Benefits

The Business Network also says RTOs are “leaving economic, reliability, resilience, hedging and other benefits on the table” because they are difficult to quantify. “In cases in which precise quantification is not possible, using an estimate will result in a more optimal level of transmission investment than arbitrarily assigning zero value to a benefit that is widely acknowledged to be large. If benefits are not quantified, they should be at least qualitatively taken into account in the planning process.”

It said transmission planners should use at least a 15-year time horizon for OSW transmission cost-benefit analyses and use advanced modeling to co-optimize transmission and generation planning.

RTO planners “have chosen short time horizons, often 10 years, to calculate the benefits of transmission because of future uncertainty around generation and load. With renewable resources, however, future generation additions will occur in the locations with optimal resources. Those locations are known today and are unlikely to significantly change over time,” the Business Network said. “Transmission assets typically have a useful life of 40 years or more, and that lifetime can often be indefinitely extended by replacing key pieces of equipment.”

Success Stories of Proactive Tx Development

As examples of the “proactive” approach to transmission planning that facilitates renewables, the Business Network cited Texas’ Competitive Renewable Energy Zones, California’s Tehachapi Wind Resource Area near Los Angeles and MISO’s Multi-Value Projects.

“MISO’s approach considers the value of transmission for meeting economics, reliability and public policy (renewable interconnection to meet state RPS requirements) needs. MISO made sure to spread planned transmission projects across the entire MISO footprint to ensure that all zones received projects and had a strong benefit-to-cost ratio, ensuring their support for the overall portfolio.”