New England stakeholders frustrated by states’ inability to meet their clean energy goals within ISO-NE’s markets considered last week whether a forward clean energy market (FCEM) might provide a solution.

“I think it’s fair to say that the idea of a forward clean energy market … is one that seems to have great salience for the challenges we face here in the region,” Peter Fuller, principal and founder of Autumn Lane Energy Consulting, said during a Northeast Energy and Commerce Association webinar Wednesday. “It’s one that people have felt ought to be given serious consideration by the states, NEPOOL, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission and all of the many stakeholders really interested in the success of that market.”

As NEPOOL Reconsiders Forward Clean Energy Market.)

Fuller said it is “becoming increasingly clear that the wholesale market can and should be changed” to address states’ carbon-reduction goals.

In recent years, partly because the wholesale market was not delivering clean energy to the degree that several New England states wanted, they have utilized long-term contracting and procurements of solar energy and offshore wind.

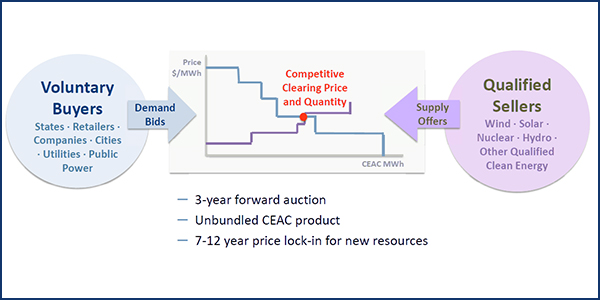

“It may be that a more robust competition between resources that can deliver carbon-free energy [is] both more reliable and more cost-effective for ratepayers; that’s at least the hope related to the forward clean energy market,” Fuller said.

Federal-State Conflicts

He said the FCEM design would address the conflict between state and federal policymakers on issues such as the minimum offer price rule (MOPR) and Competitive Auctions with Sponsored Policy Resources (CASPR), a two-tiered capacity construct intended to prevent consumers from paying twice for the same capacity through both the Forward Capacity Market (FCM) and subsidies for state-mandated resources.

“We think FCEM can be a vehicle to address that conflict,” Fuller said.

Michelle Gardner, senior director of regulatory affairs in the Northeast for NextEra Energy Resources, added that “looking at the massive transition that we’re anticipating over the coming decades, to me this is really about harnessing the competition and the balance between both new and existing resources.” She said states could do solicitations for existing resources, “but for the most part, the existing resources in the market that do contribute to carbon abatement are not valued.”

Rebecca Tepper, chief of the Massachusetts Attorney General’s Office Energy and Telecommunications Division, said that “markets are not going to bring us to or sustain a low-carbon future as they are currently designed.”

At a symposium the AG’s office held last year, two reasons were cited for why the markets were not working, Tepper said.

“One, it wasn’t bringing in the renewables, because of the MOPR, and that was resulting in double-counting,” Tepper said. “And two was resource adequacy. The forward clean energy market addresses No. 1, but it’s not designed to address No. 2.”

While the current system design is based on peak-hour demand, a transition to more clean energy will require availability at all hours of the day, Tepper said.

“We’re going to need to value other products like ramping and storage and others to incentivize them to address resource adequacy,” Tepper said.

Do the states have to control or have a more significant influence on an FCEM to work? Fuller said the market design “would be explicitly designed to create a high degree of control for the states.”

“I think who does the market administration is less important than making sure that it’s done in a way that passes muster in terms of nondiscriminatory competition among sources,” said Fuller, who added that the ultimate idea is to procure a generalized low-carbon product at the lowest possible cost.

Greg Cunningham, vice president and program director for clean energy and climate change at the Conservation Law Foundation, said existing programs such as state renewable portfolio standards could work with an FCEM.

“It’s conceivable that a form of RPS compliance could be participation in this market,” Cunningham said. “It obviously would have potentially negative implications for the REC market.”

Cunningham said he also appreciated Tepper’s concern about redundant costs.

“Striking the balance between the onset of a new [market] and moving away from the old one in a timely fashion so that we have the certainty that we as consumers in our homes and businesses and industries want from an electrical availability perspective but also from a cost perspective — that’s essential,” Cunningham said.

Could an FCEM address resource adequacy? There is “a lot of promise there to look at [the Forward Capacity Market and FCEM] in a combined fashion and a lot of efficiencies” Fuller said.

“Nothing that is going on with FCEM would alter or diminish the role of ISO[-NE]’s existing programs to maintain resource adequacy and reliability,” Fuller concluded. “The ISO’s capacity market might need to evolve in response to more clean energy with different attributes and characteristics than the fossil-fueled stuff that we’ve all become accustomed to, but those are going to happen whether we have an FCEM or contract-based system. We’re going to have to evolve to a bit of a different system. Nothing here would undermine resource adequacy, even though nothing in FCEM addresses resource adequacy directly.”