Although the pandemic turned this year into one of the most challenging in living memory, the U.S. offshore wind industry put “steel in the water”; the federal government made progress on environmental reviews; and many states ramped up their clean energy and procurement targets.

But growth challenges are starting to appear as several large projects move toward completion in the mid-2020s, putting pressure on transmission capability and supply chain infrastructure, according to federal and state officials.

So heard 150 participants on Wednesday at the eighth Annual New England Offshore Wind Conference hosted by the Environmental Business Council of New England (EBCNE). Following is some of what we heard.

Federal Perspective

“The big item for 2020 is that we have steel in the water in the federal [Outer Continental Shelf],” said James Bennett, manager of the Renewable Energy Program at the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM), referring to two 6-MW turbines in a pilot project on a site leased by the Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy.

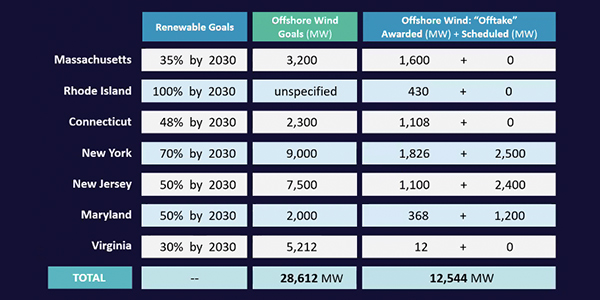

BOEM currently has 16 leases and is looking at other areas as well, while states have gone beyond goals and have identified about 12 GW of offtake, he said.

“It’s not just the leasing and offtake, it takes a substantial development of the industry, including port facilities, testing facilities, academic programs have sprung up, particularly up and down the East Coast, and we have industrial facilities and industrial synergies available through the offshore industry in the Gulf of Mexico,” Bennett said.

BOEM has 10 construction and operation plans (COPs) under review now and anticipates another five or so in the near future, he said.

“We have issues that are starting to develop with regard to transmission and whether or not the system we have in place is as effective as it could be,” Bennett said.

“Navigation, of course, is probably the single biggest definer of what areas are even available for offshore development, and commercial and recreational fishing has been a key issue that we’re in the process of working through,” he said. “We’re anticipating a very active decade ahead.”

BOEM’s assessment of offshore wind development on the East Coast as of Dec. 2 | BOEM

BOEM in November announced a one-month delay in Vineyard Wind’s final permitting, now scheduled for mid-January, with another delay announced this week by the developer due to a change in turbine design.

“Our programs have been very aggressive in anticipating movement on these projects, and we run into some delays, but we continue to move along. South Fork is the next project we’re working on for the environmental impact statement to move towards a record of decision. We’re also looking at the New York Bight, in addition to the lease we issued, the Empire Wind project, and we anticipate moving on additional areas and now have established the Gulf of Maine Task Force … and are also looking at the Carolinas and out on the West Coast and Hawaii as well.”

Asked whether BOEM plans to open an office in the Northeast, Bennett said, “We believe that having our offices where the developers are would be a very good thing, but there are no concrete plans at the moment. It’s one of the things we’ll be looking at with the change in administrations. … We’ve been surprised during COVID at how much can be done remotely.”

States Ponder Shared Tx

“We are very close to issuing the draft of our integrated resources plan for our state … which enables us to track our progress in meeting our state public policy goals,” said Commissioner Katie Dykes of the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection. “As a preview, we’ll be announcing in that plan that we are well on our way to meeting that 100% zero-carbon electric grid target by 2040, based on a whole portfolio of different resources, but recent commitments to offshore wind make up a really critical part of our state’s progress.”

Last year’s 800-MW Park City Wind project selection was the largest ever renewable procurement in Connecticut history, and the state has plenty of precision manufacturing to help develop a domestic supply chain for OSW and hopefully counteract the economic downturn inflicted by the pandemic, she said. For example, Park City will help build up the Port of Bridgeport, and the contract for 304 MW from Revolution Wind will help develop the state pier in New London.

“We were really pleased when Gov. [Ned] Lamont joined with four other New England governors to announce a vision statement that our states are working to implement that calls for a new, regionally based market framework,” Dykes said. (See States Demand ‘Central Role’ in ISO-NE Market Design.)

“I’m excited to share the work that we’re doing at this foundational stage of thinking about market designs that can work into the future to better catalyze the efficient deployment of renewables like offshore wind, and do so in a way that is harmonized with our regional wholesale energy markets,” Dykes said.

States will organize technical meetings in the new year and “we will be emphasizing the need for transmission, that our planning for a transmission backbone is critical to ensure that we have onshore and offshore system upgrades that will provide for efficient utilization of the offshore resources being built,” Dykes said.

Massachusetts DOER Commissioner Patrick Woodcock | EBCNE

Massachusetts Department of Energy Resources Commissioner Patrick Woodcock said it is important to maintain short-term progress but address long-term barriers to OSW development.

“We really are seeing that the transmission network will be limited when you see the states’ ambition, and we conducted a technical conference in 2020 that assessed whether there would be advantages to competitively soliciting transmission independently from generation, and we ultimately determined that it is a regional challenge,” Woodcock said. “The challenge is real, but trying to do competitive transmission and address the long-term challenges of stable growth for the industry really does need to be a regional effort done in coordination with Mass. Nixes Separate Offshore Tx RFP.)

The states need to start long-term planning for the OSW industry, Woodcock said, including transmission planning, development of ports to support the supply chain. They also need to answer the question whether “our market structure is positioned to deliver this scale of resources, and I think the answer to that is no,” he said.

The density of lease areas for uptake in New York, Connecticut and southern New England will create limitations that will require upgrades onshore, and questions linger about whether that will be cost-prohibitive and how to allocate those costs, he said.

Dan Burgess, Maine | EBCNE

“Delays in projects have put pressure on our port infrastructure across the East Coast. When you look at the condensing of schedules, it is the mid-2020s where a lot of projects are now planning to be installed, so there’s a scarcity of acreage for portside infrastructure,” Woodcock said. “Lastly, I would never have guessed in 2017 that there is some scarcity for leasing areas, but the interest of New York, Connecticut and New Jersey has really put pressure on our leasing area, which reinforces why we need to start planning for commercial leases in the Gulf of Maine.”

Dan Burgess, director of the Maine Governor’s Energy Office, said the state wants “to work closely with BOEM and make sure that whatever happens in the Gulf of Maine takes into consideration how important the fisheries are to our state. The lobster industry in particular is a big part of our heritage, but also a big part of our economic picture for the coastal communities.”

Developer Updates

Nathaniel Mayo, director of public affairs for Vineyard Wind, said the project the previous day had announced a supplier agreement with General Electric for 13-MW Haliade X turbines, supplanting a previous deal with MHI Vestas.

“There’s a lot of moving parts to that, the most notable of which from the development side being that we are now anticipating 62 turbine locations (down from 84), further shrinking that footprint and really capitalizing on a product from General Electric,” Mayo said.

The change in equipment necessitates a temporary withdrawal of the COP for some internal due diligence, which “will add a few weeks of additional delay to our work, but it’s been a long road and we look forward to completing that and resuming those operations as soon as possible,” Mayo said.

The company still plans to begin construction in the second half of next year and for the project to go online by the end of 2023.

Ruth Perry, Shell | EBCNE

The Massachusetts DPU last month approved contracts for the 804-MW Mayflower Wind project, said Ruth Perry, marine science and regulatory policy specialist for Shell, a co-sponsor of Mayflower Wind Energy with Ocean Winds, a joint venture between ENGIE and EDP Renewables.

The project is slated to go operational in 2025 and to date has completed benthic habitat surveys and export cable routing, and will continue surveys in 2021, Perry said.

Sophie Hartfield Lewis is head of permitting and marine affairs for the 704-MW Revolution Wind project, a joint venture between Ørsted and Eversource that also is scheduled to go online at the end of 2023.

Lewis touted the partnership having chartered the industry’s first Jones Act-compliant, U.S. flagged service operation vessel, a ship more than 260 feet long that Edison Chouest Offshore will build at its three shipyards in Florida, Louisiana and Mississippi.

Sophie Lewis, Ørsted | EBCNE

The focus was transmission for Scott Lundin, head of permitting in New England for Equinor Wind US, which partnered with BP on the Empire Wind lease off New York and the Beacon Wind lease off Massachusetts.

New England differs from New York in being a region with six states interconnected electrically. For the Beacon project, Equinor has looked for points of interconnection capable of delivering to New England, New York and New Jersey, he said.

“There’s no perfect solution, so we need to find a concept that will both be technically feasible, commercially viable and also permittable. … So we’re looking for the nexus of where those things come together,” Lundin said. “Within 60 miles we can maintain standard high voltage AC, but beyond that and definitively after 100 miles we have to start thinking about reactive compensation and consider DC.”

Scott Lundin, Equinor Wind | EBCNE

For the Beacon project, 60 miles reaches Cape Cod, but all the main load centers are outside the 100-mile radius, so “DC technology satisfies some of these regional transmission concerns and challenges,” and also requires less cabling, Lundin said.

The Southeastern Massachusetts region of ISO-NE is challenged to take much more power, so “where we can interconnect in one state but deliver power to another presents some opportunities here,” Lundin said.