The authors of a new report detailed on Monday how, in the absence of action by Congress, the U.S. can build the transmission lines needed to accommodate the thousands of gigawatts in new renewable generation coming online in the next few decades.

Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy (CGEP) hosted a webinar on the paper it published jointly with the New York University School of Law’s Institute for Policy Integrity.

Michael Gerrard, founder and faculty director of Columbia’s Sabin Center for Climate Change Law, moderated the discussion. He noted that President-elect Joe Biden campaigned on a goal of a carbon pollution-free power sector by 2035, and the U.S. power sector is now 38% carbon free, about half from renewable and half from nuclear.

Clockwise from top left: Michael Gerrard, Columbia University; Sam Walsh, Harris, Wiltshire & Grannis; and Justin Gundlach, Institute for Policy Integrity | Center on Global Energy Policy

“Moving from 38% to 100% will require an enormous increase in renewable generation capacity from the current 1,100 GW, to about 3,000 GW,” Gerrard said. “Much of this new generation will be in areas that are far from where the power is needed, so the massive program of renewables construction will have to be accompanied by a massive program of new transmission, and we need the grid to have much greater functionality in many ways than it does now.”

Melissa Lott, CGEP senior research scholar, said investments in the grid have been lagging, despite the need.

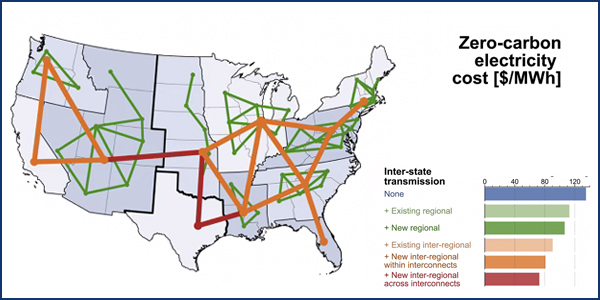

“If we take away all the noise and just focus on the [market] signal, the reality is that we need new, long-distance transmission lines if we want to keep this transition affordable and if we want to do it on a timeline that’s going to both mitigate climate change and protect public health,” Lott said.

States’ Rights vs Federal Authority

If these long-distance transmission lines are so great, then why are they not getting built today? report co-author Sam Walsh, an attorney with Harris, Wiltshire & Grannis posed.

“One important reason, and which is partly the subject of our paper, has to do with state siting laws,” Walsh said. “In general, if you want to build a transmission line, you need regulatory approval from each state that the line traverses, and this state-by-state requirement has proven to be a significant hindrance for long-distance transmission lines that cross multiple states.”

In some cases, this has proven to be an insurmountable barrier when one state has denied approval outright, Walsh said.

Map and chart show the value of inter-regional coordination and transmission in decarbonizing the U.S. power grid. | Center on Global Energy Policy

“The problem is especially acute in the states that are traversed by a transmission line, but which are neither at the source nor the sink of the line,” Walsh said. “Regulators in those states may see little reason to approve a project or to authorize eminent domain for a project if their state is neither going to get the economic benefit of hosting the generation, nor the power itself.”

Congress recognized this problem in the Energy Policy Act of 2005, which created two pathways to get transmission built that do not require state approval. The first pathway is the so-called “backstop” siting authority, said co-author Justin Gundlach of NYU.

Federal siting authority is provided for in Section 216 of the Federal Power Act, which empowers FERC to permit construction of a transmission project where a state agency would not do so, Gundlach said, noting two key features of the regulation.

“The first directs the Department of Energy to designate National Interest Energy Transmission Corridors in appropriate locations, and the second gives FERC backstop permitting authority within those borders, meaning there — and only there — FERC can displace a state’s permitting authority,” Gundlach said.

Congress also limited the commission’s authority by requiring that it must establish that a project meets various public interest criteria.

DOE designated two corridors in 2007: one in the southwest and one in the mid-Atlantic. Their legality was challenged by states, their utilities and their utility regulators. In 2011 the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals vacated both designations, saying the department erred in not consulting the states about its study of the issue prior to the designations.

Since 2011, DOE has not recommended any further corridor designations, so the authority has sat dormant, Gundlach said.

The authors make 20 recommendations. “First, DOE should revise or supplement the 2020 congestion study that it just issued in the fall,” Gundlach said. “For instance, the initial version of this study only identifies instances of present congestion, whereas we think it ought to identify instances of both present and foreseeable future congestion.”

The authors also recommend that the department should designate one or several new corridors.

“When doing so, DOE should prioritize corridors that connect large, constrained renewable resources or potential to load, and recognizing that even just designating an area can make parties with an interest nervous, we think DOE should try to confine its corridor designations, in contrast to the two from 2007, to avoid a groundswell of opposition in locations where it’s unlikely that you’re actually going to see a project.”

Insiders’ View

David Hill, CGEP fellow and a member of the NYISO Board of Directors, found the paper well researched and liked its overall approach. “It doesn’t just complain; it’s got very detailed recommendations, and I think that’s excellent and that it deserves serious consideration.”

Hill said that relevant sections of EPAct05 “are very powerful authorities, and they haven’t been used to their full extent, and there’s a lot more that they could be used for and should be used for.”

He recalled that he was involved in the designation of the two transmission corridors when he was general counsel at DOE.

“I know the courts decided that we didn’t do that right, but we thought very carefully about” designating such broad corridors, Hill said. It ended up being problematic, but narrow corridors would have entailed other significant difficulties, he said.

While the authors suggest that the DOE ought to delegate its authority to FERC to help expedite the process, it’s clear that is not what Congress wanted, Hill said. Congress “knew very well what the functions of DOE were” and separated them from those of FERC, he said.

Former FERC Commissioner Cheryl LaFleur, now a CGEP fellow and member of the ISO-NE Board of Directors, agreed that more transmission is needed and that state siting and permitting authority — coupled with the influence of incumbent utilities that may oppose new lines coming through their territory — have been a major barrier to long-distance transmission across multiple states.

Clockwise from top left: Michael Gerrard, Columbia University; Consultant Lauren Azar; Cheryl LaFleur, ISO-NE; Rob Gramlich, Grid Strategies; and David Hill, NYISO | Center on Global Energy Policy

“I have testified in Congress more than once that Congress should rewrite Section 216 to restore effective FERC backstop siting authority, so you can see how effective that has been,” LaFleur said. “Given the unlikelihood of congressional action, I think this paper could not be more timely.”

While effective backstop authority could help new transmission get sited and built, even the mere threat of exercising such authority could encourage states to work together, she said.

“I do think, however, that FERC backstop authority would not be a silver bullet … and we can expect that states that are opposed to transmission lines will find a way to use their existing authority … to make life very difficult for project sponsors,” LaFleur said. “All of this points to the continuing need to satisfy state authorities and citizens that the proposed facilities are in their best interests to really get them on board.”

With a new administration, it’s important that any steps it takes to improve environmental reviews for natural gas pipelines not “spill over and make it harder to build transmission lines for renewable projects,” she said, citing “schizophrenia” on the issue, with people wanting to slow down National Environmental Policy Act reviews for gas pipelines but speed up permitting for renewables.

Grid Strategies President Rob Gramlich said that the country will need two to three times more transmission than it has now, which doesn’t necessarily mean all that many new lines.

“Solar can be done closer to load, so you don’t see much congestion, but that is a temporary dynamic. … Soon you’ll see solar congestion,” Gramlich said. “We need these lines built now for the end of the decade when we’ll really need it.”

Independent consultant Lauren Azar said that beside the siting challenges, “one of the key problems we have now is the weak nexus between the parties who would like to develop a national transmission plan and those who could actually get it built,” suggesting that President-elect Biden convene the grid operators, FERC commissioners and state governors to work on the issue.