A new report explores ways for New England to overcome the growing conflicts between states’ clean energy goals and the functioning of ISO-NE wholesale markets.

The “Pathways to the Future Grid Process” report, part of New England’s Future Grid Initiative, focuses on four approaches that could potentially smooth tensions between the states and RTO. It was presented to the NEPOOL Participants Committee last week.

The New England States Committee on Electricity, ISO-NE and NEPOOL commissioned Rutgers University Professor Frank Felder to review “a multitude of potential pathways” for resolving differences and assess tradeoffs “between achieving the clean energy policy objectives of the New England states and maximizing the benefit of efficient, regional wholesale markets.”

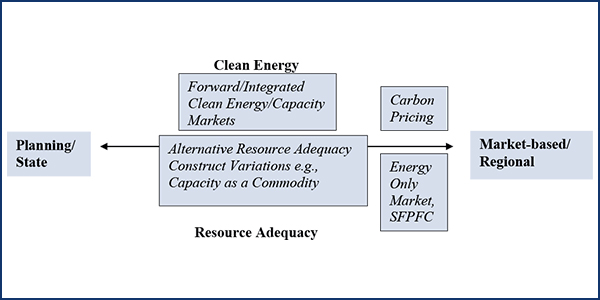

Felder identified four approaches that have been thoroughly discussed in more than a dozen presentations to the PC: a Forward Clean Energy Market (FCEM) or Integrated Clean Capacity Market (ICCM), an Energy Only Market (EOM), carbon pricing and alternative resource adequacy constructs (ARACs).

Felder’s report points to “the importance of defining the criteria for determining the types and quantities of balancing resources needed to reliably plan and operate the regional power grid as the penetration of renewable energy resources increase.”

Most New England states are pursuing aggressive decarbonization. They have goals or policies that envision replacing existing power generation with variable renewable energy resources “whose output is intermittent, and many of these new resources, such as offshore wind, are likely to be at different locations than existing power plants.”

A further challenge for ISO-NE is the minimum offer price rule (MOPR) for new resources bidding into its capacity markets. Although the MOPR addresses potential adverse impacts from out-of-market, state-sponsored contracts on price formation in the competitive wholesale markets, it also prevents state-sponsored resources from clearing the Forward Capacity Market (FCM) and being counted toward the RTO’s resource adequacy requirements.

Felder wrote that New England states “would like to achieve their specific policy objectives cost-effectively, whereas wholesale electricity markets are designed to maximize economic efficiency.

“Although there is some substantial overlap between the states’ objectives of decarbonization and environmental enhancements, economic development, and political acceptability, and the objective of efficient, regional wholesale electricity markets, these objectives are not necessarily reconcilable.”

Comparing Pathways

Felder said the four pathways cut across two comparative frameworks: regional vs. state-specific measures and planning vs. markets. For example, carbon pricing and EOM represent pathways consisting of regional measures paired with a market-based solution. Planning refers to the process of states setting types, quantities and timing of clean energy investments, whether through specific mandates or market mechanisms. By that description, FCEM, ICCM and ARACs are more planning-based than carbon pricing and EOM.

Of the pathways identified, FCEM, ICCM and carbon pricing are primarily directed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions. EOM and ARACs are different ways to provide resource adequacy, although some ARACs are directed at advancing or supporting states’ clean energy objectives.

Both carbon pricing and EOM pathways rely on short-term, wholesale energy prices — augmented by longer-term forward bilateral markets — to drive capital investment decisions. The FCEM and certain ARACs provide longer-term commitments as part of their constructs. However, the report warned that stakeholders should carefully consider whether these constructs would withstand FERC Orders End to ISO-NE Capacity Price Locks.)

More on Carbon Pricing

The report explores alternatives to using FCEM or ICCM to acquire clean energy resources via regional market mechanisms. One alternative would supplement the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) carbon price with an additional regional carbon cost, a move favored by ISO-NE and adamantly opposed by the states. This could be achieved through net carbon pricing, which would require agreeing on a social cost of carbon, subtracting the RGGI price, having ISO-NE charge emitting generators the resulting additional cost of carbon, and rebating the carbon revenue back to load-serving entities. Net carbon pricing mitigates — but doesn’t necessarily solve — the double payment issue that arises when clean resources earn payments from both subsidies and market revenue. It also reduces the states’ ability to control the specific timing and type of clean energy resources to meet their individual policy objectives. And it also fails to explicitly address the balancing resource issue.

Though it is not mentioned in Felder’s report, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Rhode Island and D.C. last month signed a memorandum of understanding to launch the Transportation and Climate Initiative Program (TCI-P), which aims to cut GHG emissions from vehicles by 26% from 2022 to 2032. A cap-and-invest program like RGGI, TCI-P is another step away from carbon pricing in three New England states. (See NE States, DC Sign MOU to Cut Transportation Pollution.)

The report is available for comment until Jan. 22, and all comments will be publicly posted on the NEPOOL website. Felder concluded that detailed evaluations of the pathways will be necessary in 2021, including potential quantitative analysis, which will require greater specificity regarding design and the interaction with other regional policies such as transmission planning.