A significant amount of energy storage capacity is underused by the grid in New England, said Alicia Barton, CEO of FirstLight Power.

Deregulated wholesale electricity markets “do a terrible job of valuing storage right now,” Barton said Wednesday during a webinar hosted by the Northeast Energy and Commerce Association.

Despite the large merchant assets FirstLight has as a renewable energy provider with storage capability, the company is delivering only a fraction of the energy that it could be to the grid, Barton said.

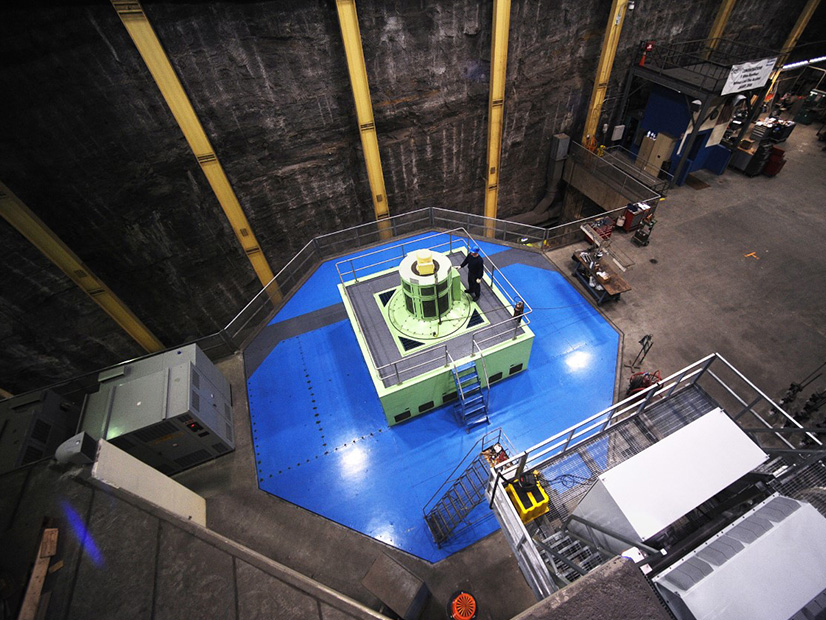

The company’s 1,200-MW Northfield Mountain pumped-storage hydropower facility is compensated for electricity production and ancillary services.

“It’s treated essentially as a merchant fossil generation asset,” Barton said. The storage facility also provides large-scale backup power. FirstLight can dispatch the entire facility in less than 10 minutes.

But the New England market does not distinguish between peak and off-peak hours, so the electricity FirstLight produces all generates the same renewable energy certificates. The current market structure in New England also does not differentiate the values of short- and long-term energy storage.

In addition to the absence of a valuation system for energy storage, the existing markets were “never really designed for flexibility and the use cases that we’re developing now,” said Julia Frayer, managing director of London Economics International.

There is a mismatch between what will benefit the market and society, such as the long-duration storage of clean energy, and what private investors are able to monetize.

“It is an urgent issue to fix,” Barton said. State climate mitigation laws, such as those in Massachusetts and Connecticut, rely significantly on energy storage to achieve net-zero emissions but lack specificity on the types of energy storage.

A regulatory or policy framework that provides consensus on how to value energy storage and benefit ratepayers in the market, not one particular company, is one solution, said Ramya Swaminathan, CEO of Malta Inc.

“Making a push on figuring out what that tool is and how it applies in the context of New England or a particular state jurisdiction would pay itself off in multiples,” Swaminathan said.

The industry also needs a storage investment tax credit, which is “far overdue,” Barton said.

President Biden’s push for infrastructure reform makes the coming months and years an “unprecedentedly open time for making the case for storage,” Swaminathan said.

In the wake of a catastrophic winter storm in Texas that wiped out power for millions in the state, New England has a choice to make on how to move forward with energy infrastructure.

Barton said there is a “healthy number” of fossil fuel resources that can be retired and repurposed to connect solar and storage hybrid plans.

“There’s a lot of innovation that can happen,” she said.