By Rich Heidorn Jr.

The results of PJM’s 2018 Base Residual Auction were “not competitive” and illustrate the need to change how the RTO sets its capacity offer cap, the Independent Market Monitor said Thursday in its second-quarter State of the Market report.

“The outcome of the [2021/22] Base Residual Auction was not competitive as a result of participant behavior which was not competitive, specifically offers which exceeded the competitive level,” the report said.

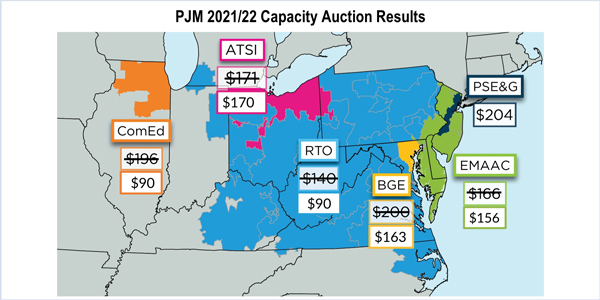

In a separate analysis released Thursday night, the IMM calculated that total revenues from the auction would have been only $6.57 billion had all identified noncompetitive offers been capped at their net avoidable cost rate (ACR). The analysis said offers exceeding net ACR, while permitted by current rules, amounted to “economic withholding” and boosted total auction revenue by 41.5% to $9.3 billion.

Capping at net ACR would have reduced the RTO clearing price from $140.53/MW-day to $90.47/MW-day. “All binding constraints would have remained the same except that the ComEd import constraint would not have been binding and the DEOK import constraint would have been binding,” the analysis said.

It singled out nuclear units, saying more nuclear capacity was offered at higher sell offer prices and fewer nuclear megawatts cleared than in 2017.

Although the IMM has regularly cited structural market power in the capacity market, 2018 was the first time that mitigation efforts failed and market prices were inflated, said Joe Bowring, president of Monitoring Analytics, which serves as PJM’s independent Market Monitoring Unit (MMU).

“I think it’s significant,” Bowring said in an interview. “It’s the result of the fact that the offer cap in the rules is mis-specified and needs to be fixed. We’ve been making that point for a while. But that issue resulted in an impact on this auction.”

PJM issued a statement Friday disagreeing with the Monitor’s conclusions.

“While PJM respects the Market Monitor’s opinion, the facts regarding the 2021/2022 Base Residual Auction are clear. The auction was conducted in accordance with all Tariff-specified requirements and rules, including those rules related to the application of offer caps, and the offers were in concurrence with those rules. The Market Monitor expresses an opinion of what the offer cap should be; the proper forum for such concerns about competitiveness of offers is the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission.”

Grades

For the 2018 BRA, the Monitor gave “not competitive” grades to the aggregate and local market structures, as well as market performance and participant behavior. Market design was judged “mixed.” The Monitor gave the 2017 BRA the same grades for market design and structures but rated both participant behavior and market performance as competitive.

The IMM said this year’s auction failed the competitive test because of the way PJM sets the offer cap under Capacity Performance rules.

“Some participants’ offers were above the competitive level. The MMU recognizes that these market participants followed the capacity market rules by offering at less than the stated offer cap of net CONE [cost of new entry] times B [balancing ratio]. But net CONE times B is not a competitive offer when the expected number of performance assessment intervals is zero or a very small number and the nonperformance charge rate is defined as net CONE/30. Under these circumstances, a competitive offer, under the logic defined in PJM’s Capacity Performance filing, is net ACR. That is the way in which most market participants offered in this and prior Capacity Performance auctions.”

Because net CONE times B exceeds the competitive level in the absence of performance assessment hours (PAHs) — periods requiring urgent actions, such as the dispatch of emergency or pre-emergency demand response — it should be re-evaluated for each BRA, the report said.

Repeating a recommendation it first made in 2017, the Monitor said PJM should develop forward-looking estimates for both B and the expected number of PAHs used in calculating rates for nonperformance charges.

The Monitor said CP rules, which increased penalties for nonperformance, “have significantly improved the capacity market and addressed many of the issues” it previously identified.

But it also said the CP Tariff language is overly rigid. “If the Tariff had defined the offer cap consistent with PJM’s filing in the Capacity Performance matter, the offer cap would have been net ACR rather than net CONE times B,” the report said.

“The bottom line is net CONE times B is way too high, especially when the performance assessment hours are less than 30,” Bowring said.

Of the 1,132 generation resources that submitted CP offers for delivery year 2021/22, 953 (84%) used the net CONE times B offer cap, while 129 (11%) were price takers.

Only eight generation resources (0.7%) requested the Monitor calculate unit-specific ACR-based offer caps. “The fact that so few resources requested unit specific offer caps is further evidence that the net CONE times B offer cap exceeds competitive offers,” the Monitor said.

PJM Disputes

PJM noted that market sellers must declare whether they will use net ACR or the net CONE times B offer cap 120 days before the auction.

“During the weeks where actual offers are submitted and the auction is cleared, the IMM has full visibility into all data relevant to the auction, including resource offers. If the IMM believed that economic withholding was taking place based on submitted offers and preliminary auction clearing results, the IMM could have consulted with the asset owner during that time period,” PJM said.

“If the IMM believes that economic withholding took place, the proper course of action is for the IMM to refer the market seller responsible for such offers to FERC for further investigation. If the IMM believes that the current rules regarding the default offer cap allow for economic withholding, the IMM, like any other stakeholder, can bring forward a problem statement and issue charge to be discussed by the PJM stakeholder body.”

Bowring noted that the issue of the balancing ratio is before the Market Implementation Committee. (See “Balancing Ratio,” PJM Market Implementation Committee Briefs: Aug. 8, 2018.)

PJM also questioned the IMM’s simulation results for nuclear units offering at their ACR. “They are based upon hypothetical offers that could have been submitted on the basis of the IMM’s anticipation of potential performance assessment hours, as well as the IMM’s determination of the appropriate value of ACR to use for certain resources as opposed to their actual going-forward costs,” PJM said. “Given these errors in the assumptions, the simulations bear no direct relevance to any hypothetical auction outcome had different offer-capping rules been in place for this auction.”

PJM spokesman Jeff Shields said the RTO does not agree that there is a problem with the current offer cap. “PJM is supporting stakeholder consideration of proposals that could result in adjustments to the default offer cap, but it is unclear whether a proposal that results in such an adjustment will be approved,” he said.

Should the proper offer cap be net ACR? “No. This assertion is dependent upon an expectation of performance assessment hours,” Shields said. “Whether a given submitted offer was above the competitive level, even though it was within the rules, is a matter for FERC.”

Comparison with 2017

The Monitor’s quarterly report also repeated its concerns over generation subsidies, saying they “threaten the foundations of the PJM capacity market as well as the competitiveness of PJM markets overall.” The Monitor wants to extend the minimum offer price rule (MOPR) to include existing units as well as new resources.

Although the Monitor found the capacity market problematic, it said PJM’s energy markets produced competitive results in 2018. Compared with the first half of 2017, PJM saw the following in the first six months of 2018:

- Energy prices and fuel prices were higher and more volatile, resulting in higher margins for generation types. Average energy market net revenues increased by 160% for a new combustion turbine; 63% for combined cycle plants; 525% for coal plants; 44% for nuclear units; 10% for wind; and 20% for solar.

- Total energy uplift nearly tripled from $49.7 million to $146.4 million.

- Payments for DR programs increased 13.7% to $271.7 million.

- Congestion costs increased by 214% to $896.6 million. Auction revenue rights and financial transmission rights revenues offset only 50.7% of total congestion costs for the 2017/18 period, the first in which new rules required the allocation of balancing congestion to load instead of FTR holders. ARR and FTR revenues offset 98.1% of congestion costs for load during the 2016/17 planning period.

New Recommendation: FTR Liquidations

The report includes two new recommendations. The Monitor said PJM should set a high priority on reviewing how it liquidates FTR holdings, a recommendation prompted by GreenHat Energy’s default in June, when it failed to pay a weekly invoice of $1.2 million. PJM has asked FERC to approve a waiver of rules that require immediate liquidation of a defaulting member’s FTR portfolio (ER18-2068). (See “Default Details,” PJM MRC/MC Briefs: July 26, 2018.)

Bowring said he supports a change in the rules that allows PJM to liquidate the portfolio over a longer period. “These are long-term” positions, he noted.

New Recommendation: REC Transparency

The Monitor also said states with renewable portfolio standards should make the data on renewable energy credits (RECs) more transparent. D.C. and all but five of the 13 states in PJM have a mandatory RPS. Virginia and Indiana have voluntary standards, while Kentucky and Tennessee have no renewable targets. West Virginia repealed its voluntary standard in 2015.

Although FERC has determined that RECs are not regulated under the Federal Power Act unless they are sold in a bundled transaction that includes a wholesale sale of electric energy, RECs affect market prices and the mix of clearing resources, the report said. “Some resources are not economic except for the ability to purchase or sell RECs.”

But data on REC prices, clearing quantities and markets are not publicly available for all states. In addition, RECs do not need to be consumed during the year of production, resulting in multiple prices for a REC based on the year of origination, the Monitor said.

“RECs markets are, as an economic fact, integrated with PJM markets, including energy and capacity markets, but are not formally recognized as part of PJM markets. It would be preferable to have a single, transparent market for RECs operated by PJM that would meet the standards and requirements of all states in the PJM footprint including those with no RPS. This would provide better information for market participants about supply and demand and prices, and contribute to a more efficient and competitive market and to better price formation. This could also facilitate entry by qualifying renewable resources by reducing the risks associated with lack of transparent market data.”

The Monitor said the CO2 price implied by REC prices ranges from $4.74/metric ton in D.C. to $35.41/ton in Pennsylvania, while solar RECs’ implied prices range from $18.07/ton in Pennsylvania to $861.52/ton in D.C.

Those contrast with the 2018 average clearing price of $4.31/ton in the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative and the social cost of carbon, which is estimated at about $40/ton. “The impact on the cost of generation from a new combined cycle unit of an $800/ton carbon price would be $283.56/MWh. The impact of a $40/ton carbon price would be $14.18/MWh,” the Monitor said. “This wide range of implied carbon prices is not consistent with an efficient, competitive, least-cost approach to the reduction of emissions.”