By Christen Smith

Decarbonizing the building sector remains a top priority if Northeast states want to reach their climate targets by 2050, energy experts and regulators said last week.

But state policy efforts have, so far, fallen short of long-term emissions-curbing targets.

“We’ve achieved 17% of where we need to get to in order to reach climate stabilization goals,” Sue Coakley, executive director of Northeast Energy Efficiency Partnerships, said Friday during the Raab Associates New England Restructuring Roundtable at law firm Foley Hoag’s headquarters in Boston. “In recent years, emissions have increased. We really want to get a 76% change. So, we are not on that pathway, and we need to get there.”

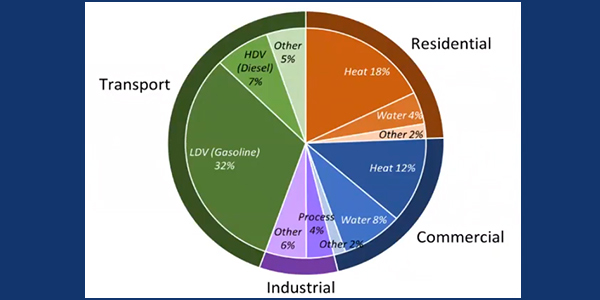

Coakley said the building sector contributes about 35% of total greenhouse gas emissions measured in the New York and New England region — a close second to the transportation industry. “The bottom line is we can’t get to climate stabilization without dealing with it,” she said.

Coakley’s $200 billion solution encourages home efficiency retrofits and replacing fossil fuel heating with cold climate heat pumps in 12 million homes across New England and New York by 2050. She said the $8 billion annual investment over 25 years would decarbonize and improve health, safety and comfort at a far lower cost than the $12.5 billion per year customers currently pay to heat their homes.

To save money, Coakley suggests aligning the projects — estimated to cost anywhere between $5,000 and $30,000 per home — with natural investment cycles of equipment replacement and home improvement. Broad adoption of advanced heat pumps alone would reduce residential and commercial sector heating energy consumption by 67% and “bend the line down” significantly on carbon emissions, she said.

“The numbers are big, but they don’t scare me,” she said. “We do that kind of economic activity in our region all the time.”

It’s not as simple as slapping heat pumps into aging structures erected decades — and sometimes centuries — before uniform building codes existed, said Cutler Cleveland, Boston University professor and author of the “Carbon Free Boston” study.

“It’s the toughest nut to crack,” he said. “We assume there’s just going to be some buildings that it’s really hard to get fossil fuel out of.”

Beyond logistics, Cleveland notes that the poorest 10% of Boston’s households spend up to 25% of their income on fuel and electricity costs, compared to just a few percentage points at the opposite end of the spectrum. Some 16,000 renter-occupied, multifamily households will prove very challenging to retrofit, he said.

“Retrofits and rooftop solar panels can increase gentrification and displacement,” he said. “The toughest buildings to retrofit align with socially vulnerable neighborhoods. The increased value of green homes is great, unless you’re poor, because they can increase the city’s affordable housing problem unless accompanied by explicit policies to protect socially vulnerable populations.”

Eric Dubin, senior director of utilities and performance construction for Mitsubishi Electric Trane HVAC — the leading global manufacturer of energy-efficient heat pumps — said New York City faces similar challenges if it wants to reduce greenhouse gas emissions 80% by 2050. He said research shows that nine in 10 buildings must electrify hot water systems and at least half must convert from oil and natural gas furnaces to high-efficiency heat pumps, he said.

“This is going to be costly,” Cleveland said. “You’re talking about changing a major energy system, the lifeblood of a large industrial city.”

Before it Breaks

Last week in New York, legislators passed the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act, which sets a statewide goal of reaching net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. The bill also codifies the state’s clean energy commitments — 9,000 MW of offshore wind by 2035, 6,000 MW of distributed solar by 2025 and 3,000 MW of energy storage by 2030 — and charts a path to 70% renewable energy by 2030 and 100% clean energy by 2040.

“The legislation … far exceeded my expectations of what good we could do,” said Alicia Barton, CEO of the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority. “We believe it’s the most aggressive climate policy enacted by a major economic market and sets the most aggressive targets in the nation for decarbonization.”

It’s that kind of policy commitment that other state regulators say the region will need to meet its climate goals.

“Heat is a humbling problem,” said Mackay Miller, director of strategy for National Grid. “Yes, we will save emissions at this point, but it will require public policy and investment support — decisive political action and major changes in real estate and customer behavior.”

In California and Massachusetts, policymakers have begun tackling the problem through various energy efficiency programs. California Energy Commissioner J. Andrew McAllister said a new state law the will target spending $200 million over four years to retrofit existing buildings and build greener dwellings — with a focus on low-income housing. Ratepayer funds also contribute $1.4 billion annually for investment in energy-efficient technologies.

Judith Judson, commissioner of the Massachusetts Department of Energy and Resources, said her state’s strategy for curbing emissions 35% by 2030 includes electrifying the building and transportation sectors and promoting conservation and peak demand reduction programs. It’s been a decadelong journey for the state, which first approved energy efficiency mandates in 2008, and has since turned its focus to expanding investments into energy storage, strategic electrification and fuel switching to clean resources. The American Council for an Energy Efficiency Economy ranked Massachusetts No. 1 in the U.S. — eight years running — for its efforts.

Miller argues, however, that renewable gas should factor into any heating decarbonization strategy designed for the Northeast, noting that its climate challenges are too different from a state like California to reasonably compare.

“Heat pumps, hybrid homes, renewable gas from biomass and hydrogen from electrolysis will all play a part,” he said.

Dubin also said it’s important to encourage early retirement of heating equipment rather than waiting for the natural replacement cycle, noting that consumers are less likely to upgrade or transition to more energy-efficient options when dealing with the stress of unit failure.

“I’m that guy,” he said. “How do you motivate me to replace that thing early? We need to do more consumer research and figure out what motivates customers to take action before their systems break down. Encouraging early retirements of old systems would also help move system replacements into times when contractors are not as busy.”