By Robert Mullin

CAISO says it will seek to protect neighboring balancing authority areas if its investor-owned utility members de-energize transmission lines because of wildfire threats — even at the expense of the ISO’s own load.

But the policy of ensuring energy flows to adjoining BAAs during public safety power shutoffs (PSPS) didn’t exactly earn plaudits from the ISO’s own Board of Governors when it was revealed to them Wednesday.

“Not to sound un-neighborly, but why do we feel so strongly that there should not be [PSPS] impact to other IOUs or balancing areas?” Governor Ashutosh Bhagwat asked ISO officials during the board’s monthly meeting.

Bhagwat’s question came after CAISO CEO Steve Berberich and Director of Real Time Operations John Phipps laid out the measures the ISO would take to respond to an “extreme” PSPS event involving high-voltage transmission.

Berberich pointed out that California — which is only now heading into its peak wildfire season — has already experienced three PSPS events this year, compared with seven for all of 2018. (See Fire Season Starts in Calif. with Power Shutoffs.)

“At least some of the utilities have indicated that they very well could de-energize high-voltage [lines] through public safety power shutoff areas. We need to anticipate that this could happen, and we want to make sure everyone knows how we’re going to handle” shutoffs, Berberich told the board. “This is a very important matter. It could significantly impact people across the state.”

It fell to Phipps to describe how significantly. He presented the board with two possible scenarios related to emergency shutoffs in Northern California, clarifying that CAISO’s transmission-owning utilities — and not the ISO — decide when and where to initiate PSPS events.

Under a first, relatively benign, scenario, a wildfire danger limited to the remote northwestern part of the state would prompt Pacific Gas and Electric to de-energize one 60-kV line and a small portion of its distribution system, curtailing 200 MW of customer demand, but having no impact on CAISO’s larger grid and requiring little response from system operators.

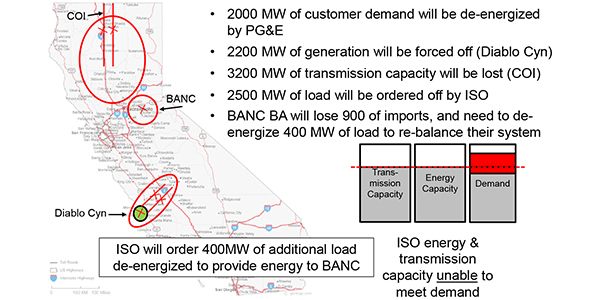

But under a second, “extreme” scenario, Phipps said, PG&E would inform CAISO a day in advance that it would de-energize 230-kV and 500-kV circuits vital to the operation of the bulk electric system.

In that situation, PG&E would curtail high-voltage lines serving the Diablo Canyon nuclear plant on the Central Coast, taking more than 2,000 MW of generation offline. The utility would also be shutting off the portion of the California-Oregon Intertie (COI) running through the fire-prone area near Paradise, curtailing 4,000 MW of import capacity. The Sacramento Municipal Utility District (SMUD), a member of the Balancing Authority of Northern California (BANC), owns part of the COI along with PG&E and other entities.

“So, between the loss of transmission and energy capacity, we can now no longer meet the forecasted demand and reserve obligations for the next day,” Phipps said. “Due to that, the ISO would need to direct approximately 2,500 MW of load reduction to be able to meet our load and reserve obligations meeting N-1 criteria.”

In that scenario, BANC could expect to lose about 900 MW of imports from the Pacific Northwest, forcing it to shed about 400 MW of load, CAISO estimates.

“In order to help BANC avoid doing that, the ISO would make decisions to shed an additional 400 MW of ISO balancing authority load and provide emergency assistance to BANC during the hours that they would be short,” Phipps said.

The rationale for CAISO’s sacrifice is rooted in a set of operating principles the ISO has established to guide its response to wildfire shutoffs.

First among them is to protect the integrity of the BES, “so we will analyze the impact to determine what mitigation measures would need to be taken, including possible additional load shedding to manage N-1 loading issues.”

The second principle is to attempt to limit the impact of a PSPS to the territory of the utility initiating the action.

“So if one of the PTOs [participating transmission owners] is activating a PSPS and it does require the ISO to take actions to mitigate that leading up to the load shedding, we would try to confine that load shedding to that IOU and not let it propagate onto additional, adjoining IOUs,” Phipps said.

The third — and most controversial — principle: to prevent allowing the impact of an “extreme” PSPS to spill over into neighboring BAAs.

“So, in a sense, we would shed additional load so we could provide that energy to the adjacent BA so they could avoid the load shed,” Phipps said.

Doing the Right Thing?

The board bristled at the last principle, questioning the reasoning behind it.

“Is there a sort of joint efficiency argument that it’s just going to be harder to recover, or is this good neighborliness, and how does that interact with the fact that these IOU lines are carrying power to these other balancing authorities?” Governor Severin Borenstein asked.

“The best I could give you is that it’s a good-neighbor policy,” Berberich responded. “I’ve consulted with the CEOs of the IOUs about this [and] they think the best public perception outcome would be to contain [PSPS impacts] to their own PTOs.”

“Even if that means shutting off power to the much larger number of people in the ISO balancing authority?” board Chair David Olsen asked.

“I don’t think that’s what we’re talking about,” Berberich replied, pointing out that CAISO would be only shedding an additional 400 MW of load in the scenario outlined by Phipps.

“I guess it’s not obvious to me what’s the right choice. I understand the politics, but I guess it’s not clear to me the efficiency of shedding that load in the same balancing authority,” Borenstein said, adding that one could make the case that the other BAs that benefit from the transmission lines every day should also bear part of the costs of de-energizing them.

“But you also have to keep in mind that they have no role in deciding to de-energize the lines either,” Berberich said.

“Yeah, that may be, but somebody’s got to make those hard decisions, and I’m sure the utilities are not going to decide to do it because they don’t have to bear 100% of the costs. I guess this is something that is a policy choice that has to be made,” Borenstein said.

Attempting to further illuminate the ISO’s position, Berberich offered another scenario in which PG&E takes out a line that doesn’t affect its own load, while requiring SMUD to shed 200 MW. “That doesn’t sound to me like a very good outcome,” he said.

“If PG&E has to shed a much larger amount of load in order to avoid that, it sounds like neither choice is good, but at some point, having an absolute rule that the PTO’s control area bears unlimited costs before any cost is borne by neighboring BAs seems not the right answer either,” Borenstein contended.

Berberich clarified that there would be no “hard and fast rule” for dealing with PSPS events — that each event would be addressed individually.

“There well could be cases where load has to be shed in adjacent balancing areas,” he said. “Our intentionality is to try to protect them, and our intentionality is to try to keep it perched within the PTO and then within our BA. And if we can’t do that, then it goes to another BA.”

Phipps piped in with a ground-level perspective, speaking from the point of view of a system operator answering an alert that a transmission line is being taken down, not because of a threat to the grid, but because of a “corporate decision to manage the risk of starting a fire.”

“And now I’m going to have to make a call to San Diego [to another IOU] and tell them I need you to shed 200 MW of load. I know you just spent a billion dollars upgrading your system so you wouldn’t have to do this, but I need you to shed load. And now SMUD, by the way, I need you to shed some load also.”

Borenstein, a University of California Berkeley energy economist, pondered whether the complications around wildfire shutoffs were rooted in the broader history of the utility system.

“Because in most other situations, if that other entity had some benefit and ownership of the line [such as the COI], they would also have some co-liability in the line,” Borenstein said.

Instead, PG&E is “solely liable” for any wildfires sparked by the line within its service territory, leaving it as the sole decision-maker regarding operation of the line, despite having a contract with the joint owner that should — but apparently doesn’t — include a right not to deliver energy in order to avoid the costs for wildfire liability, he said.

Borenstein speculated that CAISO’s need for such an “extreme” response to a potential high-voltage shutoff — curtailing ISO load — is an “idiosyncratic outcome” of how the region’s grid has been formed and “the casual relationship that has grown up among adjoining utilities” in the region with respect to risk-sharing for joint projects.

Berberich emphasized the scenario laid out in Phipps’ presentation was an “extreme version” of how the ISO plans to approach wildfire shutoffs, pointing out that utilities have yet to shut down any high-voltage lines running through areas already subject to PSPS.

“Let’s hope we never have to cross this bridge, but in the event we do, we wanted to make sure everybody understood how we’re going to handle it.”