The Biden administration does not have specific plans to coordinate domestic efforts and prove to other nations, as well as U.S. utilities and industries, that the country is fully committed to cutting carbon emissions in half by 2030 and achieving net-zero emissions by 2050.

President Biden “has yet to announce a clear plan for achieving his pledge. He’s announced billions of dollars of new spending on green projects, but I haven’t found any clear plan with specific targets or timetables for translating spending into progress,” Richard Parker, a University of Connecticut School of Law professor and expert on climate law and policy, said in kicking off a breakout panel discussion Thursday at the annual New England Energy Conference and Exposition, held virtually this year.

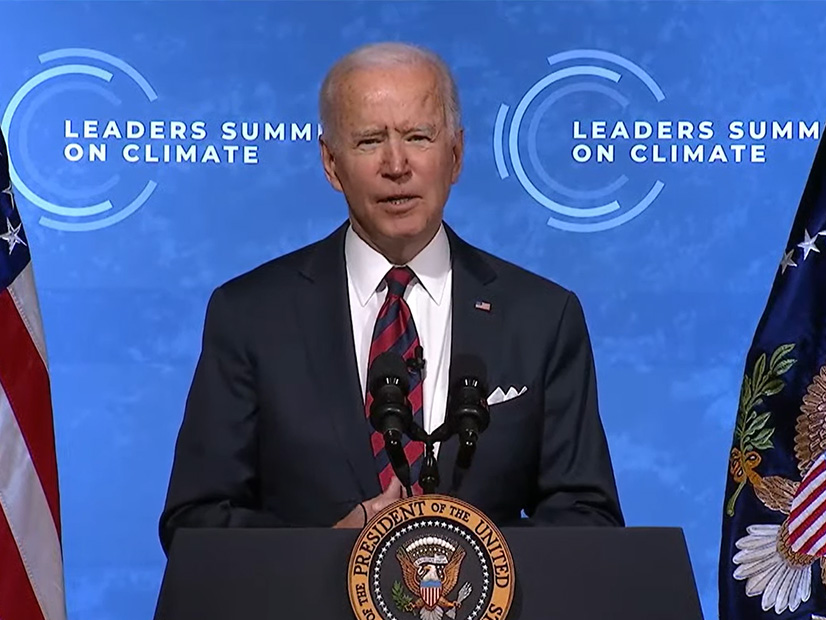

Parker initiated the conversation by recalling Biden’s announcement of the U.S.’ pledge on Earth Day. (See Biden Commits US to Cutting GHG Emissions 50% by 2030.) He also convened a two-day virtual summit that included 40 world leaders.

“I think the main goal of this Earth Day summit,” Parker continued, “was not to elicit immediate concessions from around the world, but to signal that the U.S. is back in the climate game and to promote key nations to undertake their own reassessment of their voluntary commitments under the Paris Agreement — with a goal of eliciting more ambitious pledges from delegates at the 26th meeting of the Conference of the Parties [COP26], which will be held this November in Glasgow, Scotland.”

He noted that the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change concluded in a 2018 report that average global temperatures had been rising over the preceding decade and that steep carbon reductions would be needed by roughly 2030 to avoid a global average annual temperature increase of more than 1.5 degrees C (2.7 degrees F) over preindustrial levels.

Parker was joined by James Cotter, general manager of Shell’s Offshore Wind Americas, and Jason Albritton, director of climate and energy policy for The Nature Conservancy.

Albritton said achieving the kind of carbon reduction envisioned by the administration — most of it in the power and transportation sectors — will require “policy action at multiple levels,” he warned.

“We realize that getting to net zero by 2050 is not going to be easy, and there’s really no one silver bullet,” he said. “Clearly, things have changed dramatically in the last few months with the new administration in the White House, Congress changing hands at the leadership level and, clearly, climate change becoming a central part of the policy discussion where it hadn’t been in past years.” The administration’s goal is “the level of ambition that a lot in the environmental community, the business community, and mayors [and] state governors were advocating … prior to the administration’s announcement. …

“The international community is now looking at the U.S. and what’s going to happen next. We have a commitment, but how are we going to get there? What are we going to do? What policies is the U.S. going to put in place?

“I think what happens in the next few months … are pretty critical. The administration has indicated it is going to put out more detail on their path to get there, but obviously that’s constrained by Congress; it’s constrained by their legal authority. What are the near-term actions is really the next question that I think everybody’s going to be watching,” he said.

Complicating any predictions is that the president’s $2 trillion infrastructure spending proposal is the centerpiece of the administration’s agenda to address climate change, Albritton said.

“The investments and the incentives that are included address a lot of different areas that are relevant to the climate conversation. A key piece is electrification of the transportation sector. That includes investments in charging infrastructure, conversion of fleets [to electric], tax incentives for vehicle purchases to really drive electrification of the transportation sector [and] investment in transit as a way to reduce emissions by increasing transit opportunities.

“There is a big focus on energy efficiency and weatherization both for public buildings and residential buildings as a way to reduce energy use, and a lot of attention to transmission and grid investments, which I think everyone on this call likely knows is critical if we’re going to increase clean energy deployment across the economy,” Albritton said.

While the debate on policy and politics is expected to drag on indefinitely, wind developers are already racing to get steel in the water off the Atlantic Coast. And that could create big problems in the future.

Shell’s Cotter stressed the importance of planning an integrated transmission system now to ensure that future wind farms generating as much as a combined 30 GW by 2030 — and much more later — can be integrated into the electric grid.

“Transmission is one of the most significant hurdles, especially here in the Northeast,” he said. “We should not underestimate how hard it is to physically get cables to the points of interconnection. When individual projects connect, we should ensure that they enable the highest capacity possible both over the beach and into those points of interconnection.”

In other words, allowing each project to plan its own interconnection to the existing transmission system, without an overall transmission plan designed to handle the massive amounts of offshore power that will eventually be generated, could in the long run stymie continued wind development that East Coast states envision.

“Individual projects exist to deliver by themselves, so they can and do make decisions [that] benefit themselves and maybe not the broader industry,” he warned.