Prolonged drought is threatening hydropower production throughout the West, including at the iconic Hoover Dam on the Colorado River, which provides power to Las Vegas and other cities in Arizona, California and Nevada.

The level of Lake Mead, behind the dam, has dropped to its lowest since the lake filled in the1930s. If it keeps dropping, the dam, with a maximum capacity of 2,074 MW, could cease generation altogether — a first.

At a conference on reliability held Thursday by CAISO, the California Public Utilities Commission and the California Energy Commission (CEC), Mark Cook, manager of Hoover Dam with the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, said the lake is now at 1,070 feet above sea level. The dam will stop generating power at 950 feet above sea level because its 17 turbines run too problematically at such low flow levels, he said.

“That’s where we predict that everything is going to run rough enough that we’re just not going to be able to produce any electricity,” Cook said.

“All of our units have a rough zone in them,” he said. “There’s a band … in the middle of the operating region, where we don’t like to operate very long because it’s rough and vibrates and [it’s] hard on the equipment.”

With every foot that Lake Mead drops, the dam loses about 6 MW of generating capacity, he said.

Hoover Dam is generating about 1,500 MW, 25% less than capacity, Cook said.

“Hoover typically generates 4,500 GWh a year,” he said. “In the last year it was down to more like 3,500 GWh, and so it’s in the neighborhood of a 22% decrease [in] … energy output over the course of the year.”

The drought in the Southwest, which some call a “megadrought,” has been going on for years. California has been in a severe drought since last year, and normally wet Oregon has seen less precipitation, too. (See Western ‘Megadrought’ Curtails Hydropower.)

Hydropower generation in California, which normally meets about 14% of peak summer load, will drop by at least 1,000 MW — one-tenth of in-state production — starting this month due to low reservoir levels, said Angela Tanghetti, a CEC electric generation specialist. Generation could be further limited by wildfires in the rugged terrain where most dams operate, she said.

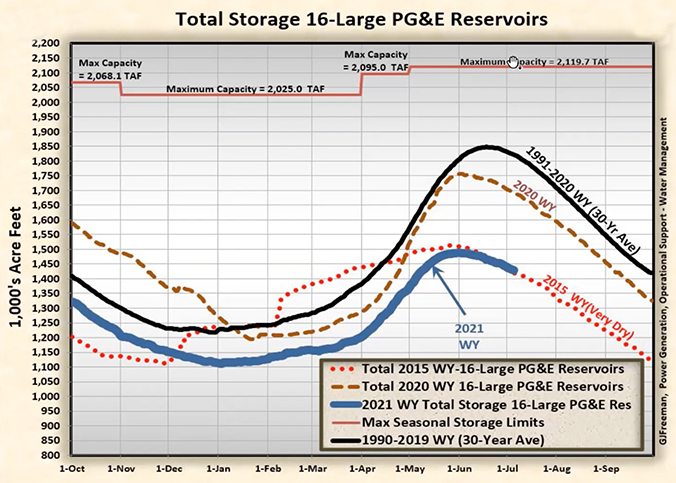

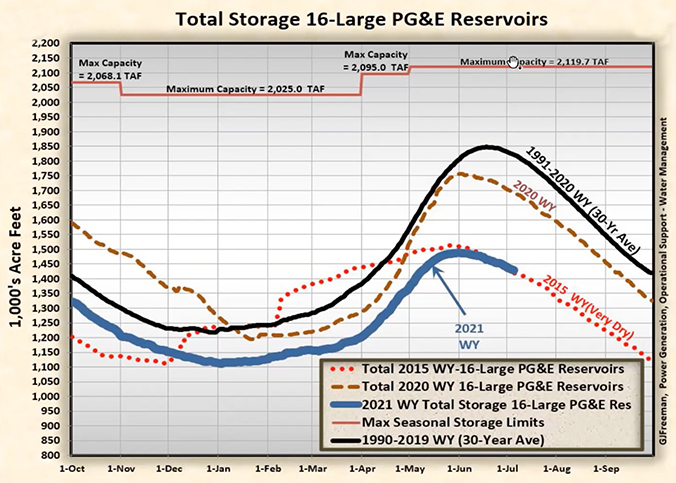

Pacific Gas and Electric, which operates dozens of dams in the Sierra Nevada and foothills, expects to see a big dip in generation this summer. Its 16 large reservoirs account for 95% of its hydro generation, and the storage in those reservoirs is at its second lowest level in the past 40 years, said Eric Van Deuren, director of power generation engineering at PG&E.

The only dryer year was 2015, but only slightly, and 2021 could eclipse it, he said.

“As to the amount of water available in terms of the total generation, we are forecasting for our system …. approximately 45% of historic annual generation, which is pretty much the same number as the percent of precipitation … that we saw within the hydro area.”

Snow water content in California peaked at 60% of normal in 2021 after a similarly dry winter last year, CAISO said in its annual summer resource assessment. The average water level in large reservoirs was 70% of normal earlier this year. (See CAISO Could See More Outages this Summer.)

FERC focused on the California hydropower crisis in its Summer Energy Market and Reliability Assessment. Snowpack, the state’s main source of dry-season water, was critically low at 6% of normal levels May 11. Earlier-than-normal runoff will worsen the situation, FERC said. (See FERC Summer Assessment Spotlights Western Drought Risks.)

CAISO has said low in-state hydro could cause problems meeting peak demand this summer. In a meeting last month hosted by the U.S. Energy Association, CAISO CEO Elliot Mainzer said the hydropower situation adds volatility to resource planning and needs to be accounted for.

Whether drought conditions will abate or continue in future years is a big unknown, Mainzer said.

“The uncertainty … is absolutely something that we now need to bake into our planning,” he said.