U.K. Prime Minister Boris Johnson called on world leaders at the United Nations Climate Conference in Glasgow to phase out gasoline-powered cars by 2035 and end the use of coal-fired power plants by 2040 in the developing world and 2030 in richer economies.

Brianna Fruean, a young climate activist from Samoa, reminded leaders that “climate action can be vastly different from climate justice” and challenged them to summon the “political will to do the right thing, to wield the right words and to follow it up with long overdue action.”

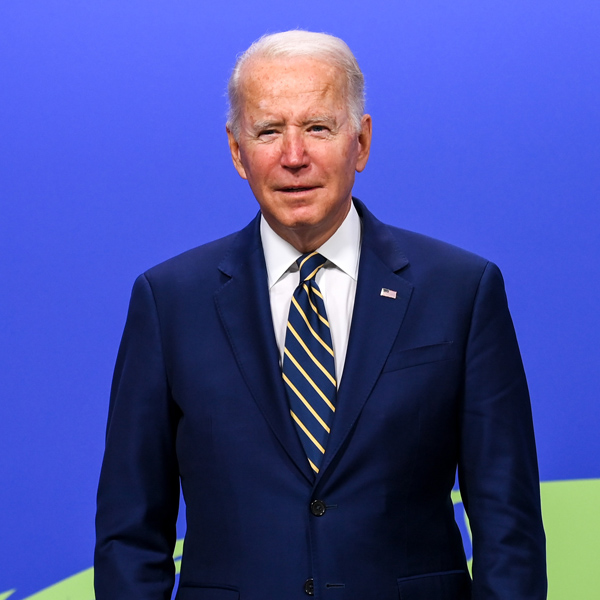

President Joe Biden | COP26

President Joe Biden | COP26U.S. President Joe Biden announced the launch of the Global Methane Pledge — a U.S.-European Union initiative — to cut methane emissions 30% from 2020 levels by 2030. He also pledged the U.S. to make contributions to climate finance for developing nations and called on others to do the same. “Right now, we’re still falling short. There’s no more time to hang back or sit on the fence or argue amongst ourselves.”

The voices coming out of the World Leaders Summit at the UN 26th Conference of the Participants (COP26) on Monday were uniformly urgent and compelling, raising alarms and rallying the world community to immediate action to limit the earth’s warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius — the goal set by the Paris climate accords at COP21 in 2015.

“The six years since the Paris climate agreement have been the six hottest years on record,” said UN Secretary-General António Guterres, speaking at the summit’s opening plenary. “Recent climate action announcements might give the impression that we are on track to turn things around. This is an illusion.”

The UN’s most recent report on existing pledges to climate action — called “nationally determined contributions” — “still condemn the world to a calamitous 2.7-degree increase,” he said. “If commitments fall short by the end of the COP, countries must revisit their national climate plans and policies not every five years, [but] every year, every moment until keeping to 1.5 degrees is assured, until subsidies to fossil fuels end and until there is a price on carbon and coal is phased out.”

Other speakers at the plenary — a mix of world leaders and young climate activists — laid out major themes and pathways for action coming out of Glasgow.

Echoing Guterres, Britain’s Prince Charles called for a carbon tax and “making carbon capture solutions more economical.” Private sector involvement and investment would also be essential, he said.

Mia Mottley, prime minister of Barbados, pushed Western, developed economies to live up to their Paris commitments to provide $100 billion annually to help developing nations transition to clean energy and split the costs of climate adaption 50/50.

“Failing to provide the critical finance … is measured, my friends, in lives and livelihoods in our communities. This is immoral and unjust,” Mottley said. “Are we really going to leave Scotland without the result and the ambition that is sorely needed to save lives and to save our planet?”

U.S. Commitments

Biden’s moment on the COP26 stage came during the first plenary session in which national leaders made their new nationally determined commitments, citing the climate investments and clean energy tax credits in the still-to-be-passed budget reconciliation package and bipartisan infrastructure bill — and the jobs these measures would create.

He also talked up the U.S.-EU Global Methane Pledge, calling methane reduction a simple and “most effective strategy we have to slow global warming in the near-term.” Seventy nations so far have signed on to reduce their methane emissions 30% by 2030, Biden said, while encouraging others to join.

In addition to the U.S. commitment to cutting greenhouse gas emissions 50 to 52% by 2030, Biden also pledged a new level of support for climate finance and adaptation for developing nations — a proposed $3 billion per year. Biden will work with Congress to begin the payments in 2024, according to the new President’s Emergency Plan for Adaptation and Resilience (PREPARE), released by the White House on Monday.

Biden also announced a new report on U.S. long-term strategies for reaching the country’s 2030 and 2050 climate goals, laying out an approach that provides multiple pathways for achieving a 100% decarbonized grid and net-zero economy. Key components range from grid decarbonization and transportation electrification, to a ramp-up of carbon-removal technologies and cutting energy waste so that new technologies can “use less energy to provide the same or better service. The report envisions a changing balance of the core strategies, depending on market and other variables.

“We’re planning for both a short-term sprint to 2030 that will keep 1.5 degrees Celsius in reach and for a marathon that will take us to the finish line and transform the largest economy in the world into a thriving, innovative, equitable and just clean energy engine,” Biden said. The strategy “reinforces the absolutely critical nature of taking bold action within the decisive decade,” he said.

The Republican reaction to the president’s speech was swift and predictable. In an email statement, Sen. John Barrasso (R-Wyo.), ranking member of the Senate Energy and Natural Resource Committee, said the long-term plan would “kill abundant and affordable U.S. energy sources like oil, natural gas and coal that Americans depend on. The White House’s plan is a recipe for disaster. It will result in skyrocketing power bills, less reliable energy and fewer jobs for the American people.”

‘Things Remain Unchanged or Get Worse’

The urgency of the message at COP26 was echoed in the climate communique coming out of the summit of the world’s 20 largest economies in Rome on Sunday. The G20 countries agreed to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees “with immediate action and mid-term commitments,” Italian Prime Minister Mario Draghi said during the group’s closing press conference Sunday. (See COP26 Opens as G20 Finalizes Climate Communique.)

For the first time, Draghi said, the G20 countries recognized the scientific validity of a 1.5-degree target and indicated that carbon neutrality should be met by 2050. In addition, he said, the G20 agreed to phase out global public funding and support for non-abated coal-fired plants after the end of this year.

But speaking at COP26, Draghi said more is needed — “a quantum leap” in climate action, particularly in climate finance. “We must bring together the public and the private sector in new ways,” he said. “We need first and foremost all multilateral development banks and especially the World Bank [to] co-share with the private sector risk that the private sector alone cannot bear.”

UN Secretary-General António Guterres | COP26

UN Secretary-General António Guterres | COP26President Juan Orlando Hernández of Honduras, however, remained skeptical that the strong words of G20 leaders would result in the kind of solid financial help his country needs. Between 2014 and 2021, drought in Honduras “generated annual economic losses of $453 million, which is 1.7% of our GDP, which has given rise to food insecurity and nutritional insecurity,” Hernández said.

Still, Honduras is investing about $2 billion per year in climate action, “only 5% of which comes from loans or grants” he said. “And what is most frustrating is to come to these summits and many others and to see things remain either unchanged or get worse.”

“Even with scaled-up global climate action, it will not be possible to avoid and to reduce all loss and damage from the impacts of climate change,” President Uhuru Kenyatta of Kenya said. “By 2030, economic costs of loss and damage in developing countries is expected to be between $290 billion and $580 million throughout Africa as the most vulnerable continent to the impacts of climate change.”

Kenyatta voiced disappointment that the “special needs and circumstance of Africa” were not included in the official COP26 agenda. “With climate impacts increasing, provisions to help the most vulnerable to adapt, including through increased financial support, should be strengthened,” he said.