Canada has had a price on carbon pollution at the federal, provincial and territorial levels since 2019, but it’s not a perfect system, says Lisa DeMarco, senior partner and CEO of Canadian law firm Resilient.

Carbon pricing in Canada, which reflects the country’s constitutional, federalist structure, is “strange,” DeMarco said during the annual Association of Power Producers of Ontario (APPrO) energy and networking conference on Tuesday.

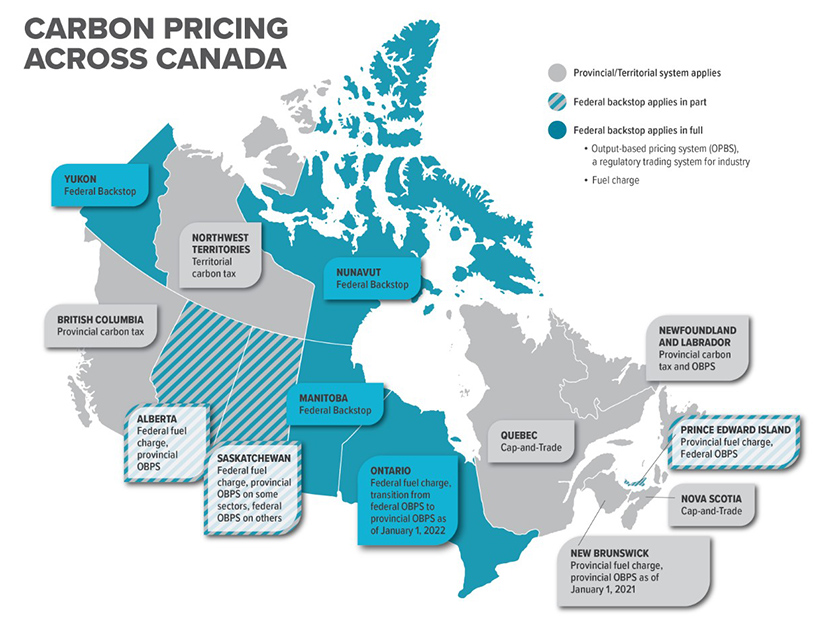

In what is supposed to be a flexible approach, a province or territory can design its pricing system or choose the federal pricing system. However, the federal government sets benchmark stringency standards that any carbon pricing scheme must meet to ensure it is comparable and effective in reducing emissions. If a province or territory decides not to price pollution or proposes a system that does not meet these standards, the federal system is implemented for consistency and fairness.

The federal price has two parts: a regulatory charge on fossil fuels such as gasoline and natural gas, known as the fuel charge, and a performance-based system for industries, known as the Output-Based Pricing System.

Provinces challenged the constitutionality of the federal system, but Canada’s Supreme Court upheld the government’s ability to set minimum national standards for carbon pricing.

Canada is covered entirely by various forms of carbon pricing. In New England, carbon pricing is a political hot potato. However, its high-profile advocates include ISO-NE CEO Gordon van Welie; U.S. Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-R.I.); and New England Power Generators Association President Dan Dolan, who spoke at an APPrO panel on Monday.

With the looming elimination of the minimum offer price rule and a glut of state-sponsored resources entering the market, Dolan said the question is, “How does the market evolve?” New England has aggressive decarbonization and net-zero targets, driven by Massachusetts and Connecticut, which represent more than 80% of GDP and electricity load, Dolan said. Transportation represents the bulk of emissions in New England, twice the amount of any other sector in the economy and “the only one that has actually gone up,” Dolan said.

Power plant emissions, he added, have “fallen off a cliff” for New England, and now the region has “one of the cleanest fleets” in the country.

“Yet that is continuing to [be] where we see more focus put, in large part, because of political expediency,” Dolan said. “But how we then break that curve on the transportation side and bring in heating is going to be key to the overall foundation of where we can power this economy moving forward.”

Crossing the Border

In July, the Canadian government said its carbon price will increase by $15 per year after 2022 until it reaches $170/ton in 2030. However, that could lead to disparities with international trading partners, including the U.S. As a result, Canada is exploring Border Carbon Adjustments (BCAs), which account for differing carbon costs incurred in producing internationally traded goods.

BCAs could include import charges applied to goods from countries that do not have carbon pricing or use a lower carbon price to ensure that they face similar carbon costs. Export rebates can also be provided so that domestically produced goods compete on equal footing in foreign markets, alongside goods from countries with limited or no carbon pricing.

BCAs are not high on the policy docket at the moment, said Mitchell Davidson, executive director of Canada’s StrategyCorp Institute of Public Policy and Economy. The last thing that Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau wants to do “is make things more expensive, even if it’s already doing that in some capacity with carbon pricing,” Davidson said.

Moreover, he said, the additional level of tariffs that would come with BCAs amid rising prices and supply chain issues make it “a low likelihood” for any immediate action.

“Although in the future it is certainly something that the government could seriously consider,” Davidson said of BCAs.

The better policy, said Scotty Greenwood, managing director of Crestview Strategy in Washington, is to have a “North American approach” for energy pricing and carbon transition.

“I think that is more productive to think about how we do that than trying to look at how we compete on something like carbon,” Greenwood said.