FERC last week ruled that New York transmission owners (NYTOs) can exercise a right of first refusal (ROFR) for upgrades to their transmission facilities without being bound by other developers’ cost caps.

The commission’s ruling Friday adds rules for implementing a federal ROFR for upgrades that are part of another developer’s public policy transmission project under Order 1000 (EL22-2-001).

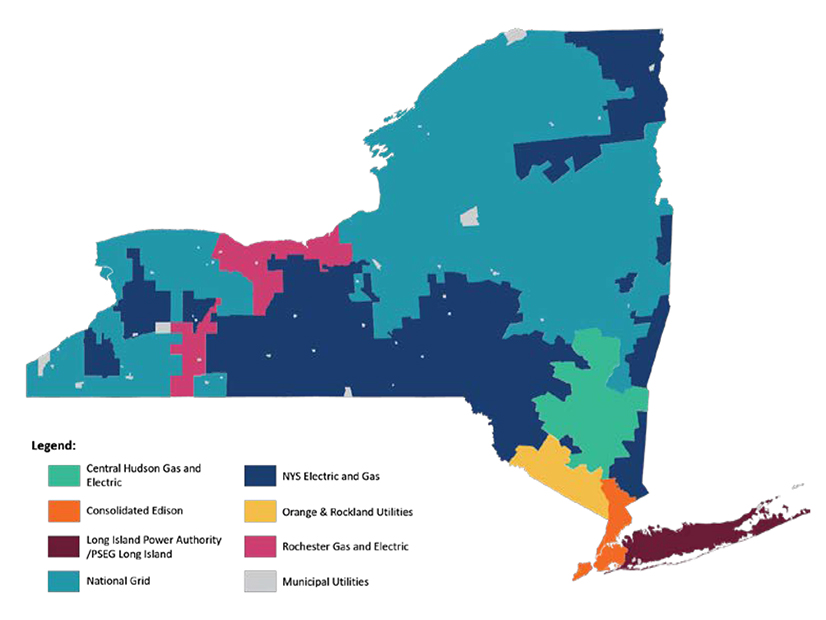

FERC had ruled in April 2021 that the NYTOs — Fortis’ Central Hudson Gas & Electric (NYSE:FTS); Consolidated Edison and Orange and Rockland Utilities (NYSE:ED); the Long Island Power Authority; the New York Power Authority; Avangrid’s New York State Electric & Gas and Rochester Gas & Electric (NYSE:AGR); and National Grid’s Niagara Mohawk Power (NYSE:NGG) — have a federal ROFR under the ISO-TO Agreement and other “foundational agreements” (EL20-65). (See FERC Confirms NYTOs’ Right of First Refusal.)

NYISO filed tariff changes to implement the ROFR in October under Federal Power Act Section 206 — requiring it to demonstrate that its existing rules were unjust and unreasonable — after stakeholders were unable to reach consensus on a filing under the lower threshold of Section 205. (See “MC Nixes ROFR Tariff Changes,” NYISO Management Committee Briefs: Aug. 25, 2021.)

The commission agreed with the ISO that the lack of rules governing the ROFR “will likely result in disputes at the commission and in court, which will cause delays and potentially harm competitive transmission development in New York.” It noted that the commission has already accepted tariff provisions implementing federal ROFRs in CAISO, PJM, SPP, MISO and ISO-NE.

The tariff revisions create separate categories for public policy transmission projects: new transmission facilities and upgrades to existing transmission facilities.

Under the new rules, which are effective as of Oct. 12, 2021, a NYTO will have 30 days to notify NYISO if it does not intend to exercise its federal ROFR for an upgrade. In such cases, the ISO will designate the upgrades to the developer that proposed the project.

Cost Cap Controversy

The new rules revise NYISO’s voluntary cost-containment requirements, clarifying that transmission upgrades will not be subject to any cost cap. The ISO said that requiring a NYTO to accept another developer’s cost cap would undermine the NYTOs’ federal ROFRs.

A group filing as “New York Consumer Advocates” — including the New York Public Service Commission, New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA), New York City and the Natural Resources Defense Council — protested that the lack of cost containment on upgrade projects would subject consumers to higher costs. Transmission developer LS Power separately contended it would undermine competition by causing developers to stop proposing cost-containment measures.

The commission sided with the ISO, saying that “making a developer’s proposed cost cap binding on the NYTO would raise complex implementation issues because the developer’s cost-containment proposal may or may not represent a reasonable expectation of the NYTO’s upgrade costs.”

It added: “While Order No. 1000 required evaluation of competitive proposals that result in the selection of the ‘more efficient or cost-effective’ transmission solution to an identified regional transmission need, it did not mandate that the transmission provider select the least-cost transmission project or apply cost containment for any project.”

FERC noted that four other grid operators — PJM, SPP, MISO and ISO-NE — either do not subject upgrades to a competitive evaluation process or do not allow nonincumbent developers to include upgrades in their proposals.

In a joint concurring statement, Commissioners Allison Clements and Mark Christie said they share the “absolutely legitimate” cost concerns expressed by the PSC and NYSERDA.

Christie went further in a separate statement, noting that NYISO is a single-state grid operator and that its agencies may reject a proposed transmission project because it is “too costly to consumers or that less costly alternatives are available.”

“And, of course, the ultimate recourse for consumers and consumer advocates concerned about the costs of New York’s — or any other state’s — public policies is to the ballot box,” he added.