The Pacific Northwest stands out as an exception to the increasingly dire water supply situation gripping the wider West, boding well for the region’s hydroelectric potential heading into summer.

While regional officials in Southern California last week imposed “unprecedented” water-use restrictions on 6 million residents in the region and the state confronts declining reservoirs and dismal snowpack levels, Washington state faces the summer with dramatically improved water conditions compared with a year ago.

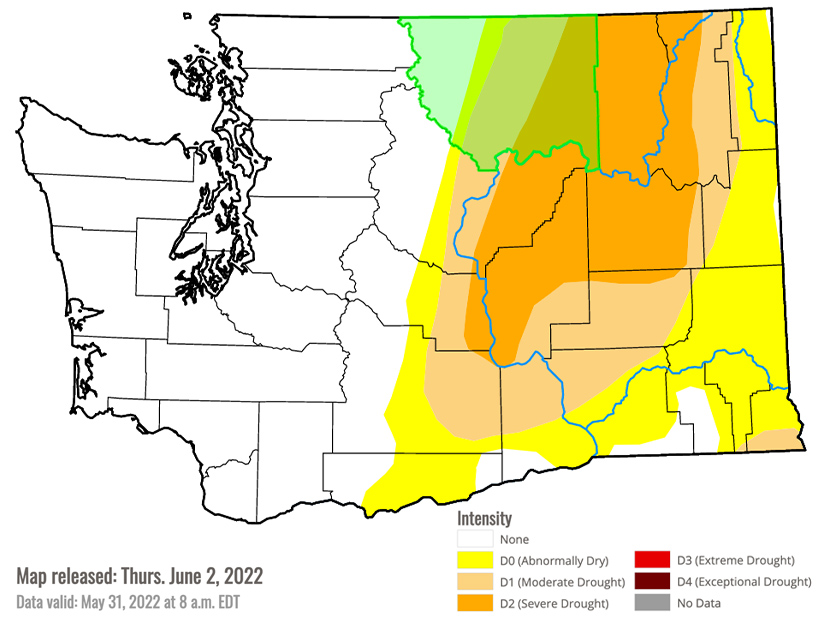

According to data released Thursday by the U.S. Drought Monitor, about 49% of Washington is not experiencing drought conditions, mostly areas from the Cascade Range to the coast. At this point last year, just under 9% of the state was designated as not being in drought after an exceptionally dry spring.

About 17% of the state is designated as being in “severe” drought, compared with nearly 30% a year ago, and no areas are currently in “extreme” drought, versus just under 4% last year.

A “drought” means that rainfall is less than 75% of normal and that hardships are expected because of a lack of water.

Some areas of Central and Eastern Washington still experiencing drought should eventually benefit from the runoff issuing from unusually high snowpack levels at upper elevations. Snow telemetry data from the U.S. Natural Resources Conservation Service show snow water equivalent (SWE) is currently at 215 to 221% of the average in the Upper, Central and Lower Columbia regions, 289% of the average in the Upper Yakima region, and 347% of the average in the Central Puget Sound region.

The improving conditions prompted Washington to dramatically cut back on its drought emergency late last month.

Last July, Gov. Jay Inslee declared a drought emergency for 96% of the state, citing the severe effects of climate change. Last year’s declaration sped up processing for emergency drought permits and allowed temporary transfers of water rights. The cities of Seattle, Tacoma and Everett were not included in the drought emergency because they have significant amounts of stored water.

As of May 26, all of Washington from the Cascade Mountains and to the west were removed from this designation. Most of Eastern Washington, except for four areas, was designated as a drought advisory area. A “drought advisory” means that rainfall is now above the 75% mark but could potentially drop below.

Five watersheds clumped in from areas spread across parts of eight northeastern Washington counties are still in states of “drought emergencies” because they have not received enough rainfall to recover. This land covers about 9% of the state. The drought emergency area covers parts of Spokane, Lincoln, Grant, Adams, Whitman, Stevens, Okanogan and Pend Oreille counties.

“2021 saw extreme temperatures and near record-low precipitation across much of the state,” Jeff Marti, the Washington Department of Ecology’s drought coordinator, said in a May 26 press release. “In 2022, conditions have been much more normal, but we’re still trying to make up a deficit in some places. Extending the drought declaration for these areas will give us more tools to manage water supplies and respond to changing conditions.”

Impacts from last year’s drought that are expected to continue through this summer include low soil moisture, dried-out ponds, earlier-than-normal curtailments for irrigators in Colville, the Little Spokane River and Hangman Creek, and low reservoir storage in Okanogan County, the press release said.

Mixed Conditions in Oregon

To the south, in Oregon, the picture is decidedly more mixed.

Northwest Oregon has emerged from drought after heavy rainfall this year, but conditions are worsening in other parts of the state. | U.S. Drought Monitor

Northwest Oregon has emerged from drought after heavy rainfall this year, but conditions are worsening in other parts of the state. | U.S. Drought MonitorA year ago, the entire state was experiencing drought, with nearly three-quarters designated as being in severe to “exceptional” drought conditions. After a spring of persistent and heavy rains, the northwest corner of Oregon — about 19% of the state, including the Portland metro area and lower Willamette Valley — has emerged from drought.

But the outlook has worsened farther inland, with the portion of Oregon classified as being in exceptional drought (the highest designation) expanding to 11.8%, from 3.5% a year ago, concentrated in the central part of the state east of the Cascades. An even larger portion of the state is in extreme drought, in an area stretching from Eastern Oregon to the south and west, along the California border.

As in Washington, Oregon SWE levels generally far exceed averages for this time of year, with the basin containing the Hood, Sandy and Lower Deschutes rivers at 349% of normal; the Umatilla, Walla Walla and Willow rivers region at 280% of normal; and the Willamette River basin at 219%. The only region with critically low snowpack is the drought-stricken Lake County region in Southern Oregon, currently at 15% of average.

‘A Bit of Good News’

The heavy snowpack in the Northwest should help recharge the region’s extensive network of hydroelectric dams this summer, although some industry observers are still cautious. The largest of those dams, mostly operated by the Bonneville Power Administration, sit in Central Washington or along the Oregon-Washington border on the Columbia River. Others dot smaller rivers in the region, many of them tributaries to the Columbia.

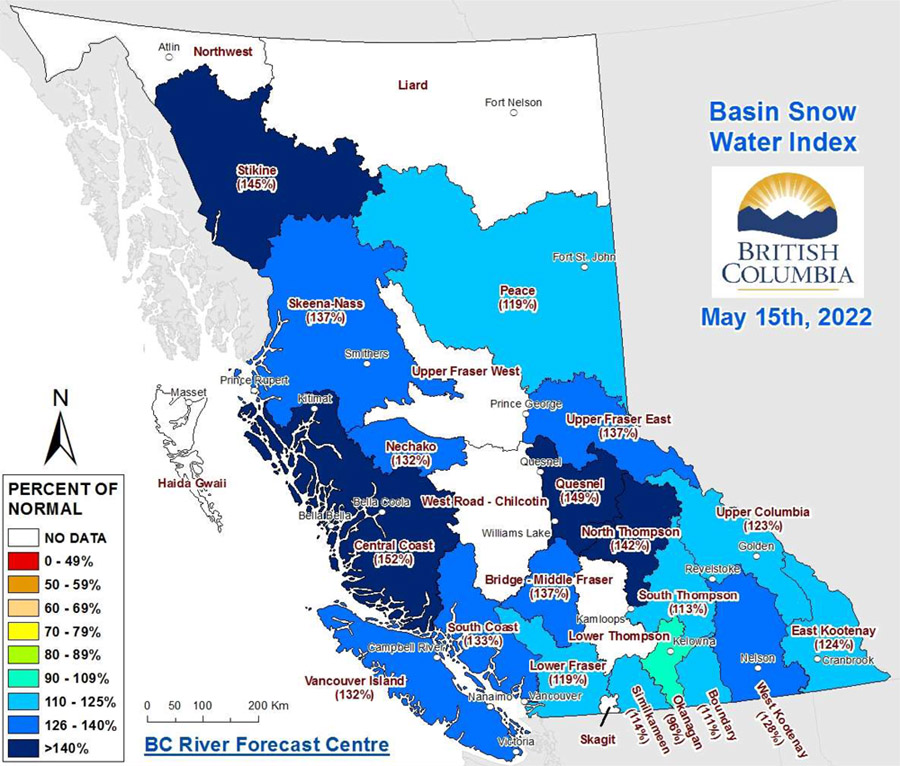

As in its U.S. neighbors to the south, snowpack in the British Columbia is above normal for this time of year. | British Columbia Ministry of Forests

As in its U.S. neighbors to the south, snowpack in the British Columbia is above normal for this time of year. | British Columbia Ministry of ForestsSpeaking at a WECC summer readiness workshop May 24, Amanda Sargent, senior resource adequacy analyst at the NERC regional entity, noted that Pacific Northwest hydroelectric output last year was 14% below the 10-year average, based on data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration. But conditions have changed drastically since the start of the current water year last September, when all of Oregon and Washington were in some level of drought.

“Is it going to be like it was last year? Are we going to see the same effects? It’s impossible to say,” Sue Smith, WECC resource adequacy analyst, said at the workshop. “But I did want to point out that compared to last year, our net generation is higher. It was higher in January, and it was higher in February,” the last months for which data were available.

Another encouraging sign for hydro production can be found in British Columbia — the source of the Columbia River — where government-owned utility BC Hydro operates a massive hydroelectric network on the Columbia and Peace rivers that typically produces ample electricity surpluses exported to the rest of the Western Interconnection.

In “a lot of our service territory right now, the snow levels — or the snow water index, as we refer to them — is quite high, quite healthy,” Brett Hallborg, senior system control manager at BC Hydro, said during the WECC workshop. “So that’s a good news story for BC Hydro and its resource adequacy. But it’s also probably a bit of good news for WECC and its resource adequacy [that] we do have quite a bit of water.”

The most recent data available show SWE at 118% of normal in the Peace River basin and 123% in the Upper Columbia basin.

Hallborg noted that cool weather this spring has delayed this year’s snowmelt, a condition that applies equally to Oregon and Washington.

“And, in fact, just recently in a kind of a new climate change-type storm, we got some fresh snow fall in each of those areas, which is a little unheard of even for us at this time of year,” Hallborg said.