Republican and Democratic legislators reacted warily to New York Gov. Kathy Hochul’s climate and energy proposals during a marathon budget hearing Tuesday.

Hochul administration officials defended her agenda against Republicans who think it is too aggressive and Democrats who think it is not aggressive enough.

The 2023/24 budget Hochul proposed includes policy changes and spending decisions that would bolster efforts to slash greenhouse gas emissions and transition to clean energy. The first checkmark — 70% renewable energy by 2030 — is only seven years away.

Among Hochul’s proposals are:

- a “cap-and-invest” program to cut greenhouse gas emissions;

- authorization for the New York Power Authority (NYPA) to begin developing its own renewable projects; and

- a prohibition on new gas-burning appliances and heating equipment.

Both houses of the state Legislature are held by a Democratic supermajority; Hochul, also a Democrat, has many priorities in common with them but diverges on some of the details of achieving those priorities, sometimes significantly.

Like her predecessors’ executive budgets, her record $227 billion proposal is a starting point for closed-door negotiations, an aspirational wish list that will not emerge intact.

Cap-and-invest

The cap-and-invest proposal was a frequent topic. Some legislators expressed reservations that Hochul’s proposal is short on details on how the program would be designed, how the resulting money would be spent, and how certain large emitters of greenhouse gases would be chosen for exemption from the requirements.

Sen. Liz Krueger, the Manhattan Democrat wielding the gavel during the hearing, pressed Basil Seggos, commissioner of the Department of Environmental Conservation, on how much control the Legislature would have.

Not much, suggested Seggos, who said DEC already has sweeping authority to create such a program.

Krueger wondered if Hochul’s plan is weaker than what was recommended in the scoping plan recently completed for the state’s landmark Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act (CLCPA).

“Look,” she said, “I support this effort, but I’m a little confused about what we’re signing off, particularly in perpetuity; that generally makes me nervous as a legislator.”

Seggos said the state is consulting with stakeholders on what the regulations and structure should be, and it would be premature for him to discuss it. “We will be coming back to the public at a very aggressive rate over the coming five months before we even get into the regulatory phase,” he said.

The deadline for passage of the budget is only six weeks away.

Sen. Michelle Hinchey, an upstate Democrat, alluded to a recurring issue in New York government: Who controls the purse strings? Hochul’s cap-and-invest proposal is short on details, she said.

“It’s hard from our place of responsibility to greenlight an entire program without really understanding — even if we all kind of believe kind of deeply in the foundational points of it — where that’s going to go because historically we have lost lots of money that way. So we want to make sure we’re tracking it and it’s actually going to the places it needs to.”

NYPA Boost

Democratizing the energy sector and expanding public ownership is a goal of numerous advocacy groups, many of which have thrown their support behind the proposed Build Public Renewables Act, which is similar to Hochul’s proposal for NYPA.

But they do not like the way Hochul is proposing to do it, and have dubbed it “BPRA Lite.”

Her budget would not require NYPA to undertake development — only authorize it to do so — and she would give NYPA considerable discretion on how to go about development. Union-friendly provisions of the BPRA also are missing from Hochul’s proposal.

Assemblyperson Zohran Kwame Mamdani, a New York City Democrat, pressed acting NYPA CEO Justin Driscoll on the missing labor provisions. “Why has that language been removed and how do these omissions better position the state to unionize and expand the workforce needed to meet the goals of the CLCPA?” Mamdani asked.

Driscoll replied that NYPA already requires prevailing wages on its projects and is open to project labor agreements. He said a $25 million training fund would be created for new workers.

“I don’t see what’s missing,” Driscoll said.

“Did NYPA or the governor speak to labor before drafting this version of the Build Public Renewables Act?” Mamdani asked.

Driscoll said he could not speak for the governor.

“But for NYPA?”

“I did not personally. I can’t speak for my staff.”

NYPA acknowledged the “great challenge” of building renewables but is committed to doing it as economically as possible, Driscoll said.

NYPA needs to have case-by-case discretion on developing renewable energy projects, Driscoll said, which is why Hochul proposes to authorize NYPA to take such steps, not require it to.

NYPA could undertake small renewable projects on its own but is more likely to partner with other entities on larger projects because of its finite resources, Driscoll said.

Fear Factor

Hochul’s bill calls for a ban on installation of fossil fuel building systems in newly constructed residential buildings up to three stories tall starting Dec. 31, 2025, and in taller buildings starting Dec. 31, 2028. Retrofits in existing buildings up to three stories would be banned starting Jan. 1, 2030, and in taller buildings starting Jan. 1, 2035.There’s no specific ban on gas stoves proposed, but a ban on installing gas systems would at some point begin to limit use of gas cooking equipment.

Sen. Mario Mattera, a Republican representing some of Long Island’s suburbs, said constituents are anxious over being told they will need to replace their familiar fossil-burning fixtures with technologies whose costs, reliability and even availability are still unknown.

“People are frightened right now,” he told Doreen Harris, CEO of the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA).

A similar question had been asked of her earlier, and Harris again acknowledged the challenges facing the state, not least of which is building out electric vehicle charging infrastructure in New York City.

“You’re still not answering the question,” Mattera said. “Is this [reaching the state’s 2030 goals] feasible?”

“Certainly when we look … at the goals in the climate law for 2030, we do see them as feasible,” Harris replied. However, she acknowledged his point about communicating not just the goals for CLCPA but the steps that will be taken to reach them.

“We are not taking away gas stoves, as one example of perhaps misinformation we need to correct,” she said. “Also, we are going about this in a measured and deliberate way that does not create cliffs or specific reasons for alarm. This is a very rational, thought-out plan.”

Long Day of Q&A

The legislators had as little as three minutes each to question the witnesses, and some prefaced their questions with their own thoughts and opinions. So even though the hearing lasted more than 13 hours, witnesses often had time only to dash off half-answers or promise to follow up.

But the Q&A did yield some nuggets of information, including:

- New York’s existing nuclear power plants are central to achieving the state’s goals, and the advanced nuclear technology now in development could also provide cost-effective benefits, Harris said.

- Seggos said DEC will soon request proposals for a consultant to assess the cryptocurrency mining industry, which is under a two-year moratorium on building more of its power-intensive server farms in New York.

- Only about 20% of the 11,000 communal EV charging station plugs in New York are accessible to the general public, Harris said.

Rory Christian, chair of the Public Service Commission, acknowledged complaints about the inability to connect new generation to the power grid but said the PSC is aggressively working on the issue and is on track to have generation and transmission infrastructure in place to accommodate all the electrification planned by 2030.

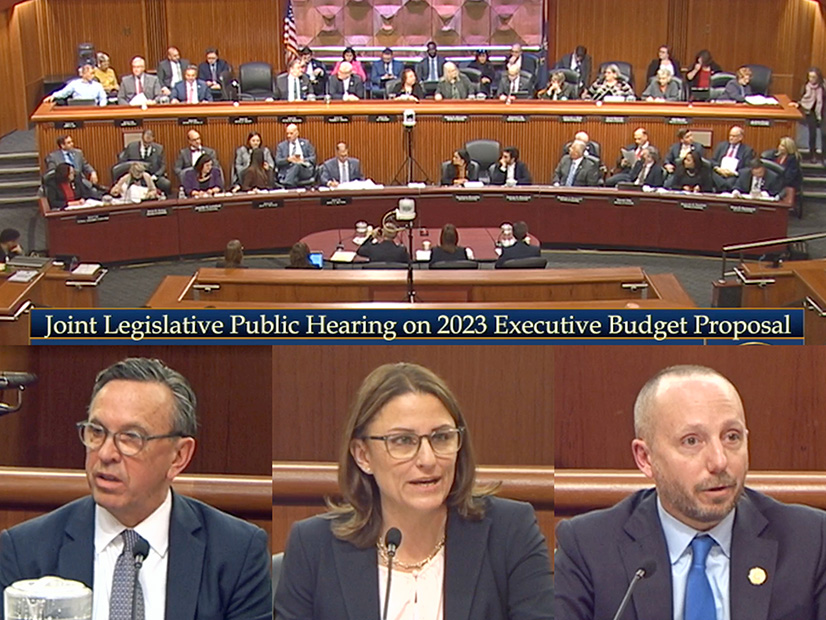

Rory Christian, chairman of the New York State Public Service Commission (left), and Houtan Moaveni, executive director of the New York state Office of Renewable Energy Siting, speak Tuesday at a joint legislative hearing on environmental conservation spending in the 2023-2024 budget proposed by New York Gov. Kathy Hochul. | New York State Legislature

Rory Christian, chairman of the New York State Public Service Commission (left), and Houtan Moaveni, executive director of the New York state Office of Renewable Energy Siting, speak Tuesday at a joint legislative hearing on environmental conservation spending in the 2023-2024 budget proposed by New York Gov. Kathy Hochul. | New York State Legislature

The PSC’s mission and goal is preserving reliability of the power system through the clean-energy transition, Christian said, and if the transition plans are delayed or derailed, the plans will be reworked because reliability will remain paramount.

Hinchey, who chairs the Senate Agriculture Committee and represents a wide swath of farming communities, said there are too few braking mechanisms on development of productive farmland for solar arrays.

“We can’t replace a climate crisis with a food crisis,” she said.

Houtan Moaveni, executive director of the Office of Renewable Energy Siting (ORES), said the state will not meet its CLCPA goals without such integration of uses. He said ORES is looking at the marriage of the two through agrivoltaics but does not want to be prescriptive.

Hinchey thought it would make sense to hold off solar siting on farmland until agrivoltaic technology is mature and available because once farmland is gone, it is hard to get back.

The clock ran out before Moaveni could respond.