Coal-fired power plants nationwide will either have to close by 2039 or use carbon capture and storage or other technologies to capture 90% of their emissions by 2032 under EPA’s long-awaited final rule issued April 24.

The 1,020-page document actually contains four different, “severable” rules:

-

- the repeal of the Affordable Clean Energy rule that the agency issued during the Trump administration;

- greenhouse gas emission guidelines for existing coal plants;

- new source performance standards for gas-fired plants built after May 23, 2023; and

- revisions to the performance standards for coal plants that undergo a large modification, matching the new emission guidelines.

Absent from the package are emissions guidelines for existing natural gas plants, as EPA proposed in May 2023. (See EPA Proposes New Emission Standards for Power Plants.) The agency first announced the change to its proposal in February. (See EPA to Strengthen Emissions Regs for Gas Power Plants.)

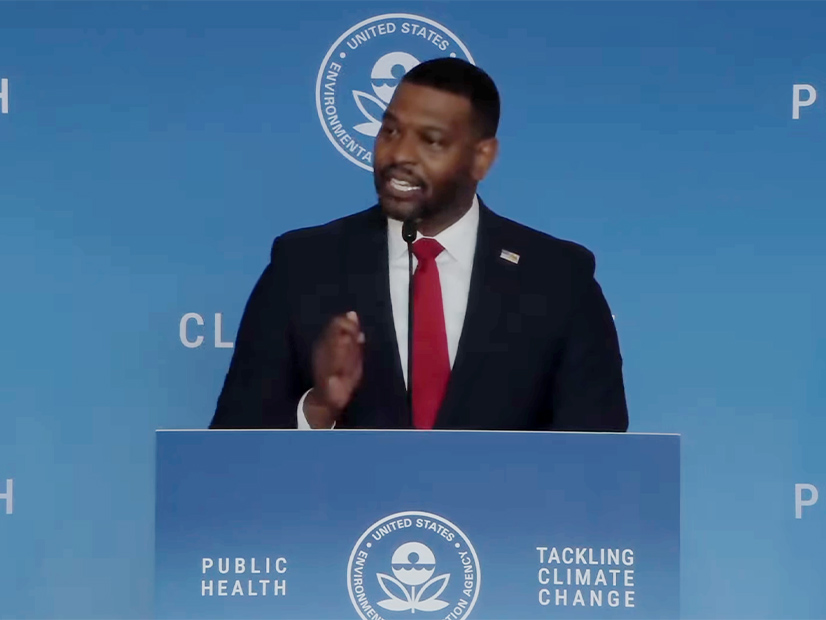

During a press conference April 24, EPA Administrator Michael Regan said those guidelines have been delayed because of feedback from both industry and environmental groups, which pushed the agency to “do better.”

The agency has opened a docket and issued “framing questions to gather input about a more comprehensive approach to reduce greenhouse gases of existing gas combustion turbines in the power sector,” Regan said. “We are committed to expeditiously proposing GHG emission guidelines for those units … and we’re going to do it in a very transparent and engaging way.”

An EPA analysis estimates the rule could cut 1.3 billion metric tons of power-sector carbon dioxide emissions by 2047 and provide climate and health benefits totaling $370 billion, or about $20 billion per year.

“In 2035 alone, that means preventing 1,200 premature deaths, 870 hospital visits, 360,000 avoided cases of asthma symptoms, 48,000 avoided school absences and 57,000 lost workdays,” Regan said April 25 at a public announcement of the rules at Howard University in D.C.

Anticipating pushback from the electric power sector and fossil fuel organizations, Regan said the CO2 rule will not only protect public health but also allow the power sector to “confidently prepare for the future by enabling strategic long-term investment and establishing an informed, multiyear planning strategy.”

“Despite what you will hear and what they will say, we can do it all while ensuring the power sector can provide affordable, reliable electricity for the long term,” he said.

In addition to the CO2 rule, EPA issued pollution-reduction standards for wastewater and coal ash produced by power plants and updated the Mercury and Air Toxics Standards.

“Each of these rules contains transparency requirements, so that the emissions, the discharges and the compliance data are made available to the public, ensuring that power plants are held responsible and accountable for their activities,” Regan said.

“The U.S. is closing in on its goal to cut greenhouse gas emissions in half by 2030,” the Natural Resources Defense Council posted on X. “Now, the EPA needs to finish the job and limit emissions from already built gas power plants that continue to threaten communities and our planet.”

Altered Deadlines

The final rules push up some compliance deadlines and extend others compared to last year’s proposal.

For example, the deadline for coal plant closure or CCS abatement was 2040 in the proposed rule, and new baseload natural gas plants originally had until 2035 to reduce emissions by the 90% requirement, as opposed to 2032 in the final rule.

The rule also provides different compliance levels for existing coal plants depending on whether they intend to operate past Jan. 1, 2039:

-

- Plants intending to operate past 2039 will have until Jan. 1, 2032, to cut their emissions to a level based on a presumption that they will install a CCS system capable of capturing 90% of their emissions.

- The emission cuts for plants planning to close by Jan. 1, 2039, will be based on a presumption that they will shift their fuel mix to 40% natural gas by Jan. 1, 2030.

- Plants with a demonstrable commitment to shutting down before Jan. 1, 2032, will be exempt from the rule.

States will also be able to issue “variances” for individual plants that have “fundamentally different circumstances than those considered by EPA and … cannot reasonably achieve [the] required degree of emission limitation,” according to an agency summary.

The standards for new natural gas plants also vary based on a plant’s expected operation level:

-

- Baseload plants intending to generate at least 40% of their maximum annual capacity will have to comply with two standards: a first phase based on efficient design and operation, and a second phase assuming 90% carbon capture by Jan. 1, 2032.

- Intermediate-load plants planning to operate at 20 to 40% of their maximum capacity will only have to comply with the efficient design and operation standards.

- Plants expecting to operate at less than 20% of their maximum capacity — mostly peaker plants — will have to comply with a standard that assumes their use of low-emitting fuels.

The different levels for coal and natural gas are intended to reflect “the fact that the longer-running and more heavily utilized a power plant is, the more cost-effective it will be to install controls for CO2 emissions.”

States will be required to submit their plans for complying with the final rule within two years of its publication in the Federal Register. Regan said the rule allows for flexibility in state plans, for example, allowing coal and new natural gas plants to exceed the EPA limits if needed to provide short-term emergency power, for example, during an extreme weather event.

State plans can also allow for longer-term flexibility if a coal plant scheduled to shut down is kept in operation to ensure utilities or transmission operators can supply regional reliability. States may also seek one-year extensions to comply with specific standards because of “unexpected delays with control technology implementation that are outside the owner or operator’s control,” according to the summary.

The CCS Issue

The rule acknowledges concerns raised by environmental justice and community groups about EPA’s promotion of CCS as a best system of emissions reduction (BSER) under Section 111 of the Clean Air Act.

While still an emerging technology, CCS has received a range of federal support, with the Department of Energy funding several demonstration projects. These projects also may receive generous tax credits from the Inflation Reduction Act.

EPA argued its carbon pollution standards are “performance standards and do not require the installation or operation of any particular technology. Individual owners and operators will decide how best to meet the requirements laid out in the rule. …

“EPA is committed to implementing its programs and working with federal partners to ensure that where CCS is deployed, it is implemented in a way that considers community input and is protective of public health, safety and the environment.”

Many of the criticisms lobbed in response to the final rules focused on CCS.

“The path outlined by the EPA today is unlawful, unrealistic and unachievable,” Jim Matheson, CEO of the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association, said in a statement. “The rule mandates the widespread adoption of technology that is promising but not ready for prime time.”

“CCS is not yet ready for full-scale, economywide deployment, nor is there sufficient time to permit, finance and build the CCS infrastructure needed for compliance by 2032,” said Dan Brouillette, CEO of the Edison Electric Institute.

The Electric Power Supply Association said the package “relies on unavailable technology and will stymie much needed investment in new, more efficient and cleaner power resources as older units retire.”

“While EPSA welcomed the EPA’s announcement that it had removed existing gas plants from its proposed emissions regulations, the final rule released today is still a painful example of aspirational policy outpacing physical and operational realities,” CEO Todd Snitchler said.