EPA is reportedly poised to propose rules that would require all coal and gas-fired power plants to reduce or capture nearly all of their carbon dioxide emissions by 2040.

The New York Times reported Saturday that EPA plans to release a rule that for the first time would set limits on carbon dioxide emissions from existing power plants.

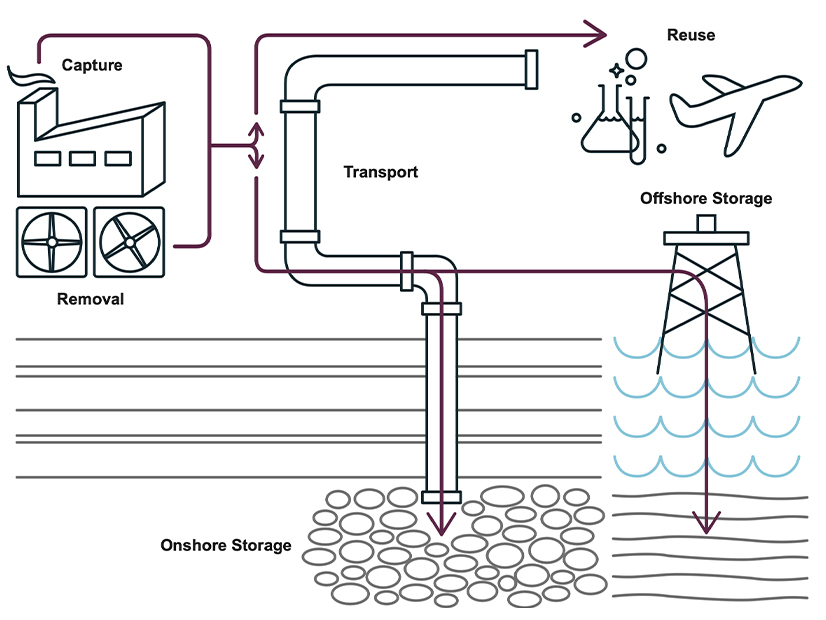

The pollution limits would not be technology specific, allowing natural gas plants to either capture their carbon, or switch to “green” hydrogen that is produced without carbon emissions, according a report in the Times that was largely confirmed by The Washington Post.

While carbon capture has proven expensive on power plants, recent federal legislation, including the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and the Inflation Reduction Act, have set up a comprehensive framework that should enable the wide-scale deployment of carbon capture by 2030, the Carbon Capture Coalition said Monday in releasing its 2023 Federal Policy Blueprint.

The IRA increased federal tax credits for electric utilities that capture their carbon dioxide from $30 to $50/ton of CO2 to $85 to $135.

At a press event announcing the blueprint Monday, the coalition’s Executive Director Jessie Stolark said its wide-ranging membership has not had a chance to coordinate a response to the reported regulations yet. The group has focused mainly on market-incentives to encourage carbon capture technology, she added.

“I really want to underscore that our members agree that deploying carbon capture technologies in the power sector is absolutely critical to reducing emissions, as well as providing a more affordable, reliable baseload power and a deeply decarbonized energy grid,” Stolark said.

Shannon Heyck-Williams, vice president of climate and energy for the National Wildlife Fund, who participated in the coalition event, said her group welcomed news of EPA’s plans.

“WF is very excited to see this rule come out,” she said, saying CCS technology could have a role to play with some natural gas plants. “Obviously, we can’t adequately tackle climate change unless we’re really dramatically reducing power sector CO2 emissions. And, frankly, we could get to zero. That’s the goal.”

In response to EPA’s request last year for comments on how it should handle emissions from “electric generating units,” the Edison Electric Institute spelled out a way that it said could encourage cuts without mandating specific technologies.

EEI noted that for now the main way to cut emissions from power plants is to make them more efficient, with both hydrogen and carbon capture technologies not quite ready for mass deployment.

“Both hydrogen co-firing and CCS technology face a number of other challenges that will need to be overcome to enable commercial scale use throughout the industry,” EEI said. “Government and industry are investing in addressing these cost, technology, and infrastructure challenges. With that investment, there is reason to be optimistic that these challenges will be overcome in this decade.”

EEI argued that any new rules should be flexible, saying that hydrogen and carbon capture might work in some regions of the country but be infeasible in others. The agency should allow new power plants to retrofit those technologies when they become viable.

EEI also suggested that the agency would benefit from shifting to mass-based tonnage requirements for regulated units. Previous emissions rules have used a rate-based system.

“Since decreases in (or limits of) a unit’s capacity factor have a direct impact on its CO2 emissions profile, states, EPA, and units can employ a mass-based approach to leverage the emissions reductions benefits of a decrease in capacity factors, while preserving maximum operational flexibility to support overall system reliability by preserving the availability of units for resource adequacy, particularly during extreme weather events or other emergency conditions,” EEI said.

“We’ve got to go with a scale, we’ve got to go with the pace like never before,” U.S. Deputy Secretary of Energy David Turk said at the coalition’s webinar Monday. “My former colleagues at the [International Energy Agency] projected that by 2030, we’ll need to lock away roughly 30 times as much carbon as we’re currently managing, and nearly quintuple that by the middle of the century.”

DOE has made $10 billion available for a suite of carbon management applications, including the recent request for six demonstration projects at coal and natural gas plants, he added. DOE is also working with the Treasury Department to finalize the expanded 45 Q tax credit for carbon capture, said Turk.

EPA’s power plant rules would not be finalized until next year, following a public comment period. The Biden administration hopes to complete the regulations before Republicans could upend them by winning control of Congress in 2024. The Congressional Review Act allows a new Congress to reject regulations finalized within 60 days of the previous Congress.

The administration also is attempting to craft the rules to withstand certain court challenges.

The Supreme Court ruled last June that the Obama administration’s EPA failed to provide “clear congressional authorization” for its Clean Power Plan, which would have compelled generation shifting to reduce carbon emissions from coal-fired power plants. (See Supreme Court Rejects EPA Generation Shifting.)