Transmission projects often run into local opposition, but that can be turned into support if communities are approached early in the process and even invited to earn money off lines that go through them, according to speakers on an Advanced Energy United webinar Wednesday.

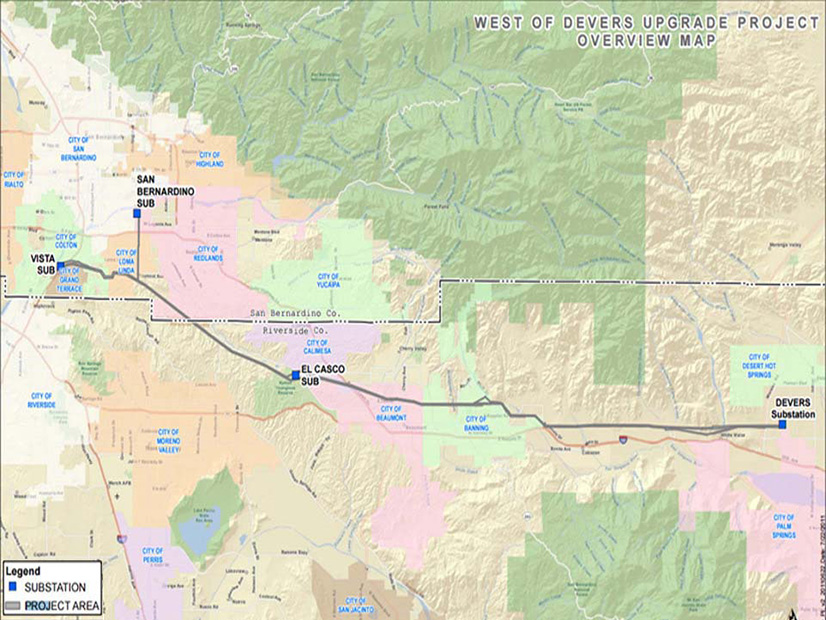

One example of a transmission project working with a local community was Southern California Edison’s West of Devers project that sought to upgrade a 50-year-old transmission line to bring in more renewable power to SCE’s customers from the east, said former FERC Commissioner Suedeen Kelly, now a partner at Jenner & Block.

The old transmission line went through tribal land of the Morongo Band of Mission Indians, who live near Palm Springs. The old line had a right of way that expired early in the last decade, which the utility needed to expand in terms of its geographic footprint, as well to upgrade the line from 230 kV to 345 kV.

“Now, the interesting thing is that there is no power of eminent domain on tribal lands,” Kelly said. “This was a situation that started with some tension. The tribe had only been paid a minimal amount of money — less than $100/year for this old right of way. And they didn’t feel at all warm and fuzzy about extending the right of way, either in time or in width.”

SCE reached out to tribal leadership to come to a mutually beneficial agreement, which wound up with the tribe becoming its partner in the development, investing $400 million for half of the project and earning returns on it through a new company called Morongo Transmission.

“The benefits were extraordinary to this joint venture,” Kelly said. “If Morongo had not agreed to the right of way, it would have meant rerouting the transmission line around the reservation at a cost of over $500 million. And it would have taken eight more years to get this transmission line between California and Arizona into place.”

The deal helped the line move forward, benefiting SCE’s customers and helping to implement California’s policy of growing renewable energy, while turning what had been a combative relationship into a collaborative partnership, she added.

FERC approved Morongo Transmission to collect annual revenue requirements for 30 years to recoup its investment, and those profits will go into tribal coffers to benefit the community, said Kelly. The deal benefited SCE’s other ratepayers because it avoided the costly upgrades and delays of going around their land.

The SCE-Morongo collaboration was based on a model pioneered by Citizens Energy, which was founded by Joseph P. Kennedy II in 1979. The company initially worked on similar deals in the oil industry, which helped low-income customers in New England get cheaper heating fuel. But the firm also has worked in the electric industry for decades and is working on transmission projects in California and the Northeast, said its managing director, Joseph P. Kennedy III. (The father and son are both former members of Congress, and are the son and grandson, respectively, of Robert F. Kennedy.)

“The company was founded over 40 years ago, by my dad, as an innovative nonprofit to help low-income families meet their basic needs,” Kennedy III said. “It is an interesting structure. It’s a nonprofit parent that sits on top of a bunch of different for-profit entities. So, we run it like a proper business: The revenues flow up to a nonprofit parent, and we give a large portion of our revenues away every year [to] communities that we serve to try to meet their needs.”

Citizens’ transmission model carves out part of a utility’s, or merchant developer’s, transmission investment to use for nonprofits that benefit communities impacted by the project. The firm will invest 10 to 20% of a project and use the rate-of-return to cover its costs and turn the rest of the returns over to local uses. The first project for which Citizens used that model was San Diego Gas & Electric’s Sunrise Powerlink, which brought renewable energy from the Imperial Valley to the utility’s territory.

“We now use the profits off of that line, our portion of the profits, to help finance the largest low-income community solar program in the nation,” Kennedy III said, “where 12,000 low-income households in the Imperial Valley get discount solar electricity every year for the next 20-plus years.”

The model holds promise to build the transmission needed to integrate the clean energy while giving local communities that host the infrastructure some tangible benefits, he said.

“It also sets you up not just for the engagement in this project, but it builds those relationships to talk about the next one, and to talk about what the needs of the community are,” Kennedy III said. “And to see, how in fact, we can help leverage this environmental and economic transformation that needs to happen from a national level and a global level to local benefit.”