The money may not be much by federal government standards, but the $60 million the U.S. Department of Energy may award to three pilot projects demonstrating enhanced geothermal drilling technologies could have a major impact on helping the U.S. decarbonize its grid by 2035.

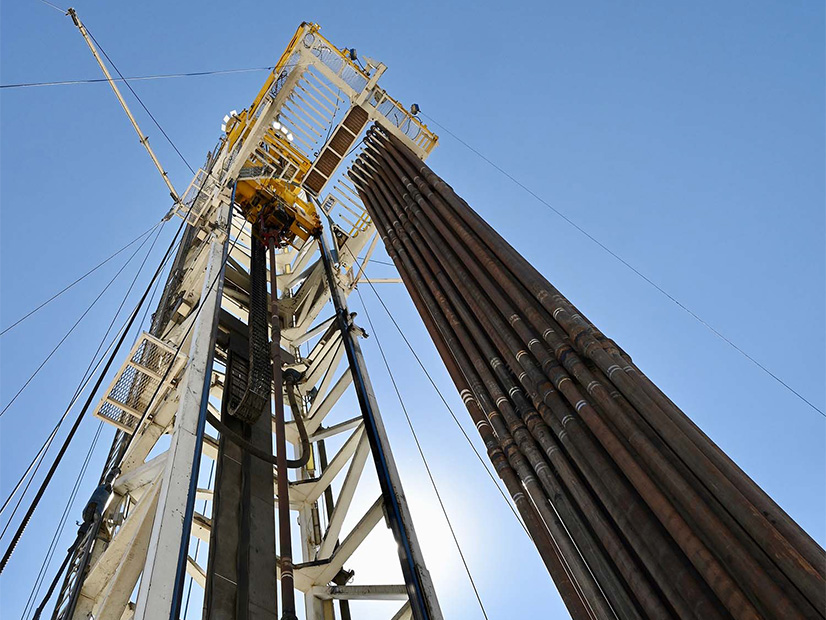

Traditional geothermal wells are located over existing underground sources of heated brine or other fluids, which produce steam to run turbines. Enhanced geothermal seeks to tap previously inaccessible geothermal heat even deeper underground by injecting fluids, in some cases using drilling techniques and equipment from the oil and gas industry.

A recent DOE analysis estimates that if fully developed, enhanced geothermal systems (EGS) could provide up to 90 GW “of firm, flexible power to the U.S. grid by 2050,” according to the funding announcement released Feb. 13.

The three projects will be located in Northern California, Utah and on a volcano in Oregon.

“These projects will help us advance geothermal power … into regions of the country where this renewable resource has never before been used,” Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm said in the announcement. Funded by the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), “these pilot demonstrations will help us realize the full potential of the heat beneath our feet to reduce carbon emissions, create domestic jobs and deliver clean, cost-effective, reliable energy to Americans nationwide.”

The demonstration projects will also support DOE’s Enhanced Geothermal Earthshot, which is targeting a 90% cut in EGS drilling costs by 2035.

The DOE announcement does not specify how the $60 million would be divided between the three projects, nor any requirements for projects to match the IIJA dollars with private investments. The three projects will now enter negotiations with the department to finalize the terms of the funding.

The Projects

Chevron New Energies leads the list of awardees with a project that will “use innovative drilling and stimulation techniques” to access geothermal energy near an existing geothermal facility in Sonoma County in Northern California.

While neither DOE nor Chevron have provided further details, an article in the North Bay Business Journal suggests that the demonstration project is being developed with Sonoma Clean Power, a community-choice aggregation utility. Located near the Geysers geothermal complex, which has been in operation since 1960, the project could produce up to 20 GW of power to start and expand to 200 GW, according to the report.

Chevron’s goal is to “reduce well costs and increase well productivity,” the company said in an email to NetZero Insider. “This effort is essential to closing technology and cost gaps to achieve the DOE’s goals for enhanced geothermal systems. Project learnings will be used to improve the effectiveness of novel geothermal technologies, reduce the costs of implementation and advance widespread commercial deployment of EGS across the United States.”

Headquartered in Houston, Fervo Energy will use its DOE grant to drill three wells at a site in Utah “with no existing commercial geothermal power production.” The goal is for each of the wells to produce 8 MW.

According to information on the company’s website, Fervo also uses oil and gas technologies, such as “precision directional drilling technology to drill horizontally in geothermal reservoirs.” The company’s Cape Station well, one of the three receiving DOE funding, has already been able to cut drilling times 70% year-over-year and slash costs by about 50%, according to a press release issued Feb. 12.

“These results substantiate the rapid learning underway in the geothermal industry and signal readiness for continued commercialization,” the company announcement said.

The final project receiving IIJA funds is a first-of-its-kind pilot to be located at the Newberry Volcano in Oregon, demonstrating a technology for “super-hot” EGS, reaching temperatures of 375 degrees Celsius, or more than 700 degrees Fahrenheit.

DOE identifies Mazama Energy as the project lead, but a website and online research papers indicate that the concept of developing a super-hot EGS project at the Newberry Volcano has been discussed since 2010. Located in the Newberry National Volcanic Monument in Central Oregon, the volcano last erupted more than 1,300 years ago, but is still considered active by the U.S. Geological Survey.

A 2020 paper on the project notes that “super-hot dry rock (more than 375 C) is much more energy dense than conventional hot dry rock (less than 225 C), and production of supercritical EGS steam would represent an energy breakthrough. A super-hot EGS well would produce five to 10 times as much electricity as other well types.”

The ‘Invisible’ Renewable

As increasing amounts of variable solar and wind energy come onto the grid, EGS could emerge as a potential source of zero-carbon, baseload power, and one with a broad geographic footprint, said Bryant Jones, executive director of Geothermal Rising, a North American industry trade association.

“Geothermal is everywhere,” Jones said. “Some places you might use one type of geothermal technology versus another. You might use EGS in one place, geothermal heat pumps in another.”

It also has a smaller carbon and environmental footprint than other renewable technologies. As “the invisible energy technology,” it is often overlooked by policymakers and the general public, Jones said.

While EGS may borrow oil and gas drilling technologies, it is using them in different ways, he said. “Geothermal fracking does not use … chemicals in the way that oil and gas does.” Oil and gas use chemicals to extract materials out of the ground; EGS is only tapping “hot water to spin a turbine and create electricity or to use heat for an industrial purpose,” Jones said.

“You’re using a geothermal aquifer that’s … often thousands of feet beneath any agriculture or drinking water aquifers,” he said.

Looking ahead, Jones sees the DOE pilot projects demonstrating “that geothermal is cost competitive with all other energy power generating technologies … [with] a price point that will inspire or encourage private investment.”

The current awards are the first round of the IIJA funding for EGS demonstration projects, according to DOE. A second round, yet to be announced, will provide support for East Coast projects.