More than 11,000 MW of battery storage resources are now deployed across CAISO’s grid — with much more on the way.

But how much are California’s batteries really displacing gas-fired generation?

Answering that question isn’t easy, according to CAISO staff and other electric industry experts, who say that while batteries are having a notable impact, several factors — including weather conditions and the behavior of storage resources — complicate the narrative that they are displacing gas on the grid.

“You can confidently say that batteries are displacing the need for natural gas energy production, but — and this is a large ‘but’ — batteries are not displacing the need for natural gas capacity just yet,” Carrie Bentley, CEO and co-founder of Gridwell Consulting, told RTO Insider.

Battery buildout has coincided with the need for additional capacity to ensure reliability, especially as 2024 saw another record-breaking year for high temperatures. Reliability modeling indicates that most, if not all, of the gas fleet is still needed, as well as all the current and planned batteries for the next decade, Bentley added.

“This is not as bleak for the environment as it sounds because batteries are displacing the gas fleet energy production and therefore lowering natural gas emissions,” Bentley said.

No ‘One-for-one Displacement’

Energy storage capacity on the CAISO grid grew from under 500 MW in the summer of 2020 to 11,200 MW as of June 2024, representing a “significant” pace of deployment, Sergio Dueñas Melendez, the ISO’s battery storage sector manager, said in an interview with RTO Insider.

CAISO’s Western Energy Imbalance Market includes an additional 3,500 MW of battery capacity, according to a July 2024 report from the ISO’s Department of Market Monitoring.

While Dueñas Melendez noted that the ISO does not currently have a metric to determine whether batteries have displaced the need for gas on California’s grid, the addition of energy storage has had an obvious impact.

“Now that we have way more batteries, we definitely are seeing that batteries are charging in periods of high solar radiation and discharging as the sun starts to set into the afternoon peak and the peak hours,” Dueñas Melendez said. “Earlier this year, the ISO broke a record of peak battery discharge, with over 7,000 MW in a given five-minute interval of battery discharge.”

Pointing to data from the DMM showing the change in hourly generation by fuel type between 2022 and 2023, “you can see how gas, on average, especially in certain hours, has reduced its output, and batteries have increased their output,” CAISO COO Mark Rothleder told RTO Insider.

But the behavior of batteries complicates making an exact calculation of the level of displacement.

“You will not see a one-for-one displacement because a four-hour battery is not going to perfectly displace a dispatchable gas resource over the day,” Rothleder said. “The capability of the batteries over four hours versus being able to ramp day-over-day and intraday of the gas fleet doesn’t allow you, at this point, to fully replace the gas fleet with batteries. But there is certainly energy displacement.”

Guillermo Bautista Alderete, CAISO’s director of market analysis and forecasting, added that a one-to-one replacement of gas with storage supply cannot be assumed because of the dozens of storage and gas resources with varying costs and locations. He also noted that, given the level of storage in the system, those resources can also be displacing of other types of supply, not just gas — the exact value of which is also unclear.

“Since the market determines the optimal dispatch of all resources based on their bid costs and attributes, it can’t precisely track in isolation the specific volumes of gas supply displaced by storage resources compared to other supply types,” Bautista Alderete said in an email. “Changes in the level of gas supply dispatched at any given time depend on various factors, including the relative bid costs of different technologies, demand levels, hydro conditions, renewable production, resource availability, gas prices, seasonal conditions, transmission congestion and broader supply/demand conditions in the WEIM that influence the level of transfers.”

Weather Impacts

The degree to which batteries displace gas can also depend on prevailing weather conditions.

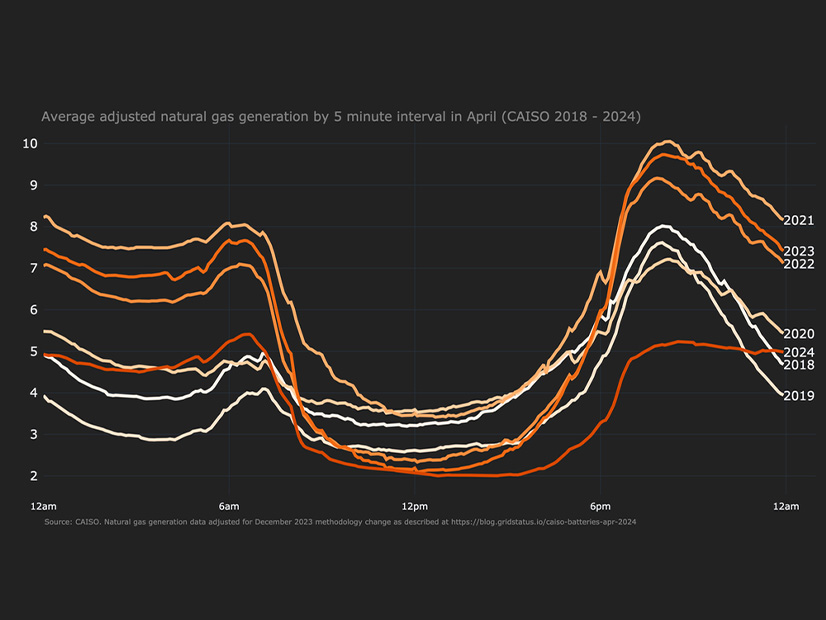

A May 2024 blog post from energy data provider Grid Status contended that battery storage was the “standout performer” in CAISO last spring, saying that “batteries are displacing natural gas when solar generation is ramping up and down each day in CAISO.”

But the report only cited data from April, which does not show the full picture, according to Bentley.

“April is not indicative of the annual trend, because what’s happening in April is you have very low demand, but it’s starting to get sunny,” she said. “This is basically the perfect time for batteries.”

California successively broke records for summer heat in 2023 and 2024, which drove high — although not record —peak loads. While natural gas usage remained high, it decreased as batteries grew, even as peak demand increased.

According to CAISO data, the ISO’s 2023 peak demand occurred on Aug. 16 at 44,534 MW. In the early evening hours, as solar ramped down, natural gas peaked at 26,490 MW, with batteries dispatching at 927 MW. As the evening progressed, batteries ramped up, peaking at nearly 3,000 MW, while natural gas ramped down to just over 25,000 MW.

The 2024 peak of 48,353 MW occurred on Sept. 5. As solar ramped down in the early evening hours, both gas and batteries ramped up well into the night. Despite the increased net demand and record-breaking heat compared with the prior year, the natural gas peak topped out at just over 23,000 MW, while battery output rose to over 6,000 MW — reflecting a seasonal pattern that resulted in an “uneventful” summer despite periods of extreme heat, according to CAISO. (See Batteries, Energy Transfers Support ‘Uneventful’ Summer in West.)

When considering different periods and associated trends, all system conditions must be considered, Bautista Alderete added.

“The supply mix will inherently be lower across various technologies to meet the demand on a spring day with a peak of 30,000 MW, compared to a much higher supply mix needed to meet the demand on a summer day with a peak of 50,000 MW,” Bautista Alderete said. “Naturally, a higher level of supply is required to meet peak demand during the summer.”

The growth of battery energy storage in tandem with the decrease of natural gas is expected to continue. The California Energy Commission projected the need for 52,000 MW of battery energy storage by 2045, a goal that CAISO’s Dueñas Melendez said the state is on track to meet.

“We have more in the queue than that,” Dueñas Melendez said. “The real challenge — across the different agencies, for developers and for the ISO — is to be able to manage that influx in an orderly way to get to that goal.”