The U.S. Department of Energy has slashed the list of 10 potential National Interest Electric Transmission Corridors it released in May to just three much narrower corridors in the third phase of its designation process, the department announced Dec. 16.

Established under the Federal Power Act, NIETCs are geographically defined areas in which the secretary of energy finds “present or expected transmission capacity constraints or congestion that adversely affects consumers,” according to the announcement published in the Federal Register. Transmission projects located within a NIETC are eligible for special DOE financing and FERC permitting processes aimed at accelerating development and construction.

DOE set out a four-step process for NIETC designations in December 2023, including an initial information-gathering phase to help identify potential NIETCs, followed by the release of the preliminary list of 10 possible corridors in May. (See On the Road to NIETCs, DOE Releases Preliminary List of 10 Tx Corridors.)

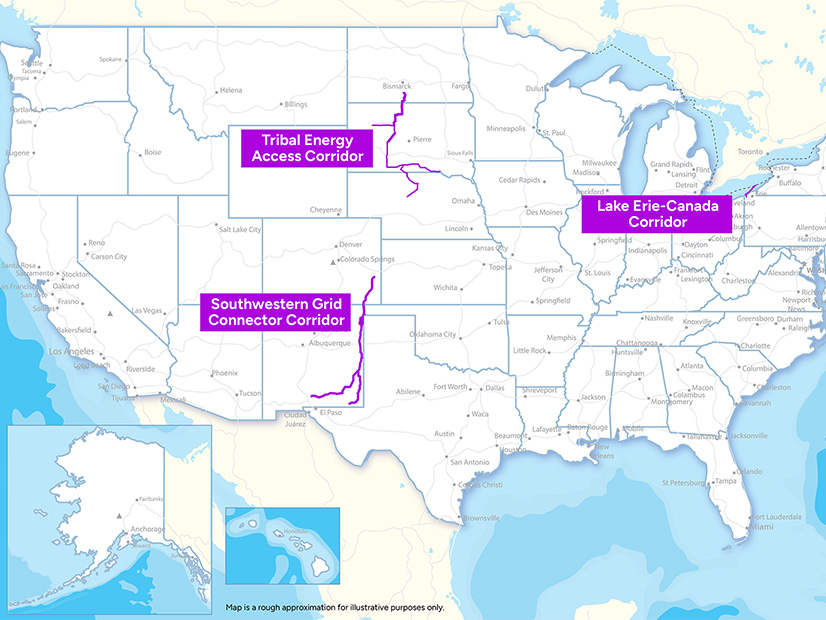

The three proposed NIETCs selected in Phase 3 are:

-

- the Lake Erie-Canada Corridor, including parts of Lake Erie and Pennsylvania;

- the Southwestern Grid Connector Corridor, including parts of Colorado, New Mexico and a small portion of western Oklahoma; and

- the Tribal Energy Access Corridor, including central parts of North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska and five tribal reservations.

According to DOE, its decisions on these three corridors were based on its own analysis and the public comments it received during the first two phases of the process, as well as priorities set in the department’s National Transmission Needs Study released in October 2023.

“Transmission development in these areas is critical to address transmission needs … unmet through existing planning processes,” DOE said. All three corridors also have one or more transmission projects under development, which DOE sees having near-term impacts on easing grid congestion, helping to put more renewable energy online and cutting consumer costs.

For example, the Lake Erie-Canada Corridor is a slimmed-down version of the Mid-Atlantic-Canada corridor on the Phase 2 list of 10 potential NIETCs. The Phase 3 version contains a smaller area in Pennsylvania and a larger area in Lake Erie. NextEra Energy Transmission’s Lake Erie Connector project, a 73-mile underwater line, could be located in the corridor, allowing for bidirectional energy flows between Pennsylvania and Ontario.

While the project is still in the early phases of development, a transmission corridor with that kind of HVDC line would increase capacity for clean energy integration on the grid, as well as support resource adequacy in PJM via the connection with Canada, according to DOE.

The Tribal Energy Access Corridor is a similarly “refined” version of DOE’s Phase 2 Northern Plains potential NIETC, with most of the corridor running along existing rights of ways and connecting several tribal reservations to existing or planned HVDCs.

The corridor includes parts of the Dakotas, Nebraska, the Cheyenne River Reservation, Pine Ridge Reservation, Rosebud Indian Reservation, Standing Rock Reservation and Yankton Reservation.

NIETC designation here could help the Transmission and Renewables Interstate Bulk Electric Supply (TRIBES) HVDC project being developed by the Western Area Power Administration and other tribal and regional stakeholders, as well as relieving congestion and preparing for future demand growth. Nebraska, for example, is becoming a hub for data center development as part of a new “Silicon Prairie.”

While highlighting these projects, DOE noted that “NIETC designation is not a route determination for any particular transmission project, nor is it an endorsement of one or more transmission solutions.”

Why These, not Those?

Declining to comment on specific corridors, Dylan Reed, senior adviser for external affairs in DOE’s Grid Deployment Office, listed a number of reasons for the exclusion of the other Phase 2 potential NIETCs.

“NIETC designation can disrupt effective transmission planning or ongoing transmission project development in the region. That was one consideration,” Reed told RTO Insider.

“[No. 2] … there appeared to be limited [ability for] a NIETC designation to further transmission in the near term in that area. In some cases, we lacked sufficient information to be able to narrow the boundaries to facilitate timely designation,” he said.

Beyond prioritizing NIETCs that might meet shorter-term needs, DOE pointed to its own limitations of staffing and time for taking Phase 3 NIETCs to a final designation in Phase 4. The department is opening a 60-day comment period, which will include three webinars, one on each of the proposed NIETCs. The comment period will close Feb. 14, 2025.

Another key component of Phase 3 is determining whether the potential corridors will need a full environmental review under the National Environmental Policy Act. A NEPA review for each corridor could be required if DOE determines that “NIETC designation is a major federal action significantly affecting the quality of the human environment,” according to the announcement.

The department is also asking for additional input on other meetings or community engagement activities it should plan as part of its environmental reviews.

A full NEPA review could take two years, so Reed would not speculate on when final NIETC designations might be made. He also declined to speculate on what impacts, if any, the incoming administration of President-elect Donald Trump might have on the NIETC process.

But DOE said its decision not to move the other Phase 2 projects forward does not mean those areas do not have transmission needs. “Rather, DOE is exercising its discretion to focus on other potential NIETCs at this time and may in the future revisit these or other areas through the opening of a new designation process,” it said.

NIETC vs. NIMBY

Even before it was cut from the list, the Delta-Plains corridor drew strong political and public opposition within Oklahoma over the possibility of eminent domain acquisition of private lands.

As originally proposed, the corridor would have stretched 645 miles from Little Rock, Ark., through the Oklahoma Panhandle, with an 18-mile right of way in some portions.

“I won’t let anyone steamroll Oklahomans or their private property rights,” Gov. Kevin Stitt (R) posted on X. “The feds don’t get to just come here and claim eminent domain for a green energy project that nobody wants.”

Attorney General Gentner Drummond (R) sent a letter to U.S. Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm calling the corridor “classic federal overreach” and pledged to protect private property rights.

DOE gave Oklahoma’s leadership advance notice on Dec. 13 that the Delta-Plains corridor would not be moving forward.

With or without a NIETC, the region does not lack for proposed transmission projects that could run into similar NIMBYism. The Southwestern Grid Connector corridor will graze the western edge of Oklahoma’s state line. DOE notes two projects in development in the potential NIETC: the Heartland Spirit Connector project by NextEra Energy Transmission, and the Southline Phase 3 project by Grid United.

Invenergy also has proposed the Cimarron Link to unlock access to the Oklahoma Panhandle’s “inexhaustible wind energy.”

SPP, which operates the grid in Oklahoma, has approved several large projects in the state as part of its 2024 Integrated Transmission Planning assessment. (See SPP Board Approves $7.65B ITP, Delays Contentious Issue.)